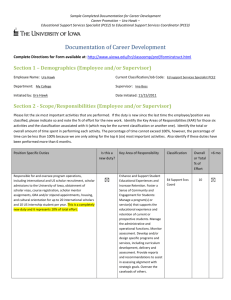

wanyaka_budgettaxation (Microsoft Word Document)

advertisement