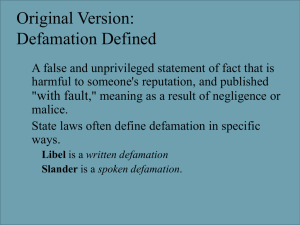

Balancing Reputation Rights and Freedom of Speech

advertisement