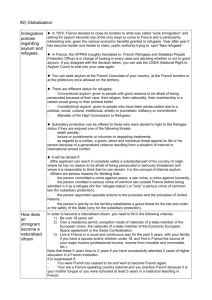

English - Europeanrights.eu

advertisement