0._A_Second_Modernis..

advertisement

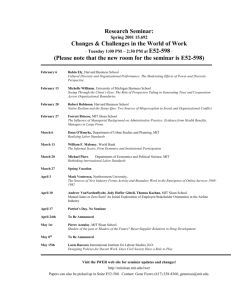

A Second Modernism MIT and Architecture in the PostWar Editor: Arindam Dutta The objective of this book is to examine the so-called “techno-social” turn in architectural studies in the immediate aftermath of WWII until the 1980s. Architectural thought in this period is marked strongly by linguistic, behavioral, computational, mediatic, probabilistic, generative and cybernetic paradigms. In recent years, architectural historians of the postwar, focusing their attention towards these paradigms, have increasingly encountered the influential role of MIT’s School of Architecture and Planning in this postwar shift, one that parallels its central influence in the technological world as well. Indeed, the School in this period is distinctly characterized by a shift away from architectural formalism, exhibiting instead a preoccupation with “research” housed in pseudo-laboratory-like cells, each reflecting the interests of particular group of personnel. A series of micro-institutions, harvesting both opportunities within MIT’s particular research dispensation as well as national and international arenas of expertise and funding, set up home at the Institute in this period, becoming landmark edifices in their often disparate theaters of activity: the Special Program for Urban and Regional Studies (SPURS), the Harvard-MIT Joint Center for Urban Studies, the Center for Advanced Visual Studies (CAVS), the History Theory Criticism (HTC) Program, the Laboratory of Architecture and Planning, the Environmental Design Program, the Architecture Machine Group and the Media Lab are all units that emerged from this “research”-based investment into architecture. A distinctive set of experts also emerged, never quite central to the architectural field, but luminaries nonetheless at its penumbra: William Wurster, Gyorgy Kepes, Kevin Lynch, John Habraken, Nicholas Negroponte. Design training at MIT also reflected these forces, focusing strongly on broad urban and behavioral modeling practices on the one hand, and techno-social engineering on Dutta, (Provisional) Introduction 0. 1 the other. This book attempts to marshal the work of scholars already working on these complex interactions into a single volume, using the MIT archive as a guiding focus. This shift towards complexity –based research models was not an intuitive shift that suddenly flowered simultaneously in the minds of architects or planners. Quite to the contrary, they emerged out of concrete attempts to mine particular institutional and funding arrangements of the American postwar, both in the sciences and the social sciences, the two major fronts of national zeal. In 1945, the outlines of the seminal report presented to the Truman administration, Science: The Endless Frontier, laid out a dichotomy for advanced university research in the United States until the 1980s that would be definitive not for scientific research alone. The dichotomy was an older one, between “basic” and “applied” research, but in the context of the American postwar this distinction drew not so much from epistemological concerns as from a particular set of agreements made between different factions. The first was the military’s own appreciation of the continued need to pursue scientific research at scales commensurate with wartime intensities, given the widespread realization that the war had been fought less on conventional grounds than on strategies drawn from technological advantage. The second faction was that of research personnel directly interested in military applications, these including elements in private industry. The third – and most important – was the consortium created by major research universities, led by MIT’s Vannevar Bush and Harvard’s James Conant, to garner moneys made available by government for scientific research to significantly expand their scope of operations. Scholarship on American research universities in the postwar has pointed to a peculiar confluence of interests that defined the research agenda in this period. The 1945 Science report, made by Bush at the helm of the Office of Scientific Research and Development, put inordinate emphasis on the primacy of “basic” science as against the government’s interest in applications-led research. Bush and Conant’s emphasis on basic science was in fact the flip-side of a political attitude, comprising a strong belief on small government on the one hand and the individual autonomy of the scientist on the other. That this lurch for autonomy found a paradoxical audience in what could otherwise be considered the proverbial belly of the big governmental beast was due a particular attitude on the part of government itself: that any applied research required a strong background in basic science initiatives and training before it could bear fruit. This at least was the rationale offered again and again to Dutta, (Provisional) Introduction 0. 2 Congress for the various requisitions of the first two decades after the Bush report. The post-war research apparatus thus crucially sat on a paradoxical platform: a belief system vested in institutional autonomy and non-interference from government in setting research agendas was thus signally subsidized and expanded by the growth of governmental investment into scientific research, tentatively at a remove. (Needless to say, this tenuous paradox lost its plausibility with the neoliberal turn in the 1980s. When the votaries of small government arrived at the center of American government, this liberal dispensation towards basic science was summarily removed, crucially depriving American basic science of key sources of public funding. Nixon’s infamous “enemies list” comprising the Rad Lab’s Jerome Wiesner and Noam Chomsky being an early case in point. The strings of purses made available with no strings attached were closed tight again.) It also goes without saying that the development of American social sciences in this period were significantly aligned with government interests, even when funded by private foundation grants, since these in turn themselves coordinated their national and international objectives with those of the administration and the State department. MIT’s strong suit in these areas - linguistics, sociology, media sciences, cybernetics, political science, economics – draws significantly from this dual imperative. Indeed, this paradoxical tableau goes much towards explaining why research universities in the American postwar were both strong locations of governmental intervention and the often paid-up “counter-cultural” ethos that vilified this intervention as elements of the “military-industrial complex.” On the other hand, even as various kinds of social critics from Lewis Mumford to Langdon Winner declaimed the exceeding technological determinism of everyday live, technologists turned more and more to different kinds of social sites as the basis for the ethical reprieve of science: the Odyssean travel of the microwave oven from military radar being the vaunted case in point. The “aesthetic” fronts of art and architectural practice, in the face of an exponentially expanding field of institutional research in these particular knowledge fields, were left to make of it what they would, and some would. Thus, even before the transition of pedagogical models from classicist to modern, from Beaux-Arts to the Bauhaus – the effect a new wartime European diaspora – had been significantly resolved, one sees the imperative of the second, “systems”-based, revolution superimposed onto the first one. A second Dutta, (Provisional) Introduction 0. 3 avant-garde, this time drawn more from the positivist legates out of Vienna, Prague and Cambridge, England rather than Paris, Berlin or Dessau also took hold in the American scene. An entire dispensation of émigré thought in this period, from Bernard Rudofsky to Gyorgy Kepes and Eero Saarinen, not to rule out the young Peter Eisenman (via Cambridge), as well as the homegrown variants – Louis Kahn, Arthur Drexler, the Eames, Christopher Alexander – can be listed in a series whose work could be described as much as a counter-modernism, operating at a step away from the late-CIAM deliberations, invested instead in the “scientific” implications of their trade. Each affects a “research” outlook to the outcomes of their art, boldly projecting broad social and institutional transformations at their core, banded often with a strong anti-aesthetic impetus. MIT would emerge in this time as a key center for this counter-modernism. Studio teaching in this period significantly reflects – in consonance with its research units – an investment into complexity and linguistic paradigms, focusing on the mechanisms behind architectural decision-making rather than the nuances of the architectural object per se. The interest in catechizing the rationale behind the decisions of a profession in order to expand its “expertise” – as opposed to conventional virtuousity – is what we can call the determinant of a “Second Modernism”: the tentative title for this book. All of MIT’s grandees, Kepes, Lynch, Rodwin, Habraken, Negroponte, William J. Mitchell, and even the historians Hank Millon and Stanford Anderson in their first phase – can be described as members of this second template. It is worth nothing that even the inceptors of its historians’, the History Theory Criticism (HTC) Program, began with a similar sociological investment, with the strong influence of certain computation and Popperian paradigms. The road between Cambridge, MA and Washington, DC, so fruitfully traveled by MIT’s scientists, would also be traversed equally by MIT’s architectural historians with the establishment of the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts at the National Gallery of Art (readers would do well to note the similarity with Kepes’ CAVS) in 1979. Schools of architecture have often commemorated themselves in celebratory histories. The undertaking in this book is somewhat different. Although it uses the MIT archive as its central basis, it attempts to capture what increasingly appears in current scholarship as a cogent "phase" or "moment" in the history of postwar American architecture prior to the onset of postmodernism. Prior to the 1980s, both curricular and research agendas in schools Dutta, (Provisional) Introduction 0. 4 of architecture in the US comprised strong components of positivist sociology, systems thinking, as well as heavy borrowings from (little acknowledged) epistemological models from the field of linguistics. (One only needs to think back to widely-bandied terms like "urban morphology," "figure-ground," "architectural grammar," to remember this borrowing.) These epistemological movements between fields speak as much to the hybrid constitution of a field such as architecture as the attempt by its purveyors and "experts" to acquire a certain epistemic authority in the institutional matrices of the post-WWII period. In the context of the 1960s and 1970s, as wartime modes of organization morphed into expanded interventions into peacetime life, significantly empowering the apparatuses of demand-management, nowhere was this "techno-social" managerialism more evident than in a "defense institute" such as MIT. Likewise, as Vietnam cast a pall on this technocratic ebullience, nowhere was both epistemic mode and epistemic authority more put into question as at the institute -- both Daper and Chomsky were to become legends within two entirely opposed factions. Unto the nineteen-eighties, therefore, the history of architecture and urban planning at MIT encapsulates something like the very core of transitions in American social and technological life. At the same time, it is because of the specific embedment of architecture within the technological institute that in the nineteen-eighties, the epistemic paradigm of the school would face its severest crisis: if before WWII, architecture at MIT remained a truncated field because of its inability to get rid of its BeauxArts heritage and fully embrace modernism, in the context of the 1980s, as the postwar consensus fell into disuse and disrepute, MIT architects appear unable to figure out (manifesting an overt hostility) what to do with postmodernism. As its sister institutions on the east coast -- the Rowe acolytes, the Graves and Stern hangers-on, the AA infusion, the Tschumi deconstructivists, and so on -- churned their way through various curricular transformations, a peculiar loss of conviction wormed its way into MIT architecture: for twenty years the design faculty did (could) not tenure a single new faculty. Using 1945 and 1980 as its two bookends, therefore, this book attempts to capture a "conjuncture" in the history of American architecture when certain external forms of epistemic authority appeared to offer an internal cohesiveness to the discipline. (Indeed, at Berkeley, where "architecture" was morphed into the more catholic heading of "environmental design," the leading edge of teaching was defined not by architects but by sociologists, anthropologists and the like.) In recent years, the "history of science" and Dutta, (Provisional) Introduction 0. 5 "science and technology studies" paradigms have strongly affected emergent research work in the field of architectural historiography, yet another moment in paradigmatic crossfertilization and -legitimization. Inasmuch as this book attempts to recuperate the above conjuncture amongst technological, aesthetic and architectural thought, it is also an attempt to use the MIT archive to curate and collate the disparate strands of a burgeoning historiographic approach. I have made particular efforts to source the work of younger scholars -- recent Ph.D.s or junior faculty -- whose ongoing work is particularly close to the issues and events in question. The general tendency amongst this group appears to be to sift out, behind the extravagant claims of technological competence and epistemic authority, certain institutional or material limits or constraints that figure or determine social relationships within the field into particular cohorts or networks. Behind the grandiose, overarching, claims of the discipline, what is revealed therein is a great deal of uncertainty about its constitution. Indeed, it is precisely in confronting this radical uncertainty that books, journals, objects, buildings, technologies are produced, not so much as "solution" but rather creating the anthropological profile through which "expertise" can be performed, attributed, realized. This is particularly true of MIT, on the one hand the founding institution of architectural teaching in the United States, and on the other, on many grounds perhaps a place where actors within the architectural school in the post-WWII era appeared to go furthest from a "proper" conception of architecture, producing, in the bargain, a host of unanticipated frameworks: the Media Lab, CAVS, HTC, and so on. As mentioned before, a slew of historians have already begun to traverse this muchtrafficked terrain of the arts and sciences in the American postwar, one that points increasingly to MIT’s nodal role in that traffic. Nonetheless, while MIT looms large on certain histories of architecture, no research work exists yet that appraises these relationships from an institutional viewpoint. How did institutional policies, politics and pedagogy transform themselves to put themselves in accord with the exponential growth of institutional power and influence, particularly in fields such as architecture, urbanism and arts, which conventionally held little promise for profit either in the way of military or commercial products? What new kinds of emphases do we find in the classrooms of the period, in addition to the published polemics of faculty, and how did these emphases reflect broader exigencies of what nineteenth century writers euphemistically described as “establishment”? How were the disparate imperatives of disinterested research, tendentious Dutta, (Provisional) Introduction 0. 6 research and professional training reconciled or superimposed into “architecture” as a portmanteau term? How did aesthetic preoccupations, broadly defined, strike ground in the scientific imaginary, and vice versa? The contributed essays to this volume focus on disparate facets of MIT’s history, drawn from the expertise and particular interests of the contributing authors. The essays envisaged so far focus on a host of issues: the internal dynamics of the departments and the school; hiring and firing patterns; the intellectual context and dissemination of the ideas of figures such as Kepes, Lynch, Wurster, Habraken, Millon; the ideas behind the formation of the various research groups, Architecture Machine Group and the Media Lab, CAVS, HTC, the Harvard-MIT Joint Center; studio teaching in this period; MIT’s affinity for particular sibling institutions, Berkeley and Cambridge, UK; the peculiar affinity of this “techno-social” thought with particular variants of “regionalism” or culturalism; the various consultancy missions to the “Third World”; and so on. The tone of the book will be that of historical critique, which is to say that book will attempt to provide the reader with the critical tools by which to judge the complex determinants of a particular period. The book thus proposed will not only contain polemical essays by the aforementioned authors, but also comprise significant visual and documentary extracts from MIT’s archives. From the standpoint of MIT’s School of Architecture and Urbanism, as it contemplates radical changes in its administration and pedagogy, it is important that these questions be asked in order to highlight its former heyday. Such an in-depth historical study is only fitting for America’s first department of architecture, and it is hoped that the book will be published in 2011 as part of the Institute’s 150-year celebrations to mark that influential beginning. In terms of methodological approach, the book brings together a recent trend towards integration between "Science and Technology Studies" paradigms and architectural history. With the exception of established scholars such as Reinhold Martin, Felicity Scott, Mark Wigley, Antoine Picon, etc., this trend is still nascent, implicit in the work of some recently appointed faculty and doctoral students. In a sense, this work attempts to "capture" that moment, with MIT as the felicitous archive for exploring these insights. To encapsulate this trend: writing on technology in architecture has generally tended to manifest itself into "operative" questions of expressive honesty, historical appropriateness, effects on society, and so on. Only more recently has this "operativity" itself come into focus as an area of Dutta, (Provisional) Introduction 0. 7 scholarly interest, in terms of the history of the personnel, the transfer of epistemological paradigms, the institutional dynamics involved. One implication of this trend is to disaggregate the paradigms from which architecture is said to emerge: exposing rather a play of interests, networks, and incentives towards authority over which a discipline casts its shadow and name. Dutta, (Provisional) Introduction 0. 8