Anxiety Disorders rev handout - The University of Illinois Archives

advertisement

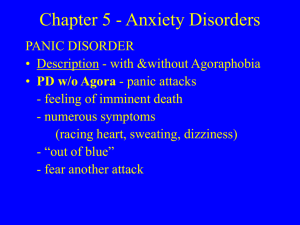

Drugs and Behavior: Session III Anxiety Disorders Sari Gilman Aronson, M.D. The Anxiety Disorders are a diverse group of psychiatric illnesses that have abnormal fear as their unifying characteristic. Anxiety as a symptom and Anxiety Disorders are common. 1015% of general medical outpatients and 10% of inpatients experiences significant anxiety. Of the healthy population, 25% of individuals are anxious at some time in their lives and 7.5% of these have a diagnosable anxiety disorder during a given month. Primary psychiatric disorders may be associated with anxiety, which may be prominent or even the presenting complaint. About 70% of depressed patients also have symptoms of anxiety and 20-30% of cases of anxiety disorder have an underlying depression. More specifically, 20% of depressed patients have panic attacks and 90% of patients with panic disorder become depressed. Depressed patients with a family history of anxiety are more likely to experience anxiety and depression than patients with a family history of depression alone. Anxiety may present as an early symptom of impending psychosis or an organic mental syndrome. The signs and symptoms of anxiety may be obvious or may be masked by physical and other psychological complaints. The psychological symptoms of anxiety are: apprehension, worry, fear and anticipation of misfortune; sense of doom or panic; hypervigilance; irritability; fatigue; insomnia; predisposition to accidents; derealization; depersonalization; and difficulty concentrating. The somatic complaints associated with anxiety are headache; dizziness and lightheadedness; palpitations and chest pain; upset stomach and diarrhea; frequent urination; lump in the throat; motor tension or restlessness, shortness of breath, paresthesias, and dry mouth. The physical signs of anxiety are diaphoresis; cool, clammy skin; tachycardia and arrhythmias; flushing and pallor; hyperreflexia, trembling; and easy startling and fidgeting. Symptoms of anxiety may mimic physical disease. In hyperventilation syndrome, a patient may complain of shortness of breath, weakness, paresthesias, headache, and carpopedal spasm. It is not uncommon for the patient to be completely unaware of the psychological stresses that led to the hyperventilation and deny feelings of anxiety. Symptoms and signs of anxiety are often associated with a wide variety of medical disease, sometimes before other signs become evident. Cardiovascular arteriosclerotic heart disease paroxysmal tachycardia mitral valve prolapse hyperdynamic beta-adrenergic circulatory state Pulmonary pulmonary embolism hypoxemia asthma chronic obstructive lung disease Endocrine and Metabolic hypoglycemia hyperthyroidism hypocalcemia Cushing's syndrome porphyria Tumors insulinoma carcinoid pheochromocytoma Neurologic multiple sclerosis temporal lobe epilepsy organic mental syndromes Meniere's disease Infections tuberculosis brucellosis Drug-related abstinence syndromes intoxications with sympathomimetics akathisia caffeinism MSG (Chinese restaurant syndrome) As you can see from the above discussion, symptoms of anxiety are very common in medical practice. Anxiety occurs as a symptom in other psychiatric illnesses (psychosis, mood disorders, etc.) and in many situations. Panic Disorder: DSM-IV Criteria Both of the following: 1. Recurrent and unexpected panic attacks 2. At least one of the attacks has been followed by 1 month or more of a. Persistent concern about having additional attacks b. Worry about the implication of the attack or its consequences (e.g. having a heart attack, “going crazy”) c. Significant change in behavior related to the attacks Not due to the direct physiological effects of a substance or a general medical condition. Agoraphobia may or may not be present Anxiety Disorders Case: Panic Disorder Connie is a 24-year-old graduate student in engineering who came for psychiatric evaluation and possible medication treatment at the urging of her psychotherapist. She said, “I feel terrible.” She had a 1-year history of problems that began with trouble sleeping. She woke up around 3 in the morning feeling sweaty, frightened, and short of breath. Connie though she may have had a nightmare, but couldn’t remember any dream content. About 8 months ago, she had a terrifying experience. She was driving her car on the freeway and began to feel pressure in her chest, shortness of breath, sweaty, and lightheaded, so she pulled her car over to the side of the road. Connie was terrified that she might be dying, and was worried that her asthma had gotten worse. Her boyfriend, Jason, called 911 on her cell phone. Connie was taken to the Emergency Department at a local hospital for evaluation. She felt better within 1 hour and was relieved that her physical examination, chest x-ray, EKG, and labs (including cardiac enzymes, hemoglobin, and TSH) were all normal. The physician told her to “take it easy…you may have had a panic attack”. Connie had about 10 more episodes like this over the ensuing 4 months. She stopped driving and began to feel frightened about going out of her apartment (although she did force herself to go to class). Jason was very kind, and spent time with her, encouraging her to not withdraw. Jason became very concerned about 8 weeks ago, when he thought Connie might be getting worse. She had episodes of crying, talked about the hopelessness of her situation and how she “could not go on like this”. Connie said she couldn’t eat, couldn’t concentrate on her work, didn’t feel like doing anything, and felt “totally worthless”. Jason suggested that she begin some counseling, which she started 4 weeks prior to her first psychiatric visit. Connie had never experienced anything like this before. She said she was always a bit shy and uncomfortable with new people, but never had these terrifying episodes of fear, and had never felt this badly before. She had always done well in school and was able to make friends and keep them. Her mother tended to be a “worrier”, and her maternal aunt had been treated for “nerves” at age 38. Her father’s father had a drinking problem, but stopped drinking when he was in his late 20s. Connie is the youngest of 3 children and grew up in what she described as a “very supportive and loving family”. She had talked with one of her sisters about how she had been feeling, and her sister decided to come for a visit “just so we can be together for a while”. Connie was very grateful. Connie was healthy except for a history of exercise-induced asthma and mild reactive airways. These problems were well managed by use of an albuterol inhaler prn. The inhaler did not help during her episodes. Mental Status Evaluation Connie was dressed in shorts and a T-shirt, and looked tired. She looked down throughout most of the interview, but did make eye contact with the examiner when she was describing her episodes. She fidgeted in the chair. Her speech was fluent and soft. Connie described her mood as “bad and scared”. Her affect showed apprehensiveness and thoughtfulness, but no tearfulness or irritability. She said she was “worried about everything, especially if I will be kicked out of graduate school”. Her thinking was logical yet she tended to see the negative side of issues. Although she could believe that she might feel better, she was worried that she would continue to “feel like this forever, and that I couldn’t take”. She denied hallucinations. She did not want to die or harm herself. Her cognitive functions were grossly intact with excellent memory. Her judgment and insight were good. Treatment Connie was started on nortriptyline at 25 mg hs. Her dose was gradually increased to 125 mg. She had 80% relief of symptoms: her panic attacks stopped, her baseline anxiety level decreased, her symptoms of depression improved, and she began to look forward to things in her life. However, she continued to have trouble concentrating and noted that her mood would drop around the time of her menses. Her nortriptyline blood level was 140 ng/ml. Lithium carbonate, 600 mg per day, was added. She had complete remission of symptoms within 3 weeks. Her lithium blood level was 0.5 meq/L. Connie stayed on medication and continued psychotherapy for 1 ½ years. She had to work diligently on her agoraphobia and fear of driving. During her treatment, her social anxiety was addressed as well. Questions and Discussion Points for Lecture 1. What psychiatric problem is Connie experiencing? Panic Disorder with subsequent Major Depression 2. What symptoms is Connie experiencing? a. 1 year history of problems b. nocturnal panic attacks c. daytime panic attacks d. agoraphobia e. driving phobia f. elevated baseline anxiety g. feeling down h. diminished appetite i. crying j. hopelessness k. feelings of worthlessness l. decreased concentration m. social withdrawal 3. What do we know about the neurobiology of this disorder? a. anatomical and functional brain imaging b. lactate and respiratory hypotheses c. noradrenergic hypothesis d. serotonergic hypothesis e. adenosinergic hypothesis f. benzodiazepine receptor sensitivity hypothesis g. hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysregulation h. sleep and panic disorder 4. What are the biological bases of Connie’s symptoms? a. autonomic nervous system dysregulation b. possible respiratory system sensitivity to lactate or CO2 c. serotonergic system dysregulation 5. What would be the features of a medication that would help with these problems a. alter autonomic nervous system response 1. increase threshold for central nervous system “panic button”: tricyclic antidepressants, perhaps serotonin reuptake inhibitors 2. decrease response to anxiety: benzodiazepines b. increase available serotonin (SSRIs such as paroxetine, sertraline) c. treat depression 6. What kind of psychotherapy is necessary for Connie to have a full recovery? behavioral therapy that deals directly with her agoraphobia and fear of driving. The Neurobiology of Anxiety Disorders Sari Gilman Aronson, M.D. References 1. Schatzberg AF, Nemeroff CB (Eds.), Textbook of Psychopharmacology, Second Edition. 1998, American Psychiatric Press, Inc., Washington, D.C. 2. Stoudemire A., Clinical Psychiatry for Medical Students, Third Edition. 1998. LippincottRaven Publishers, Philadelphia. Panic Disorder Panic disorder probably is a syndrome, a heterogeneous group of neuropathological diatheses (susceptibilities) rather than a singular biological phenomenon. The genetic basis for panic disorder is strongly suspected even though there has not been a linkage established to any particular gene. 1. Lactate and Respiratory Hypotheses: It had been observed clinically that chronically anxious patients had decreased exercise tolerance generating the idea that these individuals had an abnormality in lactate metabolism. In individuals with panic disorder, infusion of sodium lactate elicited panic attacks in 50-70% (controls 10%). Sodium lactate is a potent respiratory stimulant, increasing the respiratory rate. In addition to potentially abnormal responses to sodium lactate, almost all patients with panic disorder complain of shortness of breath during a panic attack. A variety of studies have revealed that patients with panic disorder may have a heightened behavioral sensitivity to and an irregular respiratory rhythm in response to carbon dioxide. Some investigators have proposed that patients with panic disorder have a biologically based hypersensitive respiratory control system believed to operate at the level of brain stem chemoreceptors. Other investigators consider patients with panic disorder to have a tendency to be frightened by and intolerant of the physical sensations of shortness of breath induced by either sodium lactate or carbon dioxide. For example, patients treated with cognitive-behavior therapy are less vulnerable to lactate-induced panic. The relationship of an abnormality in respiration to panic attacks is one of the most compelling and controversial theories presently being investigated. 2. Noradrenergic Hypothesis: This hypothesis postulates a dysregulation of the neurotransmitter norepinephrine. One of the major stimuli was identification of the locus ceruleus as the site of generation of anxiety-like behaviors in primates. Although there are data to support this hypothesis, significant criticisms have been made (Stein et al p. 611-612 in Textbook of Psychopharmacology: Second Edition). 3. Serotonergic Dysfunction Hypothesis: Serotonin dysfunction has been uncovered in nearly all the neuropsychiatric disorders (depression, schizophrenia, obsessivecompulsive disorder, alcoholism). Several studies have found that patients with panic disorder are sensitive to the anxiety producing effects of serotonin receptor stimulators (agonists). The role of serotonin is considered to be very important in understanding the biology of panic disorder. 4. Adenosinergic Dysfunction Hypothesis: Patients with panic disorder are hypersensitive to the anxiogenic effects of caffeine. Caffeine influences the adenosine receptor, a major neuromodulator in the brain, leading to the hypothesis that there is adenosinergic dysfunction in panic disorder. 5. Benzodiazepine Receptor Sensitivity Hypothesis: The gamma-amino butyric acid (GABA) -benzodiazepine receptor complex plays a central role in the mediation of anxiety. Altered benzodiazepine receptor sensitivity has been noted in patients with panic disorder. This may be an aspect of all anxiety disorders rather than a phenomenon specific to panic disorder. 6. Neuroendocrine Hypotheses: There is some evidence for a dysregulation of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis in panic disorder (a blunted growth hormone response to clonidine). Patients with the most severe panic may have more dysregulation. There is no evidence to support dysregulation of the HypothalamicPituitary-Thyroid (HPT) axis in patients with panic disorder. 7. Sleep and Panic Disorder: Most studies of sleep in patients with panic disorder show normal sleep architecture. There is significant interest in sleep panic attacks, which occur in the transition between stages 2 and 3 non-REM sleep (a time when dreaming is absent and cognitions are minimal). 8. Neuroimaging Studies: An asymmetry of cerebral blood flow to the hippocampus (left less than right hemisphere) has been noted by positron-emission tomography (PET scan). Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) Obsessive-compulsive disorder is a heterogeneous condition, most likely with different etiologies for different subtypes. 1. Autoimmune (post-streptococcal) hypothesis: Some children with Sydenham’s chorea (a complication of streptococcal infection and rheumatic fever) develop prominent obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Children who are more susceptible to development of rheumatic fever (as studied by looking for a specific protein on the membrane of a B lymphocyte white blood cell) may also be more susceptible to development of a poststreptococcal central nervous system syndrome, which manifests as obsessional in nature. Patients with childhood onset of obsessive-compulsive disorder, Tourette’s Disorder (a neurological syndrome characterized by motor or vocal tics, and variable obsessive-compulsive, attention-deficit, hyperactivity, and depressive symptoms), and chronic tic disorders showed the same susceptibility to development of rheumatic fever. If these data remain compelling, offering susceptible individuals either antibiotics for prevention or immunosuppressive agents for treatment may prove helpful. 2. Serotonergic Dysfunction: Obsessive-compulsive symptoms can be exacerbated by administration of a serotonin agonist (a compound that acts like serotonin) and blocked when the patient is pre-treated with an antiobsessional medication. This suggests that activation of the serotonergic system is involved in OCD. 3. Neuroanatomy and Neuroimaging: Many investigators have speculated the OCD is a disease of a deep portion of the brain called the striatum. This area contains many interconnections between the serotonergic, dopaminergic and adrenergic neurotransmitter systems. Functional neuroimaging studies have consistently reported differences in patients with OCD and controls in one or more regions that constitute the basal ganglia-thalamic-orbitofrontal-cortical circuitry, in particular the basal ganglia and medial prefrontal cortex. Function in these areas has normalized with either pharmacotherapy or behavior therapy. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Most of the studies in this area have investigated PTSD secondary to combat. Studies have demonstrated elevated blood pressure or heart rate in veterans with PTSD who are at rest or exposed to war imagery. In addition, an increased startle reactivity has been noted. 1. Adrenergic Dysfunction: Biochemical evidence of adrenergic hyperfunction has been only partially supportive and less robust than data from the psychophysiological studies. 2. Neuroendocrine Dysfunction: Male combat veterans with PTSD have differences in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis compared to healthy subjects. They showed lower plasma cortisol levels, much like that seen in Holocaust survivors. In contrast, female survivors of childhood sexual abuse showed elevated excretion of urinary cortisol (much like some patients with depression). There is some thought that all patients with PTSD may have an altered pituitary response to adrenal hormones. 3. Neurocognitive Dysfunction: Most studies have found some evidence of short-term explicit verbal memory dysfunction in patients with PTSD, with the nature and extent highly variable. Part of the variance may be due to alcohol dependence/abuse, and depression. Studies looking at the hippocampus, an area of the brain important in explicit memory systems and negatively affected by stress, have revealed decreased hippocampal volume. There has not been a consistent pattern to where the volume reduction has occurred. Social Phobia 1. Sympathetic Nervous System Function: One hypothesis has been that sympathetic nervous system function (the fight or flight system) might be overactive in patients with social phobia; however, studies have failed to consistently characterize any differences. There may be differential function between patients with generalized social phobia compared to those with a more discrete problem. 2. Neuroendocrine Function: There is little knowledge about the neuroendocrinology of social phobia compared to what is known about depressive disorders or panic disorder. 3. Monoaminergic Function: There may be some noradrenergic dysregulation in social phobia (a blunted growth hormone response to clonidine). One study has suggested that there may be an abnormality of the serotonin 2C receptor. 4. Neuroimaging: Data from single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) has suggested that patients with generalized social phobia had an abnormality in the dopamine system.