Life support syndrome

advertisement

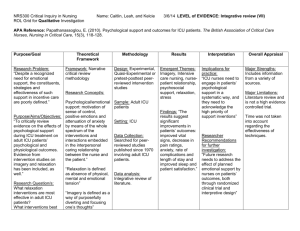

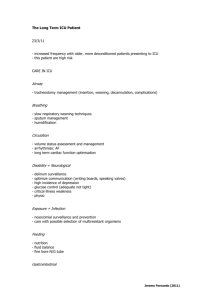

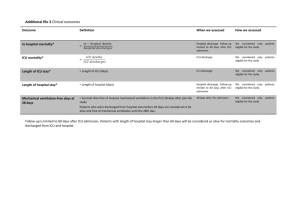

http://www.criticalillnessireland.com/life.php Life Support Syndrome/Psycho-affective disorder in intensive care units: a review Patients experience a range of psycho-affective disturbances that may be triggered by drugs, the environment, dehumanizing practices and sleep deprivation. Symptoms do not always disappear following discharge and further research is required to determine the long-term psychological effects of an ICU. Comprehensive assessment of the patient’s psychological state, using an appropriate tool, is necessary and should form an integral part of ongoing care. Interventions identified include eradication of dehumanizing behaviour, modification of environmental stimuli, effective communication and therapeutic touch. Where possible, communication needs should be addressed prior to admission, and patients and their families prepared for the unfamiliar world of the ICU. Introduction Florence Nightingale argued that the main function of the hospital is that it is should do no harm. However, in reality hospital environments, and specifically Intensive Care Units (ICUs), lead to patients experiencing a range of adverse psychological reactions which continue to cause distress for many months after discharge from hospital. The term ‘ICU syndrome’ was first framed in the 1960s to describe a range of psychological anomalies exhibited by some patients in ICUs. Other terms such as sensory deprivation, ICU psychosis, and ICUrelated post-traumatic stress disorder have all been applied, but appear to fall short of reflecting the alterations that occur in both mood and perception. The range of affective and psychotic phenomena that may be observed in practice on ICUs includes anxiety and fear, mild/severe psychosis with hallucinations, sleep disturbance and nightmares. In my clinical experience, many nurses recognize the existence of the ICU syndrome and its clinical features, but few appear confident in exploring the ‘lived experience’ of the syndrome with patients and their families. As the psychological trauma continues for patients for many months after discharge management of the syndrome is relevant for all concerned in care, not just the critical care team. ICU syndrome therefore remains an important topic for exploration. The following work defines ICU syndrome, and explores research and empirical evidence to describe the clinical features, contributory stressors, long-term effects and nursing interventions. The issues raised by an analysis of the literature are discussed and related to practice, concluding with future implications and recommendations. PSYCHOLOGICAL PHENOMENA Perceptual Difficulties The psychological effects of ICUs have been well documented and there are vivid accounts in the literature of the acute distress experienced by patients. Functional psychosis has been described, with reports of illusions, delirium, tactile and visual hallucinations, with delusions and disorientation. Midazolam, a benzodiazepine sedative, may cause particularly disturbing sexual hallucinations recalls the presence of gargoyles and witches during her time as a patient in intensive care. These impressions led to a fear of impending death and mistrust of ICU staff. In a study of 25 trauma patients all but three patients believed that they were being held captive, and 14 recalled attempting to escape. This study showed a surprisingly high percentage of patients remembering distressing delusional beliefs, which may have been a consequence of the initial insult and resultant post-traumatic stress experience. Studies of patients who have been in exceptionally threatening or catastrophic accidents have shown them to be particularly susceptible to prolonged psychological reactions. Although he incidence of ICU syndrome has been variably reported as 12.5—72% nurses often fail to recognize the patient’s psychotic experience until the patient becomes overtly agitated and deluded. This may be because of the patient’s inability to communicate verbally, and nurses’ inexperience in recognizing the non-verbal signs of psychosis. Whilst scoring systems for sedation and pain are integral elements of nursing care in an ICU, assessment of psychological needs is not formalized. Development of psychological assessment charts could allow early identification of perceptual disturbances and direct nurses consciously to address problems of mood and perception in care planning and in discussion with colleagues. It may be argued that nurses within ICUs are more comfortable in dealing with patients who exhibit confusion and disorientation than with the manifestations of psychosis. It is important to discuss with the patient their experience of perceptual disorder, and to emphasize the ‘normality’ of these experiences and their transient nature. If these issues are not addressed, then the patient is left isolated, in a world that is frightening and bizarre. AFFECTIVE DISORDER Anxiety, stress and despair are components of the ICU syndrome. Data has revealed patient memories of significant confusion and anxiety during the ‘twilight state’ between awareness and unconsciousness. The methodology was appropriate to the small sample size. Larger studies are often problematic, because of the limited size of an average ICU and the high mortality rates therein. As anxiety and fear become the overpowering responses to stress for ICU patients, their primary need is to feel secure. Unstructured interviews revealed that their overwhelming need was to feel safe. Family and friends, ICU staff and religious beliefs influenced positive feelings of security. Feelings of knowing and regaining control helped patients to hope and trust with confidence. CONFUSIONAL STATES Sedative drugs play a prominent role in the production of disorientation and perceptual disturbances. The number of patients receiving therapeutic paralysis is now relatively small, and sedation policies concentrate on achieving a lightly sedated, co-operative patient Sedation scoring is important for an accurate measurement of sedation levels, reducing the impact of drugrelated psychosis. Sedation tools offer different methods of assessing patients’ sedation levels: the Ramsey Scale, the Newcastle Sedation Scale and the Addenbrookes Sedation Scale are among the most widely used. A study of 100 ICU patients found that 41 patients remembered being confused and disorientated. Nurses, however, had only observed disorientation in five patients. Whilst this study was undertaken some years ago, few have attempted to repeat a large-scale examination of the psychological experience of ICU patients. These figures suggest that confusional states resulting from or coexisting with ICU syndrome may be grossly underestimated, even in today’s climate of increased awareness. Environmental cues such as pictures, calendars and newspapers are invaluable in reducing disorientation. However, the patient is often in a supine position, preventing observation of these orientating cues. The nurse therefore has an important role in providing reality orientation through frequent reminders of time, place and person. PATTERNS OF CHANGE The nature of psychological changes experienced by patients may follow a distinct pattern. Certain studies have reported a lucid period of 2—3 days preceding the development of the syndrome, which then characteristically starts on the third to seventh day in an ICU. The validity of these findings may be questioned, as the nature of critical illness often requires a period of sedation and ventilation for the first 72 hours of stay, making it virtually impossible to verify lucidity. The pattern of psychological change starts with a reduction in cognitive ability. Anxiety, disorientation and nightmares may then trigger a spiral into psychosis that can be severe, with the exhibition of anger, fear and hallucinatory responses. Depression often occurs at a time when physiological problems are approaching resolution and psychological well-being then only returns on discharge from the ICU. Stressors SENSORY INPUT A number of contributory stressors have been assigned to the development of ICU syndrome. Sensory deprivation has been recognized, and has been defined as a reduction in the quality or quantity of sensory input. Five types of alteration in sensory input, which may lead to abnormal behaviour, have been identified: an absolute reduction in the amount and variety of stimuli, little variation in stimuli, excessive noise, physical and social isolation, and restriction of movement. NOISE The noise and pace of ICUs are significant stressors for patients. Contributory factors are inappropriate alarm settings, suction equipment left on after use and telephones. As monitor and ventilator alarms contribute largely to high noise levels, consideration should be given to setting realistic physiological parameters, and then resetting these as the patient’s condition changes. Staff conversations have been regarded as a significant source of noise and confusion for patients. Personal discourse provides fertile ground for misinterpretation in semiconscious patients. Nursing and medical staff often fail to acknowledge a sedated patient’s presence when discussing physiological condition and treatment plans. When patients are not overtly aware, there may be comment on their poor prognosis at the bedside, increasing their fear of impending death and debility. As it is not possible positively to assess a patient’s level of awareness, patients may be ‘locked in’ with the fears and anxieties resulting from partially understood conversations. Patients surveyed 6 months after being in ICU remembered hearing bits and pieces of conversation during bedside ward rounds, which led to misinformation and fear and contributed to persecutory delusions. Consultant ward rounds normally include considerable numbers of staff at the bedside. A sedated patient is then subjected to increased and unexplained noise levels and activity.. PAIN Pain is a great area of concern for patients. Nurses are not good at judging the incidence or severity of pain, and studies of ICU patients report that pain is rated as the greatest stressor experienced. In a study surveying the views of 100 discharged ICU patients explored the stressors in an ICU. Forty-four percent of patients reported tracheal suctioning as the most unpleasant experience, and 48% arterial blood gas sampling. Both of these events were significant because of their association with pain. This work produced findings that may be generalized, as the researchers were careful not only to select a sample from a wide range of religious, occupational and educational groups, but also those who had a variable diagnosis. The presence of an endotracheal tube can be very distressing for patients, particularly during suction and changing position. The numerous invasive procedures the patient endures create a situation where there is not only frequent pain, but also the fear and expectation of pain. The patient may then come to associate the nurse’s touch with the presence of pain, leading to increasing levels of panic and paranoia. Many aspects of care and treatment proved to be painful: intubation; being turned; physical restrictions caused by machinery; suctioning; coughing; invasive procedures; gastro-intestinal disturbances caused by fluid management and physiotherapy. As a consequence of experiencing constant pain, the patient reported the need for more sedation. COMMUNICATION Verbal communication is often impossible for patients in ICUs, because of the presence of an endotracheal or tracheostomy tube. Non-verbal attempts to communicate are frequently unsuccessful, causing patients to feel frustration, depersonalization and insecurity. When nurses attempt to lip-read, frustration increases as the message is often misinterpreted, and attempts to write may fail because of fatigue, poor vision, hand tremors and the recumbent position Surveys have found that many intubated patients studied exhibited anxiety at being unable to speak, the inability to interact in any meaningful way ultimately leading to feelings of deprivation and isolation. It is hardly surprising that patients create a delusional world for their psychological survival when they cannot participate in a reality that is incomprehensible. A patient’s mental state appears to recover when verbal communication is restored. Mood and lucidity often improve when speaking valves are used with tracheostomy tubes, illustrating the importance of verbal communication to mental health. The quality of nurses’ contact with unresponsive patients is often poor. There is evidence that communication with patients is purely task-focused and concentrates on physical procedures. The average time spent in verbal communication was only 5% of the total care time. Information-giving and general reassurances (‘Try not to worry’) were the main categories of verbal communication observed. Deeper levels of interaction were also reported and included an explanation of the rationale for a procedure, with a reassurance of the expected sensation and a deeper display of awareness of the patient’s understanding when nurses reported phone enquiries to their patients. Further exploration of these issues might reveal whether junior nurses lack sufficient knowledge to communicate effectively, or whether long association with the culture of the ICU produces the procedural approach to interaction. Both studies, however, arguably reflect the task-orientated approach to communication which may be observed in the ICU. Effective communication is essential, and frequent explanations should be given to patients about their condition and care activities. Holistic care should lead nurses to communicate with patients at times when procedures are not being carried out and should address personal matters, orientation and provide a link with the outside world. Elective admission patients can be given information about the environment, possible equipment that may be used to monitor and administer treatment, and probable length of stay. If postoperative treatment includes the creation of a tracheostomy, then teaching lip reading techniques is essential. PHYSIOLOGICAL FACTORS Physiological disturbances such as hypotension, hypoxia and pyrexia may produce delirium, with resultant illusions, delusions and disorientation. The exclusion of psychological and environmental contributory factors to the development of ICU syndrome appear simplistic in the extreme. Such an approach excludes the impact that an individual’s interaction with the environment has on mental state. This may reflect the physiological bias towards health that may exist in an area of technological excellence. Induction of new staff to ICUs usually concentrates on instruction in the urgency of responding to physiological crisis but, as it is not seen as life-threatening, little attention is paid to acute psychological disturbance. The culture of physiological bias is therefore perpetuated with each generation of nurses. SLEEP DEPRIVATION Sleep deprivation has been explored in both laboratory conditions and in the clinical area. Symptoms of sleep deprivation have been shown to be restlessness, disorientation, combativeness, delusions, hallucinations, anxiety and increased illness. The unvarying 24-hour routine of an ICU means that patients may be unable to distinguish night from day. Small or blacked out windows, with continuous artificial lighting of a constant strength, remove natural cues to circadian rhythms. Perceptual disturbances, proximity of staff and unnecessary nursing interventions carried on throughout the night lead to interrupted sleep of poor quality. The legacy of ICU The long-term psychological effects of the ICU are less well-documented. The studies that have been carried out show the emergence of certain psychosocial problems: personality changes, loss of social skills, sexual dysfunction and altered body image. It has been asserted that many patients fail to recollect their experiences in the ICU. This may be only partially correct as for many patients the emotional essence of the episode remains long after discharge from hospital. Patients continue to suffer nightmares and sleep deprivation for years following a critical illness. In a survey carried out with 46 ICU patients following discharge, 46% contacted after a mean of 8 months reported sleep disturbance and ICU-related dreams. Flashbacks are a common theme recurring in studies. Post-traumatic stress disorder is characterized by flashbacks, recurrent nightmares, emotional numbing, hyper vigilance and avoidance of the original trauma. Studies of patients who have been in exceptionally threatening or catastrophic accidents have shown them to be particularly susceptible to prolonged psychological reactions such as post-traumatic stress disorder. Long-term research into the psychological experience of critically ill patients confirms that they are vulnerable to phobic anxiety states which, has implications for their ability to reintegrate into family life, employment and social groups. Further research is required into the long-term effects of ICU syndrome. Patients, who return to the unit following discharge, are a valuable source of action research. Personal experience of follow-up visits has revealed that patients remember believing they were imprisoned, fearing that their fate was certain death at the hands of their captors. Unfortunately, as avoidance of the fear-provoking stimulus is characteristic of post-traumatic stress disorder, patients who have phobic anxiety relating to the ICU are unlikely to participate in related research or to revisit the ICU through choice. This may partially explain the scarcity of data on the long-term effects of the ICU. Recommendations for Practise THERAPEUTIC USE OF SELF Nurses can reveal compassion and empathy by a therapeutic presence. Attentiveness and expressive touch manifest this use of self as a therapeutic tool. Expressive touch can enhance communication with a sedated patient. This may be defined as touch not related to a particular procedure, but gentle touch to socially acceptable areas of the patient’s body, which is spontaneous and affective. Touch has a comforting and calming effect on patients found that hospitalized patients reported a nurse’s touch as valued and thought that the touch personalized care. The simple act of holding a patient’s hand during medical procedures bridges the technical and human dimensions of critical care. Human warmth can be conveyed not only with words, but also with such non-verbal cues such as tone of voice and touch. If nurses only touch patients when performing procedures, then the presence of the nurse becomes synonymous with pain. RELATIVES Relatives and friends are a support in sustaining orientation and inclusion and should be valued as a resource in preventing ICU syndrome. Human beings provide an important part of the sensory environment for most patients but are often restricted in visiting time because of nursing and medical interventions. Rules governing visiting times may be of more benefit to staff and the smooth running of the ICU than they are to patients and their need for meaningful sensory input. More flexible visitor policies should therefore be considered. ONGOING SUPPORT There is little evidence that follow-up care and support are available for ICU patients. An initial period of ward liaison work by ICU staff could follow patients’ progress to wards to monitor psychosocial recovery. On discharge from an ICU, patients may seem lucid and able to process information given about illness. However, thoughts about the ICU and the nature of the critical illness suffered may be coloured by memories of delusions and hallucinations. Confrontation through discussion about memories of the ICU allows patients to build up a comprehensive picture, where rational explanation may be exchanged for fearful and chaotic memories. This process may be achieved through reminiscence therapy, which is a process of recalling forgotten experiences through verbal interaction between the person eliciting memories and one or more others. COMMUNITY CARE When patients are discharged home, they may experience a range of psychological and social problems. Early explanation about the consequences of illness and ICU should be explored with them and their supporters. Patients should be offered a discharge booklet, outlining possible difficulties that might be experienced during recovery and reinforcing the normality of delusional beliefs. Hospital discharge should involve a patient’s GP, who may then monitor ongoing physical and psychological problems and refer patients and their families for counselling if desired. Revisiting the ICU may be helpful for some patients and relatives, who may then have the opportunity to discuss experiences. Feedback raises awareness of patients’ perceptions of critical care and the performance of staff. Conclusion ICU syndrome remains prevalent in today’s critical care units and is destructive to patients’ mental health both during treatment and after discharge. Patients experience a range of psycho-affective disturbances which may be triggered by drugs, the environment, dehumanizing practices and sleep deprivation. Symptoms do not always disappear following discharge and further research is required to determine the long-term psychological effects of the ICU. Comprehensive assessment of a patient’s psychological state, using an appropriate tool, is necessary and should form an integral part of ongoing care. Interventions identified include eradication of dehumanizing behaviour, modification of environmental stimuli, effective communication and expressive touch. Where possible, communication needs should be addressed prior to admission, and patients and their families prepared for the unfamiliar world of an ICU. Finally, little change will be made in approaches to psychological care until the technological imperative in an ICU is superseded by a more humanistic emphasis.