Strategies and Boundaries - Warwick Research Archive Portal

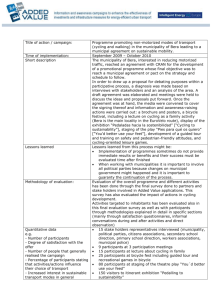

advertisement