The public history of goods from the East

JM

2.12.2012

Ships, spices and museum spaces: The public history of ‘goods from the East’

John McAleer (University of Southampton)

As research projects like ‘Europe’s Asian centuries’ have powerfully demonstrated,

Asian commodities have long played a central role in western societies: the financing and logistics of their importation had a huge impact on European shipping and overseas trade, encouraging the growth of European trading companies; their sale and widespread distribution affected European patterns of consumption and taste; and expanding and defending access to Asian markets led, in part at least, to the development and maintenance of European global empires in the early modern period.

Recent scholarship has further enriched our understanding of the ways in which goods, such as spices, textiles and tea, affected European societies. This impact was mediated principally through the agency of various East India companies, whose ships were responsible for the vast quantities and varieties of goods which were imported from Asia. This paper considers how the complex history of Europe’s relationship with ‘goods from the East’ might be realised in practice for general museum audiences, by exploring the representation of the East India trading companies, their commercial activities, and their trade in commodities in a number of different museum and public-history contexts.

The discussion examines the role of museums in a number of European cities with a long history of Asian commercial connections, and the UK’s National

Maritime Museum (NMM) in particular, as crucial conduits through which the stories of Eurasia’s trading worlds might be brought to a wider general public. And it explores some of the ways in which new research and changing historiographical trends have influenced the interpretation of this history in the recent past. It also touches on ways in which this history is being reinterpreted and harnessed to lubricate present-day Asian-European commercial, cultural and political relationships. In doing so, this paper investigates the possibilities offered, as well as the challenges presented, by surviving material culture for displaying the general themes of the conference: goods and production; retail and consumption; and networks of trade.

The paper begins by outlining some of the object selections and interpretive strategies pursued by the NMM and other museums in order to highlight the impact of

‘goods from the East’ on European societies and the continuing relevance of this history today. It posits the central role of ships, sailors and the sea in bringing Asian goods to European consumers, and suggests that the maritime context of these

Eurasian trading networks is a key issue for presenting and understanding the world of Europe’s East India companies. To this end, the discussion considers ways in which ships, and other maritime-related material culture, might be employed in museum contexts, using surviving material culture evidence, to highlight important historical moments and to challenge established historiographical approaches.

The paper concludes by considering if and how multiple interpretations of objects can offer avenues to access the complex nature of this history. Can the immediacy of the story be preserved while, at the same time, paying attention to the nuances of the history? Is it possible to use European East India companies – and the

Page 1 of 15

JM

2.12.2012 wider ramifications of Europe’s centuries-long maritime trade with Asia – as a springboard for introducing broader themes about the history of European imperialism and global history to general audiences?

Museums and European East India companies: temporary exhibitions

Recently, over two centuries after the demise of most of the European monopoly trading companies, there has been a renewal of scholarly interest in, and recognition of, the fundamental role played by objects and material culture in shaping the history of the European encounter with Asia.

1 This has been inspired by new academic interests and trends in historiography. And this has been matched by a wider public interest in this history, fostered through popular history books, such as

Nathaniel’s

Nutmeg by Giles Milton.

2

It has been assisted by the fashion for writing ‘commodity histories’.

3

And this foray into popular culture has been apparent in other media too, such as the special ‘guest appearances’ by the British East India Company in the

Pirates of the Caribbean film series.

4

As crucial cultural arbiters for bringing history into the public arena, museums and galleries have also been at the forefront of this process. Their institutional remit for using material culture and objects would seem to make them particularly well-placed to explore, examine and interpret a history founded on the supply, movement and consumption of goods.

There has always been a lively interest in presenting the history of goods from the East in Western museums. As with its European competitors, material culture formed a crucial part of the British East India Company’s mercantile, corporate and political identities, and there is a long history of the representation of the company’s activities in museums. Company activity led to the establishment of the India

Museum, an institution specifically dedicated to collecting and displaying material from Asia. But the East India Company also contributed to the collections and displays of a range of different museums in Britain.

5

Similarly, the Peabody Essex

Museum, in Salem, Massachusetts, was established for the purpose of displaying the results of American trading contact with Asia based on the collections of the East

The author was Curator of Imperial and Maritime History at the National Maritime Museum (NMM) from 2006 to 2012. He would like to thank his colleagues, Dr Robert J. Blyth and Dr Nigel Rigby, for their help and assistance in preparing this paper. The views and interpretations represented in this article are the author’s, and do not necessarily reflect those of the NMM.

1 P. J. Marshall, ‘The Great Map of Mankind’, in Alan Frost and Jane Samson (eds) Pacific Empires:

Essays in honour of Glyndwr Williams (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1999), pp.

237–50, p. 238.

2 Giles Milton, Nathaniel’s Nutmeg: How one man’s courage changed the course of history (London:

Hodder and Stoughton, 1999).

3 See Bruce Robbins, ‘Commodity histories’, Proceedings of the Modern Language Association 120: 2

(2005), pp. 454–63.

4 See Philip J. Stern, ‘History and historiography of the English East India Company: past, present, and future!’, History Compass 7:4 (2009), pp. 1146–80.

5 See John McAleer, ‘Displaying its Wares: Material culture, the East India Company and British encounters with India in the long eighteenth century’, in Gabriel Sánchez Espinosa, Daniel Roberts and

Simon Davies (eds), Global Connections: India and Europe in the long eighteenth century (Oxford:

Voltaire Foundation, forthcoming, 2013).

Page 2 of 15

JM

2.12.2012

India Marine Society.

6

In these contexts, India and China were often presented as being particularly ‘wealthy and exciting’.

7

By the late twentieth century, however, exhibitions on this theme of European commercial contact with Asia were often refracted through the lens of later colonial and post-colonial history. They tended to be temporary shows, often based in art museums or galleries and apparently more interested in issues of representation, and the distribution and collection of luxury items, than the mechanics and logistics involved in getting them to Europe (or America) in the first place. For example, in

1990 the National Portrait Gallery hosted The Raj: India and the British, 1600–1947 .

It was one of the first exhibitions to confront the complexities of this history and the material culture it produced. The exhibition brought together objects that explained individual lives, both British and Indian, and their responses to the British presence in

India. By virtue of its location and emphasis, however, the exhibition (a temporary display) naturally focused on issues of artistic representation. It tackled such themes by charting the ‘creation and projection of Indians and their lives, and of Indian images of the British’ through the selection, display and juxtaposition of a range of paintings, miniatures and other objects.

8

The title and chronology chosen clearly advertise the fact that the exhibition went well beyond the story of the East India

Company and its trade in commodities; in fact, it explored the origins, development and eventual demise of British India, setting the commercial activities of the East

India Company in a much wider context. At that time, it was the largest show ever mounted by the gallery. Fittingly, the gallery’s then director, John Hayes, promised a suitably wide-ranging experience for visitors, focusing on ‘the long relationship between the peoples of one of the great ancient civilisations of the East, … and the representatives of a vigorous Western trading nation’.

9

The vigorous trade that acted as a key motivation for drawing the two together, however, seemed somewhat underplayed.

In 2004, Encounters: The meeting of Asia and Europe, 1500–1800 was held at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. It too sought to address the varied nature of the encounters, relationships and misunderstandings between Asians and

Europeans in the period, again through the medium of material culture. The geographical and chronological remit was broader than The Raj , however, and it used a greater variety of object types. As the editors of the exhibition catalogue explained,

Encounters explored ‘from a broad perspective the way in which Asians and

Europeans responded to one another’.

10 The exhibition explicitly recognised that it

6 See Walter Muir Whitehall, The East India Marine Society and the Peabody Museum of Salem: A sesquicentennial history (Salem, MA: Peabody Museum, 1949).

7 James M. Lindgren, ‘“That every mariner may possess the history of the world”: A cabinet of curiosities for the East India Marine Society of Salem’, The New England Quarterly 68:2 (1995), pp.

179–205, p. 185.

8 C. A. Bayly (ed.), The Raj: India and the British, 1600–1947 (London: National Portrait Gallery,

1990), p. 11.

9 John Hayes, ‘Foreword’, in Bayly (ed.) The Raj , p. 8.

10 Anna Jackson and Amin Jaffer, ‘Introduction: The meeting of Asia and Europe, 1500–1800’, in

Anna Jackson and Amin Jaffer (eds), Encounters: The meeting of Asia and Europe, 1500–1800

(London: V&A, 2004), pp. 1–11, p. 5.

Page 3 of 15

JM

2.12.2012 was not just the material culture of the East India Company that explained the

European encounter with Asia in the eighteenth century. As Oliver Impey pointed out, most of the objects on display powerfully demonstrated the fact that East and West were unusual, unfamiliar and, indeed, exotic to each other during the period.

11

In this context, one might also consider how the activities of other European trading companies have been represented by museums. The events and exhibitions held across the Netherlands in 2004 to commemorate the four-hundredth anniversary of the establishment of the Dutch East India Company, Vereenigde Oostindische

Compagnie (VOC), are a case in point. The commemorations were the product of a campaign to engage the Dutch public with this history, even if the meaning of that commemoration was contested. Schools were provided with educational materials, while a range of museums across the country ‘mounted a vast array of exhibitions on the VOC, its exploits and the implications of Dutch-Asian trade for the metropolis’.

12

One of the most impressive museum exhibitions was ‘De Nederlandse ontmoeting met Azië, 1600–1950’ (‘The Dutch Encounter with Asia’), which opened in October

2002 at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.

13

The exhibition was accompanied by an lavish catalogue.

14

In a similar vein, the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery and the National

Museum of African Art in Washington DC combined to organise Encompassing the

Globe: Portugal and the world in the 16th & 17th centuries . This exhibition brought together over two hundred and fifty objects with the express purpose of illustrating a

‘world in formation’. As one might expect, a large part of the exhibition was devoted to Portuguese trade with Asia, which created ‘a framework for global interaction that endured for centuries’.

15

Commodities on show: permanent displays in London, Gothenburg, Uppsala and

Amsterdam

All of these temporary exhibitions were characterized by the fact that they brought together a panoply of impressive objects, from widely dispersed collections around the world. Accompanied by sumptuous catalogues, they focused on the surviving material culture: generally luxurious and spectacular; precious and unique records of cultural encounter and interaction. But, European East India trading companies were, at their most basic, organisations interested in mundane, diurnal and comestible

11 For a variety of reasons, the term ‘exotic’ is one that British museums have increasingly eschewed in the recent past. Encounters was originally to have been called ‘Exotic Encounters’. One can only assume that the epithet was dropped by someone less familiar with the subject matter than those organising the exhibition and writing the catalogue. See Oliver Impey, ‘Review of The meeting of Asia and Europe ’, The Burlington Magazine 146 (2004), p. 773.

12 Gert J. Oostindie, ‘Squaring the circle: Commemorating the VOC after 400 years’, Bijdragen tot de

Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 159:1 (2003), pp. 135–61, p. 145.

13 Ibid., p. 154.

14 See Kees Zandvliet and Leonard Blussé (eds), De Nederlandse ontmoeting met Azië, 1600–1950

(Amsterdam; Zwolle: Rijksmuseum Waanders, 2002). See also the Rijksmuseum website: http://www.rijksmuseum.nl/aria/aria_themes/7136?lang=nl (accessed 23.11.2012).

15 Jay A. Levenson (ed.), Encompassing the Globe: Portugal and the world in the 16th & 17th centuries , 3 volumes (Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution, 2007), vol. 3, p. 9.

Page 4 of 15

JM

2.12.2012 objects. Their main business involved the transportation of huge quantities of commodities – spices, tea, porcelain and swathes of textiles – back to Europe for sale, fundamentally altering ideas of taste and dress for millions of people. Ironically, the tangible, material and physical items on which the East India companies based their commercial success were ephemeral and few examples have survived, making the elucidation of this aspect of their history particularly challenging for curators, exhibition organizers, and museum visitors alike.

Over the past number of years, however, interest has grown in presenting the more workaday aspects of this history to museum goers. In 2002, the home of the

British East India Company’s extensive archives mounted a major exhibition to showcase this material, which was accompanied by an illustrated companion history, public lecture series, and a continuing online exhibition. The British Library’s

Trading Places: The East India Company & Asia, 1600–1834 explicitly focused on the ‘remarkable story’ of the Company’s history. But the organisers were keen to point out that this was not ‘merely a history of the past’; rather, the exhibition sought to impress visitors with the ‘lasting impression on life in both Britain and Asia’ made by the Company and proclaimed that ‘its legacy is a story of today’.

16

As a commercial organisation, the Company’s activities were meticulously recorded in ledgers, daybooks and letter books that stretch for miles on the shelves of the British

Library’s storage rooms. An exhibition at this particular venue, drawing on this wealth of material, offered an opportunity to focus on the mechanics of trade and the logistics of shipping large quantities of goods around the world, as well as the impact of this business on British society. The exhibition did not rely solely on the twodimensional archives in the library’s care; it borrowed widely from other museums such as the National Maritime Museum and the British Museum in a bid to evoke the world preserved in the archival records.

17

Away from their institutional or archival ‘homes’, as it were, the story of

European countries’ trading relationships with the East is perhaps most appropriately displayed in history museums. In the United Kingdom, one of the principal museums of ‘national history’ is the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich (NMM). As an institution which played a significant part in Britain’s maritime history, presenting the

East India Company to audiences is something with which the NMM has been intimately involved over the years.

18

Indeed, its collections of material in this area

– from ship models and ship portraits, to manuscripts and medals – make this one of the museum’s most important non-naval narratives. The preponderance of paintings entitled ‘An East Indiaman in a stiff breeze’ or ‘An East Indiaman at anchor’ (of which there are, literally, hundreds in the collection) should not disguise the fact that

16 See http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/features/trading/exhibition1.html

(accessed 23.11.2012).

17 See, for example, Anthony Farrington, Trading Paces: The East India Company and Asia, 1600–

1834 (London: British Library, 2002), pp. 23–4, 89.

18 For the early history of the museum, see Kevin Littlewood and Beverley Butler, Of Ships and Stars:

Maritime heritage and the founding of the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich (London: The

Athlone Press, 1998).

Page 5 of 15

JM

2.12.2012 identifying objects with which to tell a suitably rounded and balanced history of the

Company was not an easy task for those involved.

The museum has been at the forefront of new approaches to maritime history over the past few decades, confronting similarly vexed historiographical challenges, which encompass the presentation of this kind of subject to today’s museum audiences.

19

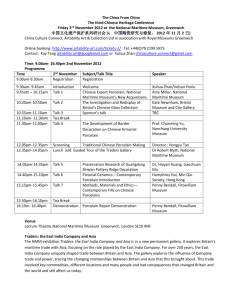

The latest iteration of this approach to presenting maritime and imperial history opened in 2011. This new gallery, originally code-named ‘Asian Seas’, is entirely devoted to the history of the East India Company. Traders: The East India

Company and Asia represented the changing world of maritime history and its presentation to the general public. This is the first permanent gallery dedicated to the history of the Company in its hometown. Traders and the collection upon which it draws, reflect the fact that aspects of the Company’s history, ignored or skirted over in the past, can be retrieved by the use and display of material culture. The gallery was predicated on two key concepts or intellectual organising principles. First, the commodities of the East India Company and their impact on British society; and, second, the importance of the maritime aspect to this broader history.

Briefly, the narrative is arranged in five key sections. The gallery begins by introducing visitors to the people, places and cultures of the Indian Ocean World before the arrival of the European trading companies. Using some of the Museum’s unique collections of Asian ship models, ethnographic material, and other interpretative devices, this section evokes the complexity, diversity, and sophistication of cultures and trading activities in the Indian Ocean. Following this introductory space, visitors move into a long gallery that uses a combination of material culture, text panels, visual images and interactive displays to tell the history of the East India

Company in a roughly chronological progression.

This part of the display situates commodities at the heart of the interpretation strategy. The narrative of the gallery – the core, organising principle around which the objects are interpreted – was constructed using four key ‘commodities’ traded by the

Company and which characterized its career at different phases of its development: spices, textiles, tea and power. The ‘Spice Trade’ section explores the beginnings of the English East India Company: a small operation that lagged far behind its

European rivals in the luxury trade in expensive Asian spices. In the eighteenth century, the Company’s interests shifted from spices to textiles, and from South East

Asia to India. It became a cloth merchant to the world, developing markets for highquality textiles in Britain and beyond. The visitor then follows the Company as it attempts to break into the lucrative tea trade centred on China and strictly controlled by the Emperor. The last section of the gallery focuses on the ramifications of the

Company’s trading activities: the Company’s administration of India and its downfall

19 On this subject, see R. J. B. Knight, ‘Making waves’, History Today 4 (April 1999), pp. 3–4; and

Margarette Lincoln and Nigel Rigby, ‘Reinventing maritime history’, History Today 7 (July 2001), pp.

2–3.

Page 6 of 15

JM

2.12.2012 following the Opium Wars with China, and the Indian ‘Mutiny’ of 1857.

20

The gallery was accompanied by a book that used the museum’s collection to tell the maritime history of the East India Company.

21

One of the challenges faced by any museum is the nature and constraints of its collections, the contexts in which they were acquired and the accretion of historical interpretations which can sometimes limit the interpretative possibilities of the objects. In the NMM’s case, the strong naval narratives running through the museum’s collections and its historical displays have often drawn on objects from

Asia. In the Traders gallery, however, the limited range of Asian goods in the museum’s collection were interpreted in the context, not of naval history, but rather mercantile and commodity history. For example, a sailor’s neckerchief or bandana worn by Samuel Enderby at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805 has generally been interpreted in this context in the past. In the Traders gallery, however, it is displayed together with objects that illustrate the impact of the trade in textiles on British taste and fashion.

22 Similarly, Chinese export porcelain collected by James Cook, which was presumably acquired by the museum because of its connection with this iconic figure in British maritime history, is interpreted as part of the interest in all things

Chinese which riveted British society in the eighteenth century.

23

And the vase presented by the Queen of Naples to Horatio Nelson – perhaps the most iconic of all the naval personalties associated with the Museum – is also displayed and interpreted in this context.

24

Given the limited number of surviving examples in the museum’s collection, the exhibition also employed interpretative devices, such as ‘info-graphics’ and video footage, to explore elements of the history of the trade.

One might also cite the permanent exhibition devoted to eighteenth-century

Gothenburg in that city’s Stadsmuseum. In many respects, it is impossible to ignore the history of the Swedish East India Company in this museum as it is located in the former East India House in the city.

25

The exterior frieze of the building pronounces that what is now the Stadsmusuem once housed the headquarters of Svenska

Ostindiska Companiet (the Swedish East India Company). Fresco decoration inside the building, dating from the 1890s, briefly alludes to the history of the Swedish trading relationship with Asia too. But the richest and most complete engagement with the history of Asian trading is found in the ‘1700s Gothenburg’ exhibition, which opened in June 2010. It seeks to trace the history of ‘a city in transformation’, and it uses the explosion of commercial activity in the period partially to explain the

20 Further information on the gallery and the objects on display may be found on the museum’s website: http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections.html#!csearch;exhibitionReference=subject-

90730;authority=subject-90730 (accessed 23.11.2012).

21 See H. V. Bowen, John McAleer and Robert J. Blyth, Monsoon Traders: The maritime world of the

East India Company (London: Scala, 2011).

22 Object number: TXT0284. See http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/71099.html

(accessed

23.11.2012).

23 Object numbers: AAA6192–5. See Bowen, McAleer, and Blyth, Monsoon Traders , pp. 108, 111.

24 Object number: AAA4723. See Bowen, McAleer, and Blyth, Monsoon Traders , pp. 108, 110.

25 A useful introduction to the activities of the Swedish East India Company in English may be found in Robert Hermansson, The Great East India Adventure: The story of the Swedish East India Company

(Gothenburg: Breakwater Publishing, 2004).

Page 7 of 15

JM

2.12.2012 changes wrought on the city and wider region. The large central display case displays a range of commodities and objects that evoke eighteenth-century Gothenburg’s trading connections with the wider world. At the heart of the exhibition is the trade in goods from the East: ‘Tea, silk, and East Indian porcelain was shipped into town and sold at auction in the East India House where the City Museum is housed today.’ 26

The exhibition includes displays relating to tea, coffee and tobacco. The survival of porcelain in greater quantities makes it easier to acquire than other items, and its greater durability makes it more feasible to display on a permanent basis. The interpretation of the objects underlines the connection between this domestic commodity and the global trading networks that brought it back to Sweden. In fact, as the gallery interpretation makes clear, porcelain from China had ‘a real impact on

Sweden’, with some fifty million pieces imported by the Swedish East India

Company during its lifetime. The exhibition also displays porcelain specifically commissioned for individual families, such as the Gullbringa dinner service, brought back by Hans Henrik Clason, a captain in the Company’s employ.

27

The display of porcelain, mainly because of its availability and durability, is a common shorthand employed in museums for representing the theme of East India

Company trade. It appears in this context in a number of Swedish museums: from the

Nordiska Museum in Stockholm to Linnæus’s House in Uppsala. In the latter instance, the house incorporates the story of Asian trade into the general narrative of the great botanist’s domestic routine and ritual.

28

Thus, visitors are told that ‘Mrs

Linnæus’ entertained her husband’s guests with tea and coffee, served in the porcelain pieces that adorn the house. Linnæus ordered two dinner services from China, which were ‘probably acquired due to Linnæus’s connection with the Swedish East India

Company’.

29

The first was ordered and carried back by one of his disciples, Pehr

Osbeck in 1752. However, when it returned bearing incorrect foliage on the twobloom flower that was his ‘trademark’ (

Linnea Borealis ), illustrations for a second service from Linnæus’s own Flora Sverica were sent to the Chinese craftsmen.

30

As with the British and Swedish examples in their respective countries, the

Dutch Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie had a crucial influence on the commercial and cultural development of the Netherlands in the country’s ‘Golden Age’. Thus, Het

Scheepvaartmuseum in Amsterdam adopts a similar approach in some of its displays to those discussed above. The impact of the VOC on the Netherlands is brought home

26 References to the gallery are derived from the Stadsmuseum website: http://stadsmuseum.goteborg.se/wps/portal/stadsmuseum (accessed 23.11.2012)

27 Information from museum object labels, July 2012.

28 In addition to the porcelain, a range of other objects in the house allude to the botanist’s connection with the wider world in general, and the impact of Asian trading networks on this part of rural northern

Europe in particular. Other objects on display include: Chinese textiles; porcelain and a punchbowl made by the Rörstrand Factory, which used tin glaze to make it appear more ‘Chinese’; imported soapstone figures; and Linnæus’s medicine chest, made from camphor from China.

29 Information from museum object labels, June 2012.

30 A similar practice may be seen in relation to a punch bowl on display in the Traders exhibition, which was ordered by a Mr Barnard, the owner of a number of shipyards (object number: AAA4440).

See Bowen, McAleer, and Blyth, Monsoon Traders , p. 113.

Page 8 of 15

JM

2.12.2012 most forcefully perhaps in the newly refurbished glass, silver and porcelain displays.

31

The centerpiece of this gallery is the personal dinner service of Rear Admiral C. F.

Wolterbeek. The coat of arms, which includes a Bengal tiger and an elephant, as well as the legend ‘Malacca’, gives a clue as to the origins of the service, which was apparently awarded to this Dutch naval officer by the Sultan of Malacca. The gallery reinforces the importance of Dutch commercial and political connections with Asia by displaying gifts and commemorative pieces associated with it. For example, behind one of the cabinet doors that visitors are invited to open is a silver plate produced to commemorate the life of Jacob Sadelijn, director of the Bengal office of the Dutch

East India Company, who died in 1732.

32

Ships and the maritime context

Despite the importance of surviving material such as porcelain and textiles, the fundamental role of the maritime context in the interpretation and elucidation of the history of European East India companies is one of the central challenges for museums today. Until recently, and notwithstanding the fact that the trade of

European East India companies was a maritime one, often there was little consideration of the ships themselves, the crew or the passage of time taken. Just as porcelain can make the domestic impact of Asian trade very immediate for museum goers, so the display of ships can often appear intimidating and alienating for visitors with a limited knowledge of, or apparent connection with, the sea.

33

For example, take the explanation of the arrival of tea cuttings in Sweden offered in the Orangery, operated by the University of Uppsala, which adjoins the house of Carl Linnæus. The exhibition, ‘Linnæus and his Garden’, includes a section on the ‘long wait for tea’, which includes a range of episodes that chart the passage of tea to Linnæus in Uppsala.

34

Generally, the story of the ship is downplayed. More broadly, the historiography of the British Empire in Asia is often characterized by its doggedly land-based perspective. This is not necessarily surprising, given the size of the Indian subcontinent and the important role played by India in later manifestations of the British Empire. But this only tells part of the story: everything that moved between Asia and Britain during the time of the East India companies, and vice versa, from cargoes to people, ambassadors to rhinoceroses, travelled on ships.

The ship – as a physical artefact, and represented in various museum collections in a variety of media – can play a crucial role in conveying that broader context of Europe’s engagement with the wider world, as well as the interweaving of

31 See http://www.hetscheepvaartmuseum.nl/exhibitions/exhibits|32 (accessed 23.11.2012).

32 Information from museum object labels, September 2012.

33 See Gert Oostindie’s point that one cannot rely on ‘audience knowledge’: ‘What is known and particularly not known by the general public is not primarily an expression of political or scholarly decisions on content. Knowledge and awareness of the national past in Dutch society simply does not run deep.’ See Gert J. Oostindie, ‘Squaring the circle: commemorating the VOC after 400 years’,

Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 159:1 (2003), pp. 135–61, p. 137. This is a point that is also highlighted in R. J. B. Knight, ‘Making waves’, History Today 4 (April 1999), pp. 3–4.

34 Information from museum label, July 2012.

Page 9 of 15

JM

2.12.2012 naval history and national identity. In his Principles of Naval Architecture (1784),

Thomas Gordon remarked: ‘As a ship is undoubtedly the noblest, and one of the most useful machines that ever was invented, every attempt to improve it becomes a matter of importance, and merits the consideration of mankind’.

35

The ship still has a role to play in telling the histories of empire; through careful display and thoughtful interpretation, ships can make important points and convey a much wider story.

Het Scheepvaartmuseum in Amsterdam has a particular advantage in this regard as it can call on the very large object moored just outside its door: an exact replica of the Dutch East India Company ship Amsterdam , lost on her maiden voyage in 1749.

36 But even where this is not a possibility – for example in the permanent displays in Greenwich and Gothenburg – the ‘ship’, as an archetypal object, has been harnessed for interpretative effect better to convey the mechanics and logistics of the trade in goods from the East, as well as the longer-term ramifications for this in

Europe.

In the NMM, the ‘ship’ is technically not a collection-item type. But ships are tangible objects, and the ship is the classic maritime artefact. And the ship has, of course, been one of the great constants running through the museum’s institutional history. But approaches to the interpretation of ships have not been constant; they have changed, atrophied, evolved and developed.

Just as the historiography of the

British Empire has changed over the past few decades, it bears underlining that historiographies of the ship (and approaches to ship interpretation) have been moulded and reshaped by new academic trends. One might think of the idea of the ship as a classic symbol of modern technology.

37

Recent research has considered how ships operated as self-contained communities. The idea of the ship – in particular, the slave ship in the eighteenth-century Atlantic Ocean – as a defined social space has been explored in the work of people like Marcus Rediker, Peter Linebaugh and Emma

Christopher.

38

All of this renewed or reawakened or even newly discovered academic interest in the ship has a number of implications for people working with the material culture of Britain’s maritime, naval and imperial history. One of the most powerful of these is a realisation that these objects can provide insights not just into life at sea or into the correct way to rig a cat-built bark, but that they can shed light on broader questions pertaining to British history.

35 Quoted in Marcus Rediker, The Slave Ship: A human history (London: John Murray, 2008), p. 41.

36 For further information, see http://www.hetscheepvaartmuseum.nl/exhibitions/exhibits|33 (accessed

23.11.2012).

37 See, for example, Carlo Cipolla’s Guns, Sails and Empires: Technological Innovation and European expansion 1400–1700 (New York: Pantheon, 1966), in which he attribute the hegemony of Western

Europe between 1400 and 1700 to two technological developments: cast-iron cannon and ‘round ships’.

38 Marcus Rediker, The Slave Ship: A human history (London: John Murray, 2008); Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker, The Many-Headed Hydra: The hidden history of the revolutionary Atlantic

(Boston, MA: Beacon, 2001); Marcus Rediker, Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea: Merchant seamen, pirates and the Anglo-American maritime world, 1700–1750 (Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 1987); Emma Christopher, Slave Ship Sailors and their Captive Cargoes, 1730–1807

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Page 10 of 15

JM

2.12.2012

The display and interpretation of ships in the Traders exhibition made a point about the maritime nature of the enterprise: it was all done on ships and, as such, long-distance maritime trade made a huge difference to the developing world economy; and it had a major impact on the domestic British economy. In this latter regard, a painting depicting East India Company vessels being constructed at

Deptford in the mid-seventeenth century – close to the site of the museum – makes an important point about the impact of Asian trade on the domestic economy and its contribution to the growth of cities such as London.

39

Elsewhere in the exhibition,

Indiamen in the South China Seas , a painting by William John Huggins, is included, giving a sense of the cultural impact of the Company and its burgeoning trade.

40

Before setting up as an artist, Huggins had sailed on East Indiamen and established a studio adjacent to the headquarters of the Company on Leadenhall Street – an indication of the strong demand among captains and Company directors for shipinspired material culture.

41

In his work then, ships need to be seen not simply as vehicles of maritime commerce, but also as symbols, indicative of wealth, status, position and power.

In Gothenburg, the centrality of the sea to this trading world is emphasized by the display of a large, detailed and well-preserved ship model. It represents the type of ship used to trade with China and has been in the East India House since the establishment of the museum in the 1860s. The model probably represents the

Götheborg , the second ship to bear the name, which foundered in Table Bay,

Southern Africa, in 1796. The model itself was made at the end of the eighteenth century and, as the museum label informs visitors, was a status symbol for its owner.

42

In its current guise, the ship model powerfully reinforces the message that eighteenth-century Gothenburg’s wealth and status was dependent on the sea and the ships that sailed it. Items recovered from a shipwreck, literally buried in the floor beneath the visitor’s feet and covered with transparent flooring, are less immediately visible. But as they tread carefully around this part of the exhibition, the visitor gets the sense of the maritime aspect of this trade, as well as its precarious nature.

‘Innocent luxuries’?

Of course, there are dangers in relying on ‘commodity history’ to tell the story of

Europe’s Asian centuries.

43

The temptation for museums to display things that are immediately engaging and recognizable for audiences is all too obvious. What is more immediate or engaging than such things as tasty food, a popular drink, and comfortable clothes?

But museums need to be wary of lazy comparisons; the

39 Object number: BHC1873. See Bowen, McAleer, and Blyth, Monsoon Traders , pp. 47–9.

40 Object number: BHC1157. See Bowen, McAleer, and Blyth, Monsoon Traders , p. 115.

41 Pieter van der Merwe, ‘Huggins, William John (1781–1845)’, Oxford Dictionary of National

Biography , Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2012

[http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/14053] (accessed 23.11.2012).

42 Information from museum label, July 2012.

43 Gert J. Oostindie, ‘Squaring the circle: commemorating the VOC after 400 years’, Bijdragen tot de

Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 159:1 (2003), 135–61, p. 154.

Page 11 of 15

JM

2.12.2012 interpretative trap that presents eighteenth-century European trade with Asia as evidence of the manifestation of early globalization is as trite as it is anachronistic.

The final section of this paper argues that public histories of European trade with Asia cannot rely solely on consumer identification; rather, they need to challenge audiences to consider what is complex or different or unpalatable about the past.

Gert Oostindie has queried the decision to ‘celebrate’ (rather than

‘commemorate’) the four-hundredth anniversary of the establishment of the VOC.

44

His doubts about terminology, language and tone draw attention to the need to introduce and incorporate other elements of this history: a darker side that is not necessarily immediately apparent in displays of precious porcelain and fine fabrics.

The history of the European encounter with Asia, including the trade in commodities and goods, has not always been one of mutual benefit or symmetrical exchange. At the beginning of new parliamentary session in November 1772, William Burrell entreated each of the members present to ‘recollect, how intimately his fortune and estate, his comfort, and if I may so call them, his innocent luxuries, are connected with this vast object of trade’.

45

More bluntly, one recent commentator has referred to the history of the British East India Company as ‘material evidence of a punishing encounter, driven by a desire for the smell, taste, colour and texture of exotic stuffs and essences’.

46

The acknowledgement and representation of these issues, and their importance for twenty-first-century museum visitors, are important considerations in any museum treatment of this particular trading episode.

As scholars have noted, the transformation of the museum from reliquary to forum has forced curators, and everyone else involved in organising displays and exhibitions, to reassess their role as cultural custodians.

47

As their core functions include the advancement of understanding, knowledge and intellectual engagement, museums play an important role in public commemoration. But there has long been an awareness that museums are sites for contesting power and for defining (and redefining) ideas of ‘personal’ and ‘national’ identity. Their displays confer legitimacy on specific interpretations of history, and attribute significance to particular events.

As Phyllis Leffler reminds us:

History museums are mirrors both to the past and to the present. Through the processes of selection, organization, and presentation, curators create knowledge about the past and often help visitors rethink their assumptions.

The public nature of exhibitions frequently creates a stage for engaging contemporary tensions. Museums have become places of ideas and of intellectual conflict, increasingly responsive to public opinion. On both sides

44 Gert J. Oostindie, ‘Squaring the circle: commemorating the VOC after 400 years’, Bijdragen tot de

Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 159:1 (2003), 135–61, p. 144.

45 Quoted in P. J. Marshall, The Making and Unmaking of Empires: Britain, India, and America c.1750–1783 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), p. 200.

46 Peter Campbell, ‘At the British Library. Review of Trading Places: The East India Company and

Asia, 1600–1834 by Anthony Farrington’, London Review of Books 24 (2002), p.31.

47 Amy Henderson and Adrienne L. Kaeppler, ‘Introduction’, in Amy Henderson and Adrienne L.

Kaeppler (eds), Exhibiting Dilemmas: Issues of representation at the Smithsonian (Washington, DC:

Smithsonian Institution Press, 1997), pp. 1–14, pp. 1–2.

Page 12 of 15

JM

2.12.2012 of the Atlantic, museums, like the people they represent, have evolved to reflect new sensibilities.

48

One of the ways in which this might be achieved is through a more profound engagement with the histories lying behind individual objects. This might be accomplished by offering the multiple interpretations of objects, or perhaps by tracing individual ‘object biographies’.

49

For example, the interpretation of the Wolterbeek dinner service on display in Het Scheepvaartmuseum in Amsterdam quotes from the museum’s acquisition records. The service was presented to the museum in August

1934, and ‘according to family lore, [it was] given by the Sultan of Malacca in 1818 to Rear Admiral C. J. Wolterbeek, when he took the colony from the English’. The label text, however, problematizes this interpretation. Why, a subsequent text label asks, do the Sultan’s own initials not appear alongside the ‘CJW’ monogram. And the label casts doubt on the family ‘lore’ by observing that, were it true, ‘it is curious that the nothing about this in Wolterbeek’s own notes’. Perhaps, the label suggests,

Wolterbeek had the set made himself in China as a memento of his success in

Malacca. By complicating the story of the dinner service, and offering a number of explanations for understanding the context of its creation and presentation to

Wolterbeek, the interpretation poses broader questions about the writing of history and the remembering of the past. Who has the authority to interpret this particular history of European-Asian connections? Ultimately, the label leaves the question of the origin of the dinner service open: ‘Perhaps we may never know’.

50

As we have seen, ships carry much interpretative freight in the galleries and exhibitions dealing with European East India companies, and their trading activities.

The ‘ship’, as an object, is employed as a way of explaining the maritime world of the

East India companies, teasing out some of the complexities of that history, and highlighting some of the entanglements of European merchants in a wider Asian world. This may be seen in the portrait of one of the Wadia family, a family of Parsi shipbuilders based in Bombay.

51

In the portrait of Jamsetjee Bomanjee Wadia, on display in the Traders gallery in Greenwich, he exhibits the attributes of shipbuilding like some sort of Italian Renaissance saint.

52 But the painting also emphasizes the materiality of the ship: in the background, there is a ship on the stocks, waiting to be launched; in his right hand, Jamsetjee holds a technical drawing used in its construction; and the silver ruler in his belt (a gift from the East India Company) and the dividers in his left hand draw attention to the reliance of the East India Company and its commercial activities on Asian technology and expertise. So the ship can be

48 Phyllis Leffler, ‘Peopling the Portholes: National identity and maritime museums in the U.S. and

U.K.’, The Public Historian 26:4 (2004), pp. 23–48, pp. 23–24.

49 For more on this approach, see Igor Kopytoff, ‘The cultural biography of things: commoditization as process’, in Arjun Appadurai (ed.), The Social Life of Things: Commodities in cultural perspective

(Cambridge, 1986), pp. 64–91; Appadurai, ‘Introduction: commodities and the politics of value’, in

Appadurai (ed.), The Social Life of Things, pp. 3–63.

50 Information from museum object labels, September 2012.

51 For further information, see Anne Bulley, ‘Wadia family ( per. c.

1730–1893)’, Oxford Dictionary of

National Biography , Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2010

[http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/69064] (accessed 23.11.2012).

52 Object number: BHC2803. See Bowen, McAleer, and Blyth, Monsoon Traders , pp. 113–14.

Page 13 of 15

JM

2.12.2012 used to convey a much wider story: one of the key points about the East India

Company is that it quickly became an Asian trader – embedding itself into Asian commercial networks and relying on Asians as much as Europeans for its commercial success. And this image fulfils that purpose, and powerfully conveys that message.

Conclusions: The future of the past

With the decline of European empires following the Second World War, the changing demographics of British society, and, more recently, the rise of India and China as global economic powers, the relevance of European East India companies and their trade in Asian goods has become clearer than ever. The concerns of scholars, and the public more generally, in ‘border-crossing, globalization, and comparative, regional and transnational history’ has also contributed to an upsurge of interest in this episode of global history.

53

A recent and powerful illustration of this trend may be seen in an exhibition of ‘goods from the East’ current on display in Beijing. Passion for

Porcelain opened in the National Museum of China in June 2012. Running for six months, it brought together 148 ‘exquisite’ pieces of porcelain from the British

Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum. The material on display focused on export porcelain, and the ensuing commercial and cultural links this trade forged. In common with many of the Western museums discussed above, the exhibition sought to highlight the mutual influence of this exchange on both the Chinese porcelainmaking industry and the social customs of the West.

54

Chinese porcelain and its interaction with Western markets ‘served as an important tool in global communications’. But this example provides a new twist in the public history of this phenomenon, as goods from the East – which subsequently became museum objects collected, conserved and displayed in the West – now return to Asia as examples of common cultural inheritance and mutual influence. As one of the curators of the exhibition explained, ‘the theme is China’s export ceramics, the story of trade and cultural links between Europe and China’.

55

But one might go further and suggest, as

Rosie Goldsmith does, that the exhibition is also ‘about flexing British-Chinese cultural-diplomatic muscle’: it is, in the words of Martin Roth, Director of the V&A, a

‘cultural political’ event.

56

The inherently transnational scope and impact of the history of the European

East India companies is a story for our time. As Philip Lawson observes, these corporate behemoths ‘represented a force for the globalization of trade and crosscultural contact before that phraseology became fashionable in our post-modern world’; they provide ‘a means of examining the links between the pre- and postindustrial worlds, and the movements of peoples and products that characterized the

53 Philip J. Stern, ‘History and historiography of the English East India Company: past, present, and future!’, History Compass 7:4 (2009), p. 1148.

54 See http://en.chnmuseum.cn/tabid/520/Default.aspx?ExhibitionLanguageID=241 (accessed

23.11.2012).

55 Quoted in Rosie Goldsmith, ‘Homecoming heroes’, Financial Times , 27 July 2012.

56 Ibid.

Page 14 of 15

JM

2.12.2012 whole dynamic’ of European expansionism.

57

The goods from the East that they brought back to Europe help to tell these histories. In Passion for Porcelain , for example, ‘every candlestick, jar, bowl, tankard, figurine, bottle, teapot, vase and dish here tells a story’.

58

To that end, therefore, it is important that public fora, such as museums, reflect the fundamental role played by European East India companies in building the modern world. It is also vital that they reflect the complexity of this history, insofar as the constraints of museum labels and exhibitions allow. Displays need to draw out both the contemporary parallels but also make clear that Europe’s

‘Asian centuries’ were a very particular period in global history.

57 Philip Lawson, The East India Company: A History (London: Longman, 1993), pp. 164, 165.

58 Rosie Goldsmith, ‘Homecoming heroes’, Financial Times , 27 July 2012.

Page 15 of 15