IN THE THICK OF IT - ZAMBIA

by David Sefton

S

OME SUMMERS are more interesting than others. Then there is always that one summer, that

becomes the most memorable one of your life. Hunting with Werner Van Noordsdwyk gave me a

summer forever remembered. Werner is an incredible PH based in the Kafue region of Zambia. One

of his several camps is on a plain stretching out from the former King and Queen of England’s retreat,

their panoramic view teamed with wildlife in the 1950’s. My long-awaited hunt with Werner Van

Noordwyk had been scheduled for over a year. He is one of Africa’s top up-and-coming PH’s. I had

purchased his amazing donation at the Central Texas Safari Club Gala. My wife, a recognized professional

photographer, was there in Zambia to take pictures of Werner’s GMA and camp; I was there to hunt

buffalo.

Having had two bad buffalo hunts previously in Zim, I was spooked. The first day, we searched

and searched and just couldn’t find the legendary 1,000+ Kafue herd I had heard so much about. We kept

looking. The first day we stalked some, then covered many kilometers seeking fresh spoor, and just couldn’t

find the herds.

We left extra early the next morning. Ice for the first time in living memory had formed on the grass, and it

was bitterly cold in that early dawn. The buffalo once again were spooky, keeping their distance, and just

not where they were supposed to be. We found tracks, stalked, just couldn’t find them. They seemed to

disappear.

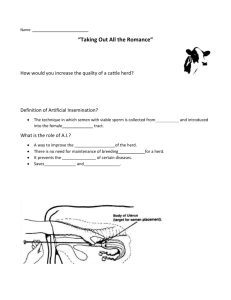

We circled the double hills again, decided to head back for a late lunch, and crossing the road were the

buffalo, exactly where we had spent hours earlier trying to

find them. They just streamed across, not noticing us. Over a

hundred passed the road. We were trapped. If we moved,

they would notice and run. Magnificent boss after boss

crossed the road, my hunting dream, yet I couldn’t even

reach for my gun! I dared not move an inch lest I spook

them. Suddenly a cow stopped dead in her tracks, turned,

stared at us, gave a warning low, and the herd broke into a

dead run, not stopping for almost ¾ of a mile. Finally she

slowed, then lowered her head and grazed. We waited then

slowly bailed out stalking—it took us an hour to make

contact. We slowly edged on, passing many cows and

young males. We kept inching forward and finally came on

a great bossed bull, but the angle was wrong and the

distance far. Up we inched, slowly coming around a group

of three bushes, and then the bull we were after was just

ahead. Making the turn, a cow had set up to the far right,

intentionally turning against the herd sensing someone

following. Busted! We froze, she stared at us, we stared at

her, a warning snort and the herd ran for another mile. We

could see the dust roiling far in the distance. We recouped,

regrouped, then stalked further. It was hot and dry now. The

tsetse flies were a real nuisance, and we just moved on. For

no reason the herd bolted again. We were over 500 yards

away, so we just turned and headed back to the truck, disgusted. I had a long ride back to camp that night.

Something was different the next day, it just seemed crisper, I was more positive: the day before, I

had looked them in the eye; been close enough to shoot; been on the sticks—today just felt right. Later, in

the field, we drove far down the GMA, till we found where we thought yesterday’s herd had crossed the

road. The spoor was very fresh, but now we followed the herd into extremely thick brush. Within 50 yards

we had less than five yards visibility. It was extremely thick and slow going. We kept spooking the buffs up

ahead and could hear them gallop off. Finally in midafternoon we abandoned the losing game. The wind

just wouldn’t stay with us in the thick stuff.

We made a huge loop, jumping miles and miles ahead. It was now late into the afternoon, and

again we saw the herd crossing an opening. Werner made a strategic move, backing the truck way down

the path so the buff wouldn’t see us this time. There were a huge number of calfs and cows. We took a

chance and begin working up the trail. The first 500 yards or so, I saw maybe 50 cows, most with calfs. We

had fairly open cover, with a few bushy trees sporadically sprouting every twenty yards or so before the

belt of grass ended in some disturbingly thick bush. If we spooked them, they were going into cover so

thick we couldn’t follow. As we inched down the trail we passed several young bulls, then finally we came

on a big one. His horns easily measured 46 inches, but we couldn’t see the boss.

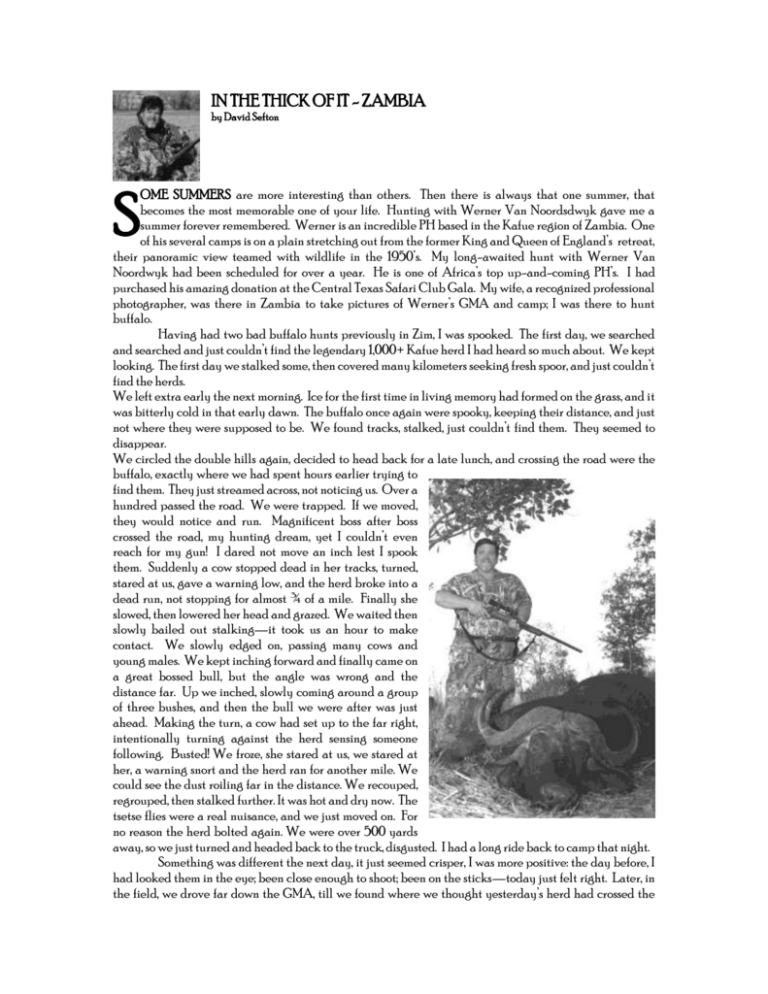

Slowly we crept up, sliding down the trail. The bull was feeding at an angle, and I set up on my

sticks. Finally he looked up and back so we had a good view of his boss. He was a big bull, but young, and

his boss was neither solid nor large. As trying as it was, I let him pass. We moved on, becoming aware we

were in the middle of a large elephant herd as well.

The babies were all around with the cow elephants. Due to the curve in the path I was less than ten

yards from large elephant cows. One tracker kept an eye on the elephants to the right, while Werner and I

kept focused on the buffalo to the left. We slid down the path, five of us moving as one, a human centipede,

creeping up on the nice old dagga boy. We set up, he wasn’t massively wide, but he appeared to have great

bosses. The sticks were out and up, I got ready, the light was failing. One of the hardest acts of self-control

was holding off my shot. Werner waited, and slowly the bull fed away but quartering. When he grazed

almost broadside at 60 or 70 yards, Werner whistled. The bull snapped his head around, showing his great

old scarred bosses. Werner hissed “Shoot.” I fired before he’d finished. My Barnes slammed the dagga boy

right through the shoulder. The old dagga boy launched himself up on two hoofs, straight up in the air,

pawing the sky. He paused, balancing before crashing to the ground. He staggered backwards for 10 or so

feet, then sagged to the grown.

The elephants surrounding us trumpeted wildly, crashing through the trees, over 200 head of buffalo

smashed through the bush in confusion. The moment was terse, tense and fraught with imminent danger. A

baby elephant screamed hysterically from behind the wounded buff and charged off across our path to his

mother. The elephants went wild, luckily charging away from us. We hadn’t seen the baby, and amazingly

he hadn’t been hit. The herd we thought was only 50 or so buffs was actually over 200, and they charged

to the left. We had animals running in all different directions, literally mayhem encircling us. It was a

madhouse and some minutes before everything calmed down.

After the crushing blow to my buffalo, he sagged to earth, stumbled backwards for ten-ish yards, and

slumped down, fighting death to his last breath. We stayed in place, frozen, till the mayhem settled itself,

and snuck up on the buffalo. I was cocked, loaded, off safety and ready to put another in him—unneeded,

because he was safely dead. In the gathering dusk we quickly created our trophy pictures. I was sure to

incorporate my killer new shooting sticks from African Creations. I mention them because they were so stiff

it was like shooting on a benchrest. They’ve truly engineered a better mousetrap! After the pictures we

loaded up the beast and headed to camp.

©2013 David Sefton, All Rights Reserved.

©2013 Photos by Leann Collins, All Rights Reserved