MAR Strategic Plan

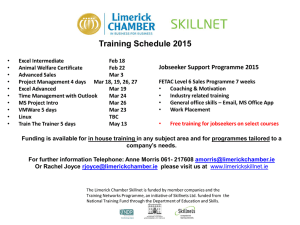

advertisement