Words by Default: the Persian Complex Predicate Construction

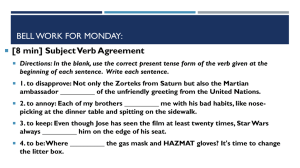

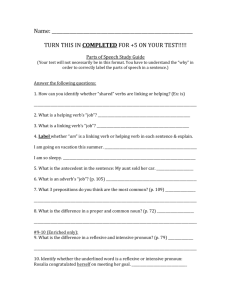

advertisement

2003. Words by default: the Persian Complex Predicate Construction. Elaine Francis and Laura Michaelis (eds.) Mismatch: Form-Function Incongruity and the Architecture of Grammar. CSLI Publications. 83-112. Words by Default: the Persian Complex Predicate Construction1 Adele E. Goldberg University of Illinois 1. Introduction Persian (Farsi) has a large and open-ended set of complex predicates that consist of a non-verbal element, the host, followed by a light verb. Complex predicates (CPs) are of interest in the context of the present volume because they display a mismatch of lexical and phrasal properties: they act in some ways as a single word, and in other ways like more than one word. They form a central part of the grammar of Persian and many other languages, including Hindi, Japanese and Hungarian.2 This paper offers an account in which the Persian CP is treated as a construction represented in the lexicon3. Constructions are pairings of form and meaning that are learned and stored as pieces of linguistic knowledge. The existence of a construction can be established by demonstrating that some aspect of a usage pattern is not strictly predictable from its component parts or from other facts about the language. Productive lexical or phrasal patterns, semi-productive lexical or phrasal patterns, fixed idioms and morphemes are all potential constructions as long as some aspect of their form or function is not strictly predictable. I use the somewhat cumbersome “not strictly predictable” circumlocution instead of saying that the forms are “unpredictable” or “arbitrary.” This is because most forms that are not strictly predictable are neither arbitrary nor totally unpredictable. As Bolinger (1965) reminds us, “what is 95% old is not 100% new.” That is, a given construction often shares a great deal with other constructions that exist in the language; only certain aspects of its form or function are unaccounted for by other constructions. It is clear that not strictly predictable knowledge must be learned and stored as such since it is not predictable from other facts of language. Thus evidence that a word or 1 I would like to thank Elham Sadegholvad, Michael Azarnoosh, Maryam Hafezi, Kathy Soltani and Ali, Parivash and Faizallah Yazdani for their insightful consultant work. I am also grateful to Dick Hudson and Orhan Orgun for reviewing this paper and offering extremely valuable feedback, and to Cedric Boeckx and Farrell Ackerman for helpful comments on an earlier draft. I am sure I will regret any advice I failed to heed; any remaining errors are solely my own. 2 In Persian, there are thousands of conventional complex predicates as compared with roughly a hundred simple verbs (Karimi-Doostan 1997). New and borrowed verbs also appear as complex predicates, e.g., the English borrowing try kardan, “to try.” 3 For reasons that will become clear below, Persian CPs are actually treated as a class of systematically related constructions. The fact that many CPs are idiomatic requires that they be listed as stored instances of the general pattern. pattern is not strictly predictable provides sufficient evidence that the form must be listed as a construction in this expanded version of the lexicon, or what is sometimes called the ‘constructicon.’ At the same time, unpredictability is not a necessary condition for positing a stored construction. There is evidence from psycholinguistic processing that patterns are also stored if they are sufficiently frequent, even when they are fully regular instances of other constructions and thus predictable (e.g., Losiewicz 1992; Bybee 1995). We assume patterns are stored as constructions even when they are fully compositional under these circumstances. The inclusion of these more frequent items brings the present approach in line with usage-based models of grammar (Langacker 1988; Barlow and Kemmer 2000; Bybee 1995; Goldberg 1999). On this view, item-specific knowledge exists alongside generalizations. Thus, morphological stems and productive lexical and phrasal constructions are all treated as the same basic type of entity. This idea is the cornerstone of theories such as Construction Grammar, Cognitive Grammar and HPSG, in which grammar consists of CONSTRUCTIONS which are not strictly predictable form-meaning patterns that are morphological or phrasal (e.g., Fillmore, Kay, & O'Connor 1988; Pullum & Zwicky 1991; Fillmore & Kay 1993; Goldberg 1992, 1995; Jurafsky 1992, Lakoff 1987, Michaelis and Lambrecht 1996; Langacker 1987, 1991; Croft 2002; Pollard & Sag 1987). The fact that the repository of stored entities (the “lexicon”) does not coincide with a list of words in a language is a point that has been made by many others as well (e.g., DiSciullo and Williams 1996; Williams 1994; Marantz 1997; Culicover 1999; Jackendoff 1996; 2002). At the same time, traditional behavioral differences between zero level categories and phrasal categories are recognized on the present account. For example, zero level categories can appear in derivational constructions and cannot be separated syntactically. 4 This fact is important to keep in mind: both zero level words and phrasal patterns are stored together, but the classic distinctions still retain their force. Below it is argued that the categorial status of the CP is a simple verb (V0) by default. Its expression as a verb or as a phrasal entity is determined by independently motivated constructions. Default V0 status accounts for the CP’s zero level properties, including its resistance to separation and its appearance in derivational constructions. V0 status is a default in the sense that it can be overridden if and only if there is another construction in the grammar that specifically overrides it. This proposal is implemented via a default inheritance hierarchy. Hudson (1984; 1990; this volume) motivates the role that default inheritance hierarchies can serve in simultaneously capturing broad-generalizations, partial generalizations, and exceptions (see also Flickinger 1987 and references therein). Broad generalizations exist in the highest levels of the inheritance hierarchy; partial generalizations are captured by lower level representations, and exceptions are specified with their own peculiar properties below one or more of the generalizations. Default inheritance ensures that all To phrase this more traditionally, zero level categories can serve as “input” to derivational processes and are opaque to syntax. 4 2 non-conflicting information is shared between mother and daughter nodes. Conflicting (exceptional) information in the daughter node overrides the inheritance; it is in this sense that the inheritance is default. As noted by Hudson and others, non-linguistic domain knowledge operates on the basis of a default logic. To take an example, consider our understanding of plane-boarding procedures. Almost all airlines have assigned seats and paper boarding passes with the seat assignment on them. When boarding, passengers are boarded from the back of the plane first. This is a broad generalization, and it determines what we know and how we expect to board most familiar or new carriers. Southwest Airlines, on the other hand, does not offer assigned seating, but instead distributes colored plastic boarding passes with ascending numbers, handed out in the order in which passengers check in. Passengers are boarded in groups of thirty and may take any available seat once inside the plane. The more specific knowledge we have about Southwest airlines’ boarding practices overrides the more general knowledge, and determines our expectations about boarding that particular airline. As is the case with linguistic knowledge, exceptions are, to varying degrees, regular as well. The Southwest Airlines boarding procedures share with other airlines many things: all involve some type of boarding pass, all allow pre-boarding of families with young children, and all board passengers in groups. By allowing whatever information is nonconflicting to be inherited, regular aspects of exceptional elements are captured. On the usage-based approach adopted here, more specific knowledge always preempts general knowledge in production, as long as either would satisfy the functional demands of the context equally well. In particular we assume that items lower in the inheritance hierarchy (i.e., the more specific) are preferentially produced over items above them in the hierarchy, when the items share the same semantic and pragmatic constraints. Note that this idea does not predict that speakers must always opt for a word that is maximally specific, universally selecting beagle over dog, for example. This is because beagle and dog are not semantically equivalent: there are contexts where the more general term is more felicitous either because it is more accurate or because the specific information is not relevant (see Murphy and Brownell 1985 on a relevant Gricean explanation for why basic level terms are often preferred over subordinate or superordinate terms). That more specific information should override more general information when the two are functionally equivalent is not a necessary consequence of adopting an inheritance hierarchy, but is one with much precedent (cf. the Elsewhere Condition of Kiparsky 1968, who attributes the generalization to Panini). A hierarchical network of constructions clearly enables the theory to be in principle fully descriptively adequate. Generalizations are captured by higher level constructions in the hierarchy. Moreover, any sort of language-particular idiosyncratic factoid about a language can be captured by a specific enough construction. 3 What imbues a constructional approach with explanatory adequacy is a further desideratum that each construction must be motivated.5 Motivation aims to explain why it is at least possible and at best natural that this particular form-meaning correspondence should exist in a given language.6 Motivation can be provided by factors outside of the language-particular grammar, for example, by appeal to constraints on acquisition, principles of grammaticalization, discourse demands, iconic principles or general principles of processing or categorization. Alternatively, motivation may come from within the grammar. For example, the motivation for one construction having the form it does may come from the inheritance hierarchy itself, insofar as the form is inherited by a construction higher in the hierarchy. Motivation is distinct from prediction: recognizing the motivation for a construction does not entail that the construction must exist in that language or in any language. It simply explains why the construction “makes sense” or is natural (cf. Haiman 1985; Lakoff 1987; Goldberg 1995). To return to the airline example, the general boarding procedures are motivated by the need to get passengers on board in an orderly fashion while respecting passengers’ desire to sit in particular seats. The boarding practices of Southwest airlines are also motivated; Southwest is a low-budget airline specializing in short flights. Priority is given to boarding passengers as quickly as possible. Less priority goes to ensuring that each passenger receives his preferred seat. At the same time that both boarding practices are motivated, neither boarding practise had to be exactly the way it is. The facts are not strictly predictable. Many other regional airlines operate like national carriers and not like Southwest. And it is conceivable that the national carriers could have all operated like Southwest instead of issuing seat assignments. Still, the existing facts are clearly motivated by their function; understanding the function “makes sense” of the procedures, or explains why they are natural. The constructions posited to account for the Persian data are each motivated independently, and are claimed to be typologically natural; however, identical constructions clearly do not exist in every language: it is not claimed that they are universal or that they are innate. Instead it is assumed that they are learned from the positive input learners receive.7 In the present paper, an account of Persian complex predicates involving a default inheritance hierarchy is proposed, and compared with alternative accounts, including Goldberg (1996), which had proposed a ranked constraint analysis of a subset of the data discussed here, using the formalism of OT; it is argued that the DI analysis is preferable on empirical and theoretical grounds. 5 One systematic exception is that the particular phonological forms that a language chooses to convey particular concepts need not be motivated but generally are truly arbitrary (Saussure 1916). 6 An account that fully motivates a given construction is ultimately responsible for demonstrating how the construction came to exist and how it can be learned by new generations of speakers. We do not aim to tackle this more stringent goal in the present paper. 7 See Goldberg (1998) and Goldberg, Sethuraman and Casenhiser (to appear) for an analysis of how semantic aspects of constructions may emerge from the input via a general process of categorization. 4 2. Identifying CPs in Persian Complex predicate is used here to refer to host+light verb combinations in which the host appears in bare form, without plural or definite marking. In finite sentences with simple verbs, primary stress is placed on the main verb. But in finite sentences with CPs, primary stress falls on the host instead. (1) Ali mard-râ ZAD(simple verb) Ali man-acc hit.1.sg Ali hit the man. (2) Ali bâ Babak HARF zad (complex predicate) Ali with Babak word hit Ali talked with Babak. Thus the stress facts treat the CP as a single zero level verb (see Lambrecht & Michaelis 1998 for discussion of principles of sentence accent placement). Additional evidence argues that the CPs act as simple lexical items: they may differ from their simple verb counterparts in argument structure properties, they undergo derivational processes that are typically restricted to applying to zero level categories, and they resist separation, for example, by adverbs and by arguments. The present discussion focuses on combinations that have been classified as “inseparable complex predicates” in that the host cannot appear with a determiner (Karimi-Doostan 1997).8 These so-called inseparable complex predicates are in fact separable under certain conditions. The ability to separate the pieces, although limited, would seem to argue against an analysis that treats the CP simply as a zero level verb. The present account offers an explicit account of the range of lexical and phrasal properties of these CPs, simultaneously capturing both its lexical and phrasal properties. 3. Additional Zero Level Properties 3.1 Changes in Argument structure The complex predicate often differs in its argument taking properties from the corresponding simple verb. For example, in simple sentences, gereftan, “to take,” may occur with an explicit source argument: (3) ketâb râ az man gereft book ACC from me took S/He took the book from me. When used as a light verb in the CP arusi gereftan, “to throw a wedding,” the benefactive barâye phrase appears: 8 In other instances, what might otherwise be considered a host can appear with a determiner; the full NP (or DP) can be modified, relativized, gapped, and coordinated (Karimi-Doostan 1997). 5 (4) a. barâye u arusi gereftam for her/him wedding took I threw a wedding for her/him. In this case, the CP as a whole does not allow a source argument: (5) b. * az u arusi gereftam from her/him wedding took 3.2. The existence of transitive CPs On a phrasal account of Persian CPs, nominal hosts would presumably be treated a direct object argument of the verb, since it often has the semantics of a direct object and it does not occur with a preposition. However, several of the Persian CPs are transitive, taking a(nother) direct object as the examples in (6) and (7) illustrate: (6) Ali-râ setâyeS Ali-acc adoration I adored Ali. kardam did.1.sg (7) Ali Babak-râ nejât dâd Ali Babak-acc rescue gave.3sg Therefore, the light verbs involved would have to be analyzed as double object verbs. But there are no verbs in Persian other than CPs that take two objects. Therefore the double object analysis would be an ad hoc way of accounting for transitive CPs. 3.3 Nominalizations Another piece of evidence for lexical status is the ability to form nominalizations, since nominalization is a process that applies to zero level items. Persian CPs can form nominalizations by attaching the present stem of the light verb to the host: (8) V: bâzi kardan Lit., “game + do” (“play”) N: bâzikon “player” (as in soccer player) (9) V: negah dâStan: Lit. “HOST + have” (to keep) N: negahdâri: maintanance (10) V: ruznâme neveStan “newspaper + write” (“to write newspapers”) N: ruznâmenevis “journalist” Complex predicates can also serve as input to gerundive nominalizations and adjectival past participles, both of which apply to simple verbs in an identical manner (KarimiDoostan 1997: 61). One might wonder whether these constructions really form compounds since compounds are known to take as input two independent words, not a single zero level category. Compound formation is readily identifiable in Persian 6 because compounds are formed by inserting an ezafe morpheme (/e/) between the two zero level items; the ezafe is not found between the two elements of the CP in these lexicalization patterns, however, demonstrating that the CP is indeed treated as a single zero level item. A final piece of evidence arguing that the complex predicate must be considered a zero level entity comes from the fact that the host and the light verb resist certain types of separation. 3.4 Host and Light Verb Resist Separation Separation by Adverbs In sentences without CPs, adverbs can freely appear directly before the verb: (11) maSq-am-râ tond neveStam homework-1.sg-def.ACC quickly wrote.1.sg I did my homework quickly. However in the case of CPs, the adverb does not separate host from light verb (12). Instead, the adverb precedes the entire CP (13): (12) ??rânandegi tond kardam driving-N quickly did.1sg Intended, “I drove quickly.” (13) tond rânandegi kardam quickly driving-N did.1.sg I drove quickly. Separation by DO Further undermining a phrasal account of the CP is the fact that the host and light verb resist separation by the DO in the case of transitive CPs, even though DOs normally appear before the verb: (14) ?? setâyeS Ali-râ kardam adoration Ali-acc did.1.sg Intended, “I adored Ali.” Instead, the DO appears before the entire CP as in (15) above, repeated below: (15) Ali-râ setâyeS Ali-acc adoration I adored Ali. kardam did.1.sg 5. The complex predicate construction 7 The evidence presented so far indicates that Persian CPs have many properties that standardly identify zero level items. On the basis of these properties, we posit a construction that treats the CP as a V0, labeling it the CPvo construction: Cat: V0 Χ0 < V0 Figure 1. The CPvo construction The box notation is used to simultaneously represent the internal constituents and external status of the construction. The external syntax of the complex predicate is that of a V0 category; the internal syntax includes two zero level categories, a host (represented by the variable X0) and a V0. The host may be a noun, an adjective or a preposition. The host immediately precedes the V0 (indicated by the ‘<’)9. The “/” over X0 is intended to indicate that the host receives the primary stress. We will see below that certain more specific constructions serve to override the construction’s external V0 status, and it is in this way that the V0 status of the CP is a default. But before turning to these overrides, it is worth addressing the motivation for the CPvo construction. Ackerman and LeSourd (1997) observe that once independent syntactic forms begin to be associated with properties of complex predicates such as joint meaning or composite argument structure, they take on the status of stored phrasal forms. This, however, can be viewed as a marked option since over time, such complex predicates tend to coalesce into syntactically and phonologically atomic lexical items through a process of grammaticalization (see also Mithun 1984, Gerdts and Hinkson 1996 for discussion of this diachronic tendency in the phenomenon of noun incorporation). The construction captures the stage in the synchronic grammar in which the unmarked expression of a complex predicate is as a V0. The diachronic facts themselves are motivated. The preference for treating the CP as a single syntactically integrated predicate is motivated by its status as a semantically integrated predicate. This can be seen to be a special case of a general iconic principle: namely, a tight semantic bond between items tends to be represented by a correspondingly tight syntactic bond (Givón 1980; 1991; Haiman 1983; Bybee 1985). Notice that on this view, the most “natural” situation is one in which semantic scope and syntactic structure are aligned (cf. the “mirror principle” of Baker 198810). 9 This notation appears also in Hudson (this volume). Baker’s Mirror Principle is stated as a relation between morphology and syntax, not morphology and semantics. However, since syntax on Baker’s view is assumed to be isomorphic to semantics, the principle can be construed as capturing a relation between morphology and semantics. 10 8 At the same time, it is recognized that semantic scope and syntactic scope do not necessarily align (see also Ackerman, this volume). Constructions, given that they specify form and meaning and the relation between the two, readily allow for such mismatches. Below we will see that the complex predicate does not always appear as a V0, but may appear as a phrasal entity when it co-occurs with certain other elements. One implication of this proposal is that words and phrasal constructions are treated as the same basic type of entity. Not only can both types of patterns be stored, but moreover, one and the same stored construction can appear either as a single morphological word or as a phrasal entity. This possibility can be accomodated within theories such as Construction Grammar, Cognitive Grammar or HPSG, in which grammar consists of constructions which are not-strictly predictable form – meaning patterns that are morphological or phrasal (e.g., Fillmore, Kay, & O'Connor 1988; Pullum & Zwicky 1991; Fillmore & Kay 1993; Goldberg 1992, 1995; Jurafsky 1992, Lakoff 1987, Langacker 1987, 1991; Pollard & Sag 1987). The idea that there are generalizations in languages that are sometimes violated due to competing motivations has been a long held tenet of various functional approaches (cf. Haiman 1985, Bates & MacWhinney 1987, Langacker 1990, and Lakoff 1987), and has recently gained in currency via Optimality Theoretic approaches to grammar (Prince & Smolensky 1993; Legendre et al. 1993; Grimshaw 1995; Bresnan 2001). We will see that the default inheritance hierarchy allows us to capture these violable generalizations in a natural way. Let us turn now to certain situations in which the host and light verb do not appear as a V0, but rather as two pieces of a phrasal structure. The complex predicate can be separated by a number of elements, including the future auxiliary, imperfective and negative prefixes, and direct object clitics. 6. Syntactic Properties 6.1. CPs are separated by the future auxiliary The standard word order in Persian is SOV, with different auxiliaries appearing in different fixed positions before or after the main verb. When the future auxiliary, xâstan, is used with simple verbs, it appears immediately before the main verb, which appears in its simple past form as in (16): (16) Ali mard-râ xâhad Ali man-acc future-3.sg Ali will hit the man. ZAD hit (simple verb) This is captured by Figure 2: future xâstan-agr < V0past 9 Figure 2: the Future Auxiliary Construction The future marker is semantically a verbal operator in that it predicates tense of the event described by the verb. Thus, the word order generalization that the future auxiliary and V0 appear immediately adjacent in the string is motivated by the same iconic consideration mentioned earlier: elements that are closely related semantically tend to appear close together in the syntactic string. When a CP is involved, xâstan must appear between the host and light verb as in the following example: (17) (man) telefon I telephone “I will telephone.” xâham FUT-1.sg kard did (CP) Positioning the future auxiliary before the entire CP is not permitted: (18) * (man) xâham I FUT-1.sg telefon telephone kard did (CP) Given the hypothesis that the CP is a V0 (by default), it is not predictable that the future auxiliary must intervene between the host and light verb. Notice that the auxiliary cannot naturally be treated as an infix within a lexical unit because of its person and number inflection. Inflectional morphology occurs outside derivational morphology in the vast majority of cases. Thus the requirement that xâstam must intervene within the CP is a not-strictly-predictable morphologically-specific fact. It is therefore necessary to posit a future-CP construction that specifies a particular word order. The future-CP construction is located lower on the hierarchy than the general future construction, and the general CP construction insuring that the specifications of the future-CP construction override the specifications of the more general constructions. Figure 3 represents the proposal: CPV0 Future Cat V’ xâstan-agr Cat V0 < V0 past Χ0 < V0 V0 Future-CP X0 < xâstan <V0 past 10 Figure 3: the Future-CP construction + CPv0 Construction The links in Figure 3 (and in the diagrams below) are simple instance or “ISA” links (see discussion in Hudson, this volume). Constructions at the base of the arrow are the dominating or mother constructions, constructions at the tip of the arrow are the dominated or daughter constructions that inherit from their mother nodes. Motivation for the marked word order of the future-CP construction can be found in the diachronic history of the CP. Notice that the future auxiliary is a closed class or grammatical element. It is generally recognized that the ordering of grammatical elements is often motivated by a diachronically earlier stage of the language (Givón1971; Bybee 1985). In particular, this type of complex predicate is generally recognized to arise diachronically from complement + verb expressions cross linguistically (Mithun 1984).11 At the time when the elements that today are complex predicates were analyzed as complement and verb, it was completely natural that the verbal tense operator should appear between the complement and the verb. This reflects the general ordering of complements in Persian: S O Fut V.12 The construction, used only in written Persian and more formal spoken contexts, simply retains the word order from this earlier stage of the language. 6. 2 Imperfective prefix and negation The imperfective and negative prefixes, mi- and na- respectively, are attached directly to the light verb, thus intervening between host and light verb. They may not appear as prefixes on the host element. Since the host and light verb form a V0 category by hypothesis, these facts are on the face of it, unexpected. However it is possible to explain the data by recognizing an important implication of a usage-based default inheritance hierarchy. Each of the light verbs involved in Persian CPs appears as a highly frequent main verb as well. Unremarkably, in their main verb uses, mi- and na- appear as prefixes. As noted earlier, we know from psycholinguistic research that highly frequency forms are stored even when they are fully regular (Losiewicz 1992; Bybee 1995). It is therefore natural to expect that the full forms, e.g., mi-kardan, na-kardan, etc. are stored in the lexicon, due to their high frequency. A representation of what is stored regarding the imperfective mi- prefix for a few verbs is provided in figure 4. 13 11 A similar verbal auxiliary intervenes between host and verb in the preverb + verb construction in Hungarian (Farrell Ackerman, personal communication), and also in Walpiri (Nash 1980). 12 While the placement of the auxiliary between complement and verb is somewhat unusual crosslinguistically, Hans Henrich Hock (personal communication) observes that it is also attested in Vedic Sanskrit. Hock speculates that it may have arisen from a tendency to extrapose verbal complements when the auxilaries involved were main verbs. For present purposes, what is important is that the position of the auxiliary between the main verb and DO complement can be used to motivate the position of the auxiliary between the light verb and host in the CP construction. 13 Figure 4 assumes that the stored forms abstract over particulars of agreement morphology. This assumption is not critical to the present account; it may be that more specific forms such as mikardam(imp-DO-1st), mi-kardi(imp-DO-2nd), mi-kard (imp-DO-3rd), etc. are stored. 11 12 Imperfective-V0 mi-V0 mi-neviStan mi-zadan mi-kardan mi-xâxan mi-daStan Figure 4: A subset of stored usage-based knowledge regarding the imperfective mi- prefix 13 Since in a usage-based hierarchy, more specific stored forms preempt or block the creation of forms based on a more general pattern, the existence of forms mi-kardan, and na-kardan block the possibility of adding the prefixes directly to the zero level CP as a whole, given the simple assumption that the light verb involved in a CP is recognized as the same verb as its corresponding main verb (represented by the double arrow: each verb instance stands in an ISA relation with the other instance of the same verb). For experimental evidence that speakers do identify the two uses of the morphological verb form see Karimi-Doostan (1997: 91). CP “turn on” roSan kardan “light” “to do” kardan “to do” Imperfective V0 mi-V0 mi-neviStan mi-zadan mi-kardan mi-xâxan mi-dâStan Figure 5 14 At the same time, any newly coined simple verbs would be expected to readily accept the mi and/or na prefixes since nothing would block their being generated by the higher level generalization. New verbs that are not CPs are exceedingly rare, but this prediction corresponds to native speaker intuition about novel forms. The usage-based model thus accounts for the facts in a very straightforward way. If there were a CP that involved a verb stem that did not have an independent use as a main verb, we would expect that the prefixes would attach to the host of the uninterrupted CP, which by hypothesis is a V0. This prediction cannot be readily tested, however, since each light verb appearing in a CP also appears as a main verb. 6.4 CPs can be separated by DO clitics In the case of simple verbs, direct object clitics appear directly after the verb, as in (19): (19) didam -aS see.past.1.sg 3.sg.CL I saw it. In the case of CPs, the DO clitic normally appears directly after the host, thus separating host from the light verb as in (20): (20) roSan -aS kard light -3.sg.CL did S/He turned it on. Pronominal elements may not appear in the middle of single zero level categories. That is, the clitic cannot occur between syllables in a multisyllabic single word, even after a stressed morpheme boundary. Therefore, the possibility of inserting the pronominal clitic within the CP provides a strong piece of evidence that the host and light verb should be analyzed as two separate words in (20). This implies that there is another construction in conflict with the CPvo construction. What is required is a construction that positions the clitic in second position within the predicate, after a stressed zero level category. This construction can be posited directly under the general simple verb + clitic construction as in Figure 6. Simple verb + clitic V’ predicate / V0-CL CP+clitic V’ predicate / X0-CL < V0 15 Figure 6: Clitic position constructions Figure 6 predicts that the CP + clitic construction, which specifies that the clitic should intervene between host and light verb, will preempt the more general simple verb + clitic construction. That is, Figure 6 predicts that while (21) is possible, (22) is unacceptable. (21) masxareh -aS kardand joke -3.sg.CL did.3.pl They made fun of him. (22) masxareh kardand -aS joke did.3.pl -3.sg.CL They made fun of him. For many speakers, this is accurate, and the representation in Figure 6 is confirmed. At the same time, other speakers allow the clitic to follow the light verb in the case of CPs as another option in addition to allowing the clitic to intervene between host and light verb. For these speakers, a slightly different hierarchy, represented in Figure 7, is warranted. CL2: Generalization over clitic constructions V’ predicate Y0-CL Simple verb + clitic CP+clitic V’ predicate V’ predicate V0-CL X0-CL < V0 Figure 7: Different version of Clitic constructions reflecting dialect variation Since neither the simple verb + clitic construction nor the CP + clitic construction is more specific than the other (dominated by the other) in Figure 7, neither construction preempts the other. That is, Figure 7 treats the CP + clitic and the simple verb + clitic construction as sisters, both dominated by a more general, neutral construction. Thus the representation in Figure 7 predicts that the clitic may appear either after the host or after the entire CP. In the latter case, the fact that the CP is a V0 by default comes into play. As a V0, it meets the requirements for the simple verb + clitic construction, allowing the clitic to appear after the CP. It may seem to be a vice and not a virtue that either the 16 representation in Figure 6 or that in Figure 7 is possible; however, the empirical data are ambiguous so any theory that only predicted one possibility or only the other would be bound to fail. What enables both analyses in this particular instance is the fact that, considered theoryneutrally, it is not clear whether or not the CP + clitic construction should actually be considered more specific than the simple verb + clitic construction. The two constructions simply differ in their input specifications. CPs are arguably more specific than simple verbs, but they far outnumber simple verbs and appear more frequently than simple verbs. The empirical ambiguity may have actually led to an underdetermination of the hierarchy, leading some speakers to form the representation in Figure 6 and others to form the representation in Figure 7. The simple verb + clitic construction, the CP + clitic construction and the more general CL2 construction are all motivated the same way: from the stress facts outlined in section 1. Clitics, as dependent elements, only attach to stressed elements in the clause. Thus the specification in all instances that the Persian clitic must attach to a zero level category that receives stress is natural: in the case of simple verbs, stress falls on the V0; in the case of CPs, stress falls on the host.14 Both the representations in Figure 6 and Figure 7 make a prediction that the clitic must appear directly after the host element when the future tense is involved. This is because when the future tense intervenes between host and light verb, the CP is not a V0 but a V’, and therefore cannot serve as input to the simple verb + clitic construction. Since the host remains stressed in the future tense, the clitic must attach to the host. This prediction is borne out by the facts: speakers only accept the clitic on the host as in (23) and reject outright examples like (24) in which the clitic appears after the light verb, when future tense separates host and light verb: (23) masxareh -aS xaxand joke -clitic future-pl They will make fun of him. kard do (24) *masxareh xaxand kard-aS joke future-pl do-clitic Intended, They will make fun of him. To summarize, I have claimed that although the CP is necessarily listed in the lexicon, it is not necessarily a zero level item. The general CP construction has the external syntax 14 The clitic constructions are also all motivated to some extent by Wackernagel's Law, that specifies that clitics should appear in second position in the sentence. Wackernagel’s law holds of Walpiri, SerboCroation, Luiseño, Greek, and Sanskrit (Anderson 1994; Bubenik 1994; Halpern 1995). The motivation lent by Wackernagel’s Law is less strong because in the case of Persian, the clitic appears in second position within the smaller domain of the predicate, not the sentence. Also, Wackernagel’s Law itself cries out for some kind of motivation. 17 of a V0; but the grammar also has more specific constructions that serve to override the specifications of the general construction. The CPvo construction serves to account for a wide range of properties strongly associated with zero level status, including the formation of nominalizations, the resistance to separation, the stress facts and possible non-compositional argument structure. The fact that the future auxiliary intervenes between host and light verb required a constructional analysis, since it is not strictly predictable; it was independently motivated however by general word order facts of Persian and the diachronic history of the CP as a verb + complement. The possibility of the clitic intervening between host and light verb required another construction; this construction was strongly motivated by stress facts. It was demonstrated that the appearance of the imperfective and negative prefixes required no special constructions that made any reference to CPs. A diagram of all the relevant constructions, whether CP-specific or not, and their interactions is given in Figure 8. A. Future-general V’ C. Clitic-general B.CPv0 V’ V0 xâxam < Χ0 V0 V0 Y0-CL E. CP + clitic D. Future-CP V’ V’ Χ0 < < xâxam < V0 X0-CL < V0 Figure 8: A summary of the constructions critical for accounting for Persian CPs and their zero-level and phrasal properties It is important to keep in mind that each of the three mother constructions (A, B and C in Figure 8) has been independently motivated. The two daughter constructions (D and E in Figure 8) are motivated by the constructions they inherit from; exceptional aspects of the daughter nodes’ specifications were also independently motivated. That this full range of facts can be accounted for by the 5 interrelated, interconnected, motivated constructions, situated in a default inheritance hierarchy, which is itself needed on non-linguistic grounds, presents an advance over other current approaches to the phenomenon. 7. Alternative Accounts 7.1 Ranked Constraints 18 Goldberg (1996) suggests analyzing the Persian data as involving a set of typologically natural ranked constraints and adopts the formalism of Optimality Theory for her exposition (Smolensky and Prince 1993). In many ways the present and earlier accounts are consistent. Both share the idea that the Persian CP is a V0 by default and that V0 status is overridden only if there is an independently motivated constraint or construction. The present account is preferable however on theoretical and empirical grounds. The default hierarchy is independently useful for capturing much general, learned knowledge in a simple and intuitive way. As argued elsewhere, it is likewise useful for capturing many other sorts of linguistic generalizations (Hudson, 1990 this volume; Lakoff 1987; Goldberg 1995). Moreover, a careful look at the data reveals that the generalizations, although motivated, are in fact construction-specific. For example, only the future auxiliary and not any other auxiliary in Persian must intervene between the host and light verb. It is possible to motivate this fact, but it remains a morphologically-specific fact. Standard OT, on the other hand, claims that each constraint is universal, existing in each language. Given the construction-specific nature of the data, positing a constraint with any implication of universality is unwarranted. A further theoretical advantage to using a default inheritance hierarchy is that it is partially ordered: not every construction is ordered with respect to every other construction. Only constructions that are plausibly related or interact appear as immediate sisters, daughters or mothers of other constructions. By contrast, the constraints in OT are assumed to be fully ordered15. Thus the future-CP facts would have to be ordered either higher or lower than, for example, the constraints required to insure appropriate relative clause formation, even though the constraints involved are unrelated and never come in conflict with each other. The OT representation in Goldberg (1996) required 3 constraints and additionally required the 3 constraints to be rank ordered; the rank ordering was posited to capture what happens when conflicts between the 3 constraints arise. Figure 8 likewise involves 3 mother constructions; also parallel is the fact that the two daughter constructions exist in order to specify how conflicts between the 3 mother constructions are resolved in the grammar. Thus positing daughter nodes with conflicts resolved is equivalent to stipulating a rank ordering of constraints. The only additional empirical prediction that was made in Goldberg (1996) involved where clitics may appear when the predicate appeared with the future tense morpheme. The same correct prediction is made by the DI hierarchy, as discussed in section 6.4. To this extent, the two accounts capture the empirical facts isomorphically. 15 In actual practice, many OT accounts rely on two constraints that share the same spot in the linear hierarchy to account for free variation (as in, e.g., Goldberg 1996). But while inheritance hierarchies generally assume a network of constructions not a linear ordering of constructions, OT analyses assume a strict linear ordering, modulo possible cases of two constraints ranked at the same spot. 19 The present account goes beyond Goldberg (1996) in empirical coverage. Goldberg (1996) failed to account for the imperfective and negative facts. It was recognized that additional morphologically specific constraints would be needed and would need to be rank ordered with respect to the other constraints. Intuitively, it was clear that the empirical facts seemed too obvious to warrant such stipulation. In fact, the present account allows us to explain those facts without any grammatical stipulation. A usage based model of inheritance serves to capture the fact, for example, that the specific stored element mi-kard preempts the spontaneous creation of, for example, *mi-roSan kard. Complex predicates have been the focus of a great deal of attention lately. Theories which draw a strict division between zero level categories and phrasal entities do not allow for the possibility that one and the same stored entity could appear as either a word or a phrase depending on what other constructions it interacts with. Instead, researchers have attempted to retain the strict division between words and phrases in various ways. Below are several additional alternative proposals. 7. 2 A Scrambling Analysis Massam & Ghomeshi (1994) note the fact that direct object clitics and auxiliaries can intervene between host and light verb in Persian CPs as we have already seen, and they therefore conclude that the CPs cannot be zero level items. However, their analysis seems to actually propose a morphological and not a phrasal account of Persian CPs. Specifically, they propose that CPs are formed by adjoining an X0 to V0 under a V0 node (as a base generated structure). That is: (25) V' --> V0 --> X0 V0 Since positing the mother V0 node implies that CPs are words, 16 the various zero-level properties of Persian CPs can in fact be accounted for straightforwardly on their analysis. In fact, we argue here that the idea that the CP can be treated as a V0 is essentially right. It is the phrasal properties that are not sufficiently accounted for. Ghomeshi and Massam invoke scrambling to explain how certain entities are allowed to intervene between host and light verb. However, various word order possibilities in Persian involve maximal categories, not X0 categories as would be required to separate host from light verb. In addition, no constraints on the scrambling operation are discussed; for example, no account is offered as to why the direct object clitics and certain auxiliaries in particular can intervene between host and light verb. The scrambling account is therefore not fully explanatory, since it is not independently motivated and is not adequately constrained. 7.3 Generating the CP Phrasally Other accounts propose generating the complex predicate phrasally. Such accounts have focused much attention on how to account for the often non-compositional meaning of 16 Although see Sells (1994) for an account in which X0 phrases are generated syntactically. Taking this option would mean that Ghomeshi and Massam would not account for the various lexical-like properties of the CP. 20 the complex predicate. That is, the semantics of many complex predicates is fairly compositional, as in the following examples: (26) ?anjâm dâdan performing give “to perform” (27) ? âqâz kardan beginning + do “to begin” However, other CPs are noncompositional or non-transparent in that the meaning is not predictable from the complex predicate's component parts. For example, consider (28) and (29): (28) guS kardan ear do “to listen” (29) dust dâStan friend have “to like/love” To listen is not literally “to do ear;” to like is not literally “to have a friend.” It is argued in the following sections that the semantics is not naturally attributed either to the host or light verb in isolation, but rather to their combination. These facts are actually neutral between a zero level and phrasal account of Persian CPs on the present assumptions, since we assume that zero level items, non-compositional phrases and idioms are all stored in the constructicon. Nonetheless, the following sections critique proposals that have suggested that the apparently non-compositional semantics is actually specified solely in either the host or the light verb. 7.3.1 An Argument Transfer Proposal Mohammad and Karimi (1992) argue that the entire semantic content comes from the nominal element, and that the verbal element is semantically empty. The evidence given to support this claim is the existence of a few cases wherein varying the verb does not result in a noticable change in meaning. For example, (30) ezhâ kardan/dâStan statement + to do/to have = “to state” (31) majbur kardan/ nemudan forced + to do/to show = “to force” 21 Interestingly, ezhâr dâStan in (30) is archaic and is only used in literary contexts. In fact, the actual number of such doublets in current use is vanishingly rare. It is clear that in the majority of cases, a change in the V does result in a change in meaning. For example, (32) gul zadan / gul xordan deceit + strike / deceit + eat “to deceive” / “to fall for the deception” (33) dar âvardan / dar âmadan door + bring / door + come “to take off/out” / “ to come out” (34) entexâb kardan / entexâb shodan choice + do / choice + become ”to choose”/ “to be chosen” In addition, if the light verb were truly semantically vacuous, with the host supplying all of the semantics, one might expect that there would be only one or two light verbs. However, there are a large number of light verbs, which implies that the language would have to tolerate many trivially synonymous forms. The following are sixteen light verbs (provided in order of frequency, following Karimi-Doostan 1997): kardan “do”; zadan “hit/beat”: dâdan “give”; gereftan “hold/take”; dâStan “have”; âmadan “come”; âvardan “bring”; xordan “eat”; keSidan “pull/tolerate”; yâftan “find”; Sodan “become”; bordan “take/carry”; raftan “go”; gozâStan “put”; didan “see”; baxSidan “forgive”. Alternatively, one might expect that the existing light verbs would be in free variation with each other: any host combining with any light verb. However, hosts are quite particular about which light verbs they can occur with. For example: (35) *komak zadan / komak kardan help strike / help do = “ to help” (36) *madrak kardan / madrak gereftan degree do / degree take = “ to get a degree” Therefore, the semantics of the Persian CP is not naturally assigned to the host in isolation (see also Schultze-Berndt 1998 on CPs in Jaminjung). 7.3.2 Idiomatic Argument Analysis An alternative would be to posit the full meaning in the light verb. The host could be claimed to be a regular argument of the verb, semantically selected for by the special meaning of the verb.17 For example, kâr kardan, Lit. “job + do,” meaning “to work,” would be analyzed as a special sense of kardan. This verb would be claimed to mean “to work” and would be understood to semantically select for the nominal argument kar. A parallel analysis has been suggested by Nunberg, Wasow and Sag (1994) for “deformable” idioms in English. 17 22 The non-compositional meaning and changes in argument structure would not be mysterious on this account because those special properties would be captured in the special sense of kardan. However, an account of the zero level properties of Persian CPs discussed in section would be required. While no explanation would be required to explain why the host can be separated from the light verb: the host and light verb would be separable just as any argument + verb combination is separable. However, the account predicts that Persian CPs should be generally separable as are general DO + verb combinations in Persian. As we have seen, however, CPs only separable in certain specific circumstances. In addition, on this account, the light verb would have to select, not only for the semantic type of its argument (which would be unremarkable), but also for its definiteness and specificity characteristics: the hosts must be indefinite and nonspecific.These characteristics usually mark the particular noun's role in discourse, and are not specified by the verb. That is, we do not generally find unique stems in a language that are differentiated only by the definite/specificity characteristics of their arguments: such specifications are not typically part of a verb's meaning. Finally, recall that certain CPs with nominal hosts are transitive, a fact that undermines a phrasal account, since one would be hard pressed to analyze both the host and the direct object as direct objects of the verb, given that Persian does not allow double object constructions elsewhere. In short, there are ways in which the host does not act like a regular argument of the verb. Therefore simply treating the host as an argument does not account for the full range of data. One might suggest in response to these criticisms of phrasal accounts that Persian CPs exist both as syntactic phrases and as zero level items. This brings us to another possible proposal. 7.4 Creating the CPs either in the lexicon or in syntax There has been a growing body of work that allows complex predicates to be formed either in the lexicon, as traditionally construed, or in the syntax (Butt 1995; Butt, Isoda and Sells 1990; Matsumoto 1992; Mohanan 1994; Williams 1997.) Alsina (1993) for example, has argued that causatives in certain languages, e.g. Chichewâ, are formed in the lexicon, while those in other languages, e.g. Catalan, are formed in the syntax. Only CPs formed in the lexicon are understood to undergo nominalizations. Only CPs formed in the syntax are claimed to be separable. Nothing prevents such a theory, though, from claiming that a single language has both types of complex predicates (see in fact Mohanan 1994 for such an analysis in Hindi). And in fact, this option would be necessary to account for languages like Persian. We 23 have already seen that the Persian CP allows nominalizations, while at the same time it allows its pieces to be separated in certain circumstances. Therefore the CPs have one property of lexical entities and another property of phrasal items. Such predicates would presumably have to be generated both lexically and phrasally. There are several drawbacks to this approach. First, is not clear where the idiosyncratic semantics of certain CPs “formed in the syntax” would be specified. As discussed in the previous two sections, there are problems with positing the semantics exclusively either in the host or in the light verb. Instead, the semantics only arises in their combination. In addition, if lexical CPs were available along with phrasal CPs, we would expect that speakers would never be required to separate host from light verb: the option of using an inseparable lexical CP should exist. However as we saw above, the future auxiliary necessarily intervenes between host and light verb. Therefore the lexical-and-phrasal account would have to constrain the lexical CPs from ever appearing with the future tense. Unless some independent motivation can be found, this stipulation is very difficult to defend. Finally, while the Persian CP is separable under certain conditions, claiming that the CP is formed “in the syntax” does not explain the constraints on separability described earlier. That is, the way in which the Persian CPs fail to show the full range syntactic properties, particularly in being not freely separable, remains unaccounted for. 8. Conclusion To summarize, I have argued that the Persian complex predicate is represented in the lexicon as a unit, despite the fact that it does not necessarily appear as a syntactically atomic zero level category. This possibility is predicted by theories such as Construction Grammar, Cognitive Grammar and HPSG, in which both words and phrasal entities are stored in the mental lexicon or “constructicon.” The idea that items with some phrasal properties can be listed in the lexicon alongside syntactically atomic lexical items is also supported by Ackerman (this volume), Ackerman and Webelhuth 1998, Fillmore, Kay and O’Connor 1988; Goldberg 1995; Jackendoff 1997, 2002; Nunberg et al. 1994; Williams 1994; Culicover 1999. Added to the recognition of the fact that status as a stored entity does not entail atomic syntactic status, is the claim that status as a word can be assigned on a default basis. This claim implies that there can be no strict division within the “constructicon” between words and phrasal elements. One and the same stored item can be realized as either a zero-level word or a phrasal entity, depending on what other constructions it co-occurs with. The notion of a default construction was made concrete by positing other more specific constructions that serve to override specifications of the more general construction. The network of constructions and the relevant properties of default inheritance were made explicit. Motivation for each construction was suggested by noting its adherence to more 24 general tendencies, such as an iconic principle that allows a semantic bond to be represented by a correspondingly close syntactic bond. References Ackerman, Farrell, this volume. Morphosyntactic mismatches and realization-based lexicalism. Ackerman, Farrell and Philip LeSourd. 1996. Toward a Lexical Representation of Phrasal Predicates. In Complex Predicates. A. Alsina, J. Bresnan and P. Sells, eds. Stanford: CSLI Publications. Ackerman, Farrell and Gert Webelhuth. 1998. A theory of predicates. CSLI Publications. Baker, Mark C. 1988. Incorporation: A Theory of Grammatical Function Changing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Barlow, Michael and Suzanne Kemmer. 2000. Usage-based models of language. Stanford: CSLI publishers. Bates, Elizabeth and Brian MacWhinney. 1987. Competition, Variation and Language Learning. In B. MacWhinney (ed) Mechanisms of Language Acquisition. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Bresnan, Joan. 2001. Lexical-Functional Syntax. Oxford: Blackwell. Bresnan, Joan and Sam Mchombo. 1995. The Lexical Integrity Principle--Evidence from Bantu. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory. Butt, Miriam. 1995. The Structure of Complex Predicates in Urdu. Stanford: CSLI Publications. Bubenik, Vit. 1994. On Wackernagel's Law in the History of Persian. Indogermanische Forschungen, 99. 105-122. Bybee, Joan. 1985. Morphology. John Benjamins Press. Bybee, Joan. 1995. Regular Morphology and the Lexicon. Language and Cognitive Processes 10 (5): 425-455. Croft, William. 2002. Radical Construction Grammar. Oxford University Press. Culicover, Peter. 1999. Syntactic Nuts. Oxford University Press. 25 DiSciullo, Anna Maria and Edwin Williams. 1997. On the definition of word. Cambridge: MIT Press. Fillmore, Charles, Paul Kay and Mary Catherine O'Connor. 1988. Regularity and Idiomaticity in Grammatical Constructions: The Case of Let Alone. Language 64: 501538. Fillmore, Charles and Paul Kay. 1993. Construction Grammar. University of California, Berkeley. Flickinger, Daniel Paul. 1987. Lexical Rules in the Hierarchical Lexicon. PhD Thesis. Stanford University. Givón, Talmy. 1980. The Binding Hierarchy and the Typology of Complements. Studies in Language 4 3: 333-377. Givón, Talmy. 1991. Isomorphism in the Grammatical Code: Cognitive and Biological Considerations. In Studies in Language 15-1. 85-114. Gerdts, Donna and Mercedes Hinkson. 1996. Salish Lexical Suffixes: A case of decategorialization. In A. Goldberg (ed) Conceptual Structure, Discourse and Language. Stanford: CSLI Publications. Ghomeshi, Jila and Diane Massam. 1992. Lexical/Syntactic Relations without Projection. Linguistic Analysis. Goldberg, Adele E. 1995. Constructions: A Construction Grammar Approach to Argument Structure. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Goldberg, Adele E. 1996. Words by Default: Optimizing Constraints and the Persian Complex Predicate. Berkeley Linguistic Society 22. Grimshaw, Jane. 1995. Ms. Projection, Heads and Optimality. Rutgers University. Haiman, John. 1985. Natural Syntax: Iconicity and erosion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Halpern, Aaron. 1995. On the Placement and Morphology of Clitics. Stanford: CSLI Publications. Hudson, Richard. 1984. Word Grammar. Oxford: Blackwell. Hudson, Richard. 1990. English Word Grammar. Oxford: Blackwell. Jackendoff, Ray. 1975. Morphological and Semantic Regularities in the Lexicon. Language 51 3:639-371. 26 Jackendoff, Ray. 1997. The Architecture of the Language Faculty. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press. Jackendoff, Ray. 2002. Foundations of Language. Oxford University Press. Karimi-Doostan, Gholamhossein. 1997. Light Verb Constructions in Persian. PhD thesis, University of Essex. Kiparsky, Paul. 1968. Linguistic universals and linguistic change. In E. Bach and R. Harms (eds.) Universals in Linguistic Theory. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. 171-202. Lakoff, George. 1987. Women, Fire and Dangerous Things. Chicago: Chicago University Press. Lambrecht, Knud. 1994. Information Structure and Sentence Form: topic, focus and the mental representations of discourse referents. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Lambrecht, Knud & Laura A. Michaelis. 1998. Sentence Accent in Information Questions: Default and Projection. Linguistics and Philosophy 21: 477-544. Langacker, Ronald. 1990. Concept, Image, and Symbol: the cognitive basis of grammar. New York: Mouton de Gruyter. Legendre, Geraldine, William Raymond and Paul Smolensky. 1993. An OptimalityTheoretic typology of case and grammatical voice systems. BLS 19 464-487. Losiewicz, B.L. 1992. The effect of frequency on linguistic morphology. PhD thesis, University of Texas, Austin. Marantz, Alec. 1997. No Escape from Syntax: Don't try Morphological Analysis in the Privacy of Your Own Lexicon. A. Dimitriadis L. Siegel (eds.). University of Pennsylvania Working Papers 4.2. Massam, Diane and Jila Ghomashi. 1994. Lexical/Syntactic Relations without Projection. In Linguistic Analysis 36, 337-361. Matsumoto, Yo. 1992. On the Wordhood of Complex Predicates in Japanese. Stanford University dissertation. Michaelis, Laura A. & Knud Lambrecht. 1996. Toward a Construction-Based Model of Language Function: The Case of Nominal Extraposition. Language 72:215-247. McCarthy, John and Alan Prince. 1993. Generalized Alignment. In Yearbook of Morphology 1993, ed. G. Booij and J. van Marle. 97-153. Dordrecht: Kluwer. 27 Mithun, Marianne. 1984. The Evolution of Noun Incorporation. Language 60: 4. 847894. Mohammad, Jan and Simin Karimi 1992. Light Verbs are Taking Over: Complex Verbs in Persian. Proceedings of Western Conference on Linguistics. 175-186. Mohanan, Tara. 1994. Argument Structure in Hindi. Stanford: CSLI Publications. Murphy, Gregory L. and Hiram H. Brownell. 1985. Category differentiation in object recognition: typicality constraints on the basic category advantage. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning Memory and Cognition. 11 1: 70-84. Nash, David George. 1980. Topics in Walpiri Grammar. MIT Dissertation. Nunberg, Geoff, Tom Wasow and Ivan Sag. 1994. Idioms. Language. Prince, Alan & Paul Smolensky. 1993. Optimality Theory: constraint interaction in generative grammar. RuCCS Technical Report &#2. Rutgers University Center for Cognitive Science. Piscataway, NJ. Pullum, Geoffrey K. and Arnold M. Zwicky. 1991. Condition Duplication, Paradigm Homonymy and Transconstructional Constraints. BLS 17:252-266. Saussure, Ferdinand de. 1916. Course de linguistique generale. Paris: Payet, 1973. Translated by W. Basikin. New York: McGraw Hill, 1976. Schultze-Berndt, E. 1998. Making sense of complex verbs: generic verb meaning and the argument structure of complex verbs in Jaminjung. Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, Nijmegen, The Netherlands. Sells, Peter. 1994. Sub-Phrasal Syntax in Korean. Language Research. Williams, Edwin. 1994. Remarks on Lexical Knowledge. Lingua 92. 7-34. Williams, Edwin. 1997. Notes on Lexical and Syntactic Complex Predicates. In A. Alsina, J. Bresnan, and P. Sells (eds) Complex Predicates. Stanford: CSLI Publications. Windfuhr, Gernot. 1979. Persian Grammar. New York: Mouton. 28 29