I will tell you a story about two men

advertisement

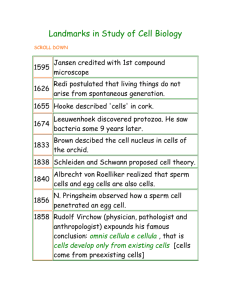

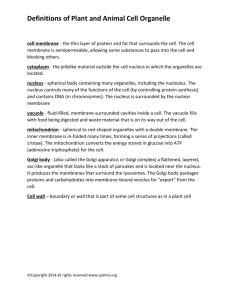

Golgi and Cajal I will tell you a story about two men. Camillo Golgi. Santiago Ramon y Cajal. An Italian and a Spaniard. Both studied the brain, both shared the Nobel prize for their combined contributions. Both made invaluable discoveries and jumpstarted neuroscience into the 20th century. They are eternally bound. Yet they were bitter, lifelong enemies. Earlier ideas about the nervous system. Plato believed that the mind was in the brain. He envisaged a system of elements, switching on and off, not unlike neurons. But since there was no way the old Greeks could actually investigate the brain, he had no idea what these elements looked like. He deduced that they were perfect triangles. Descartes believed that the soul/mind and brain were two separate entities. Res extensa and res cogitans. The mind controlled the body through the pineal gland, a small center perfectly located centrally in the brain. The body was entirely mechanical, the nervous system was a system of ‘tubes’, like aqueducts. Through them, fine particles moved. “animal spirits”, sent messages and controlled the system that was the body. But like these two great minds, whatever scholars thought about the brain was bound to be nonsense until they could actually look at it. And while you can easily see the walnut-shaped macroanatomy of a dead animal brain, the microstructure, what the brain is actually made of remains inscrutable to the naked eye. That is why the study of the brain only truly began when a particularly relevant invention had been made. The microscope. Starting with van Leeuwenhoek, Galileo, and other pioneers, the microscope became better and better, with increasingly fewer distortions, and increasing enlargement. Nerves were anyway starting to become a field of real interest. An important contribution was by Luigi Galvani, who showed that nerves operate by conductance of electricity. He decapitated a frog, attached electrical wires to the spinal cord, and made the frogs legs jerk by injecting electricity. Thus, people turned to improving microscopes to the brain. Around the time of Golgi and Cajal, microscopes had reached the sophistication that slices of brain could reveal some stuff going on. In 1836, Purkinje successfully identified the Purkinje cells in the cerebellum, particularly large mothers. He and his coworkers demonstrated with limited tools that there were essentially two materials in the brain: isolated globules (grey matter), and fibers (white matter). From here, two main camps evolved. Reticularists. Neuronists. All of it was speculative, but early on, influential thinkers preferred the network theory. All the same, until well into the 19th century, a slice of brain would be never be more than a homogeneous, messy, tangled web of stuff. First half of the 19th century, histologists started to use reagents, chemicals to fix, stain, and process slices of tissue. This resulted in histologists actually seeing stuff, although it wasn’t always real anatomical stuff. Golgi spent his initial researches fixing the slices, the reagents, and showing that other people were wrong, that their observed stuff were actually artefacts of the tissue preparation. Life of Santiago Ramon y Cajal. The story of Santiago starts with his dad. Don Justo lost both his parents when he was 12. To make a living for himself, he was apprenticed to a barber surgeon, cutting hair and letting blood, in the countryside – village called Larres. After 10 yrs, at 22, he decided to learn more about being a physician, and walked 200 miles to Barcelona. There he studied with professionals, took courses at the university, read books. He returned to his countryside village a more educated man. It wasn’t long before he was a respected and successful physician around the area, which allowed him to marry his childhood sweetheart. He was hard-working, diligent, a devoted family man. When he had his sons, he took a particular interest in their education. This went so far, that he took his son, Santiago, to a deserted Shepard’s cave. Working hard, things were looking up for Don Justo and his family. They moved to a larger town, Ayerbe. Santiago was 8 yrs old, and in fact a little odd. He didn’t particularly care about that, but the boys of Ayerbe did. They bullied him, to the physical. Not one to cry at home, Santiago actually worked his way up to become their captain. This was possible because Santiago, at heart, was a little anarchist. “in the bottom of every juvenile head, there is a perfect anarchist” From anarchy, Santiago went to art-madness. He drew and painted, and decided that was what he wanted. Don Justo, a practical man, didn’t appreciate. But a fair man as well, he decided to ask for an educated opinion. The only painter around was a housepainter, and he decided that S. stank. Santiago didn’t appreciate, and Don Justo packed him off to live with an uncle and be educated by a bunch of tough friars. This bored Santiago, and he got interested in building weaponry. His local friends were particularly impressed when he decided to build a cannon. He took a great wooden beam and painstakingly holed it out. He carefully assembled the thing, built a trigger system with an oil can, and looked for a target. They dragged it to the top of a hill, aimed it at a brand-new garden gate of a neighbor’s house, and loaded it with cobblestones and gunpowder. Fully expecting the cannon to blow up, the boys were mystified when the thing worked and actually blew up the garden gate to bits. So mystified, that they forgot to run, and were taken by the police. Don Justo and the local mayor put him in a rotting jailcell for three days. It didn’t help, because S. continued to build muskets and the like, until he made another cannon, this time of bronze, and this time it did blow up. His father tried everything, different schools, apprenticeship to a barber, until he completely gave up. He brought S. home and apprenticed him to a shoemaker. There, S. finally realized the hopelessness of such a life endeavor and begged his father for another chance. Skeptically, D.J. agreed, and to his surprise S. did actually do better, graduating in the end in medicine. Ironically, it was also then, when S. applied his lifelong passion for drawing, to anatomy, producing valuable and universally appreciated depictions of things he studied. Better work ethic, but not less stubborn and obstinate, S. ran into trouble when he was drafted to Cuba at 22. Dismayed at the corruption displayed by his superiors, he ran into all kinds of trouble, causing his by his resistance against these practices. Later, when he fell seriously ill, he recovered, barely, by steadfastly doing everything opposite to the doctor’s advice. When he met a girl he liked, he married her in secret, when both their parents decided they were too young and too poor to have an immediate future. Santiago was never stopped by the advice or considerations of others when he felt a passion. And it was a passion for microscopy that started him of in earnest. On returning from Cuba, he visited Madrid for his doctoral exams. He met with a friend there, who showed him a webbed frog’s foot, where the microscope revealed small corpuscles moving through the arteries and veins. Cajal was ridiculously excited by this view into the deeper mechanisms behind things, and wanted a microscope for himself. When he moved to Valencia into a new position at the university, he spent all his money on one, and set it up in his home. After dinner, dishes and family were removed from the kitchen, and Cajal would go to work. He made slices of things to look at, study under the microscope, and draw. He then compared these things to each other, seeking meaning and order. His interest was soon drawn by the mysterious nature of the brain. After preparing slices, S. would often go play chess around midnight, in the busy nighlife cafes. Characteristically, he played aggressively and recklessly, and with a passion. In the early morning he would look at his slices again, and often take a sheet of fine drawing paper to bed, with a pen and ink. He would proceed to carefully draw out his observations. The ink in his pen would dry quickly, so he would flick the end of it. In the morning, he always quarreled with his wife, trying to explain how there came to be black splatters all over the bedroom wall. Life of Golgi Golgi was a more uneventful man, and his story can be shorter. He did well in school, strived for and achieved academic excellence, and went on to become a man of medicine. He initially studied with a psychiatrist, but began in earnest when he attended the lab of Bizzozero, a young professor, and some interesting friends and colleagues. After showing other people wrong, getting properly into this field of histology, Golgi suddenly and sadly had to quit the lab. There was no more money for him to pursue this interest – his father advised him to get a stable job and income. He took such a job in a hospital with patients that didn’t require much actual care, so he spend the evening in his kitchen with a microscope, similar to Cajal. Perhaps because he had nothing much to do, he explored different reagents and chemicals to fix and stain the tissues that he explored under the microscope. By most probably an accident, he discovered the reazione nero: the black reaction. This method of staining had the wonderful advantage that only a few percept of neurons were stained (blackened) by the chemicals, but then in their entirety. Thus, these neurons could be followed and studied without the overwhelming presence of all the other neurons. This method led to such a flurry of research papers by Golgi that many discoveries were for all intents and purposes buried beneath less important or false notions. Perhaps because of this, Cajal wasn’t aware of all the things Golgi had at one point claimed, and at a later point may have repeated and extended some discoveries, receiving credit that Golgi felt more entitled to. Golgi and Cajal Cajal, upon seeing slices with the Golgi stain became so enthusiastic that he doubled his efforts. He immediately saw the enormous possibilities, and was intrinsically motivated to make the most of this black reaction. In the process, he improved the method, now called double impregnation, making neurons even more clearly visible, and urging him on in his efforts. Where Golgi was the father of the method, he principally drew all the wrong conclusions about the brain – claiming that neurons were not separate entities, but reflections of one big network called the reticulum. Cajal, instead, saw and noted that neurons were separate building blocks of the brain, connecting to each other at contact points later called ‘synapses’. For his contribution, Golgi received the Nobel prize. He had to share it with Cajal, who had taken the basis from Golgi and went much further, and thus contributed hugely to the field of neuroscience. While Golgi was important methodologically, Cajal was important theoretically. Unfortunately, Golgi could not accept Cajal’s theories, which ultimately led him to make a fool of himself when receiving the nobel prize. In his speech, he vehemently (putting it mildly) denied the neuron doctrine, holding fast without reasonable argumentation to the reticular theory that was by then accepted by nearly no-one, excepting of course Golgi himself. Read this story and more in Richard Rapport’s ‘Nerve Endings’.