Library assignment I - Faculty Homepages (homepage.smc.edu)

advertisement

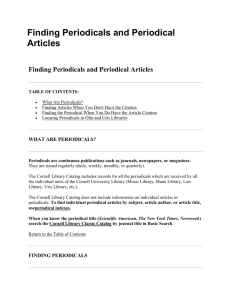

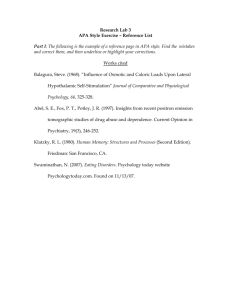

Bio21 Students: Below is an article to familiarize you with the general literature search method and more specifically, how to find scientific publications online or at SMC and UCLA. Please read the entire text and click on some of the links for further information and further use. If the link is dead, simply skip it. Formats of Library Resources Information in libraries comes in several different formats, which usually means it is presented, processed, shelved, and stored in several different ways. Books, for example, are usually shelved in specific areas, away from most issues of magazines, copies of videotapes, or microfilmed materials. If library researchers want to use a library to maximum effect, they should begin by finding out what materials are available there, and in what form; what clientele they were meant for; where materials are held in the library; how to use library tools to access them; and how to utilize the materials effectively. Library materials include print and non-print formats. The formats have evolved from primarily print materials, such as books and periodicals, to include multi-media materials (e. g. videotapes, audiocassettes, slides) and, more recently, electronic resources such as discs and Internet-based databases. No matter what the format of the information happens to be, however, it always has to be made accessible to the researcher. Accessibility is usually achieved in one or more of four major ways, or access points: by who wrote or compiled it (author); by what it is named (title); by what it is about (subject); or by an important word or words that appear somewhere in the document (keyword). Formerly, before widespread digitalization of library materials, the “group-concept” access points of authors, titles, or subjects were virtually the only access points. Then computers made it possible to search by a key word or words instead of by a group concept. Keyword searching allows for searching by one or more meaningful words, in documents of sometimes many thousands of words, in the hope of making the search more specific and customized, and therefore more likely to produce the desired results. Libraries have books, periodicals, multi-media, and electronic materials. Some are in print or electronic form, or on storage material such as microfilm. Because of their different forms, natures, and intended uses they are usually shelved separately and sometimes accessed separately. Today, most libraries have much of their materials in print, media, and electronic format. Sometimes beginning library researchers confuse the function of a library resource or tool with its format. This is understandable, but it gets in the way of efficient searching. A library resource or tool’s function is defined by its intended use and/or content. Materials and equipment in a library include both information resources, and the tools used to access them. Books and periodicals (magazines, newspapers, and journals) are the mainstays of most libraries, and library users are all used to seeing them in their customary paper formats. But some books are on audiocassette or in computer form. Some periodical issues are also in electronic form, or on microfilm. Yet these items are no less books or periodicals because they are not in paper form. The library tools used to access library materials or information about them can also be in different forms. The reference tool in libraries which helps users locate books is a catalog. It doesn’t matter if it is in card, book, or computer form; if its job is to tell users which books the library owns, and where they are located, the resource is a catalog. Similarly, a library reference tool called an index allows users to search for periodical articles on wanted topics. Indexes specify exactly which issues of periodicals, with dates and page numbers, contain articles on a given subject. It doesn’t matter if the index is in book or computer format, it is an index because of the function it performs. Many library users fall into the trap of defining a tool or resource by only a quick glance at its format, instead of looking to see which function it performs. Take the time, as you begin research in a library, to find out which resources are available and where they are located. Begin with finding the two most constant access tools in libraries, the catalogs and the indexes, which respectively tell researchers how to find books and periodical articles. 1 Flow of Information http://guides.library.ucla.edu/start The flow of information is a conceptual timeline of how information is created, disseminated, and found. Information is dispersed through a variety of channels. Depending on the type of information, the time it takes to reach its audience could range from seconds to minutes, days to weeks, or months to years. Knowing how information flows helps you understand what types of information you need and how to search and obtain the targeted information. Report of Event News (Internet / TV / Radio Services) Time Frame Seconds/Minutes Newspapers (print) Day / Days+ Magazines (print) Week / Weeks Journals (print) Electronic Journals 6 months + 3 months + Books 2 years + E-books, Digitized Books 2 years + Reference Sources Average 10 years Where to look Websites TV news indexes Online newspaper websites Newspaper indexes Periodical indexes Library catalog Library catalog Article database Journal website Google Scholar Library catalog Library catalog Digital collections Library catalog Written by Journalists Audience General public Professional journalists General public Professional journalists, poets, writers of fiction, and essayists General public to knowledgeable layperson Scholars, specialists, and students Specialists in the field, usually scholars with PhDs Specialists/scholars Specialists/scholars Specialists/scholars Web Pages Seconds/minutes to Web search Anyone years tools A Look at Linear Time and Information: 1. from the occurrence of an event, era, social movement or discovery 2. to the documentation of evidence relating to this event, era, social movement, etc. 3. to how the evidence is disseminated 4. and how researchers (and term paper writers) can find this documentation General public to specialists General public to specialists General public to specialists General public to Specialists Books Books and periodicals still comprise the main kinds of print materials in most libraries. Access to information in or about printed books is afforded through a library’s catalog. Every library has one: it could be a card, book, or computer catalog, though most contemporary libraries now have the latter type. The SMC Library Catalog is a computer catalog, or OPAC (Online Public Access Catalog). The principal job of a library catalog is to tell the library user which materials the library owns, where they are located, and how they are made available. Typical library holdings listed in catalogs include books, periodicals, media materials, and other items the library owns. In most libraries, books are placed on bookshelves, which are often called stacks, by subject areas. These areas are coded according to a formal classification system. A classification system is a standardized set of rules for labeling and identifying books according to their subjects, authors and other distinguishing information. Each book is given a call number, which is the code that represents: the classification system used; the subject, author, and/or title of the book; and further identifying information. It also serves as the “address” for placing and locating the book on library shelves. 2 The two major classification systems used in libraries in the United States are the Dewey Decimal Classification System (DDC), used by most public libraries, and the Library of Congress Classification System (LC), used by most college, university, and research libraries. Another important classification system for health-science students to know is the National Library of Medicine Classification System (NLM), created by the National Institute of Health’s National Library of Medicine, and mainly used by major health sciences collections such as UCLA’s Biomedical Library. In each of these systems a set of numbers, a set of letters of the alphabet, or configurations of both stand for subject areas. In Dewey libraries, books on mathematics and science are placed in the 500 section. Specific sciences are given specific areas within the 500s range. Human Anatomy and other biology books, for example, are in the 570s area. The same book in an LC library, where works on mathematics and science are in the Q’s, would be in section QM, since those are the call letters for works on Human Anatomy. And in an NLM library, the same book would be in section QS. Books are placed on bookshelves by subject, and beginning researchers might think that the fastest way to find what they need is to simply go directly to (for example) the science section and browse there to see what was available. Using this method might net one or useful books. But this kind of hit-or-miss research rarely suits the purposes of serious students, scholars, and other researchers. They need the most proficient, specific, and time-saving means possible to locate needed information to write their papers or study for exams. So they have to take the time before beginning research to learn the ways of efficiently accessing the information they need. Using the catalog is the most efficient way to zero in on needed books. The listing for each book in the catalog is called the record (or entry) for the book. The record or entry gives not only the call number, but also other important identifying and describing information, such as author, title, city of publication, the publisher, and the copyright or publication date of the book. These basic components of a book’s description usually comprise a basic citation for the book, because they include the most fundamental descriptions needed to identify or describe accurately a specific book. Citations are useful for both locating materials and for documenting them in notes and bibliographies. Citations are standardized according to a set of rules called a style, which dictates how entries are arranged, put in order, punctuated, and written out. There are many styles that students use in completing their academic research compositions. Two of the ones most widely used in colleges and universities are the MLA (Modern Language Association) and the APA (American Psychological Association) styles. There are also other widely-used styles. Professors usually choose one and instruct their students to use it when writing required papers. Tips for Book Searching http://guides.library.ucla.edu/content.php?pid=60895&sid=2754381 When searching for books in the UCLA Library Catalog, here are a few strategies to start with: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. If you are not sure of where to start, do a Keyword search for relevant terms or phrases (put the phrases in "quotation marks") If you already have a relevant book or article in hand, use its bibliography to find other sources on the same topic If you have the title of the book you want, do a Title (start of) search to find the call number If you find a useful title, click on the Subject(s): to get a list of subject headings that will lead to other books on the same topic Use quotation marks if you want to search a phrase Use ? to truncate a word, e.g., american? will retrieve american and americans Selected E-book Collections HathiTrust Digital Library. http://www.hathitrust.org/home HathiTrust Digital Library provides full-text access to millions of items in the public domain and partial access to material still in copyright from a variety of sources, including the University of California libraries, one of the founders of the HathiTrust. Digitized material can be searched like a traditional library catalog or for words that occur within the items. UC Press E-Books Collection, 1982-2004 http://publishing.cdlib.org/ucpressebooks/ Almost 2,000 books from academic presses on a range of topics, including art, science, history, music, religion, and fiction. Access to the entire collection of electronic books is open to all University of California faculty, staff, and students, while more than 500 of the titles are available to the public. Print versions of many of the electronic books can be purchased directly from the publishers. 3 Encyclopedias Major Online Encyclopedias http://guides.library.ucla.edu/content.php?pid=44446&sid=328962 The links below lead you to encyclopedia and dictionary titles that come from major vendors of online reference tools. These resources are primarily for humanities and social sciences. For biological and physical sciences, see the appropriate research guides for those disciplines. The Problem with Wikipedia Andrew Raff April 19, 2006 Jason Scott recently gave a talk about The Great Failure of Wikipedia. The audio is available at the Internet Arcive: The Great Failure of Wikipedia (April 8, 2006). Scott uses specific examples to discuss the problems that face Wikipedia. Despite the appearance of veracity and authority, Wikipedia faces significant challenges before it embodies "the availability of the sum of human knowledge to everyone on Earth for free." Wikipedia remains a great place to be an information tourist, but falls short as a serious information resource . The antiexpert bias that Scott notes in the Wikipedia editorial process will continue to keep the actual Wikipedia from becoming anything more than a novelty for information professionals. In the NY Times, Randall Stross writes: Anonymous Source Is Not the Same as Open Source "Wikipedia, the free online encyclopedia, currently serves up the following: Five billion pages a month. More than 120 languages. In excess of one million English-language articles. And a single nagging epistemological question: Can an article be judged as credible without knowing its author? Wikipedia says yes, but I am unconvinced." At Concurring Opinions, Laura Heymann notes a case in the US Court of Federal Claims that discussed the reliability and admissibility of Wikipedia articles:Concurring Opinions: Wikipedia in the Courts: "In an opinion released in February, the U.S. Court of Federal Claims scolded a special master in a vaccine injury case for sua sponte supplementing the record with ‘medical ‘articles’ on afebrile seizures’ that she located on the Internet." Lore Sjöberg, Wired: The Wikipedia FAQK: "The Wikipedia philosophy can be summed up thusly: 'Experts are scum.'" danah boyd offers some insight on the Wikipedia editorial process: on being notable in Wikipedia: "People wanted "proof" that i was notable; they wanted proof of every aspect of my profile. Then, when people in my field stood up for my entry in the discussion for deletion, they were attacked for not being Wikipedians." Do any readers have academic Lexis/Westlaw or Hein access? Could you run a search to see if any law review articles cite to wikipedia, and if so, how many? Previously: Wikipedia Woes, Wikipedia and Authority (edited 4/24 to add Concurring Opinions, NYT and Wired links) Posted by Andrew Raff on April 19, 2006 11:02 PM | Permalink Periodicals and Periodical Indexes Access to information in periodicals (magazines, newspapers, and journals) is provided by indexes (or indices). A periodical index differs from a catalog, which is usually set up by each library to reflect only what that specific library or library system owns. Indexes, however, are generally published by outside companies who choose which periodicals they feature, and who then sell their indexes to libraries on a subscription basis. Generally, libraries don’t have a direct voice in selecting the periodicals that the companies use. Therefore, though a library might subscribe to a particular index, such as General Science Index, the library probably won’t own all the journals and magazines used in the index. Indexes allow users to look up a subject and discover exactly which issues of periodicals have articles on that topic. The topic listings under which the articles are found are called subject headings. Searching in this way eliminates aimless browsing, guessing, and loss of valuable time. Indexes customarily provide the title of each article, its author’s), the title of the periodical in which the article appears, the date of the periodical and the volume, issue, and page numbers of the article. This information comprises a basic citation for an article. The citation includes the most fundamental descriptions needed to identify accurately a specific article, just as similar appropriate information identifies a book. A correct periodical citation enables researchers to check their library’s holdings to find out whether the library owns the needed periodical and issue, whether in electronic or print form. If so, researchers can then retrieve the issue and find the article. Indexes that include summaries of the articles as well as citations are called “abstracts”. Biological Abstracts, for example, is an abstract and one of the most useful titles for biology students. 4 Electronic Resources Most SMC Library books and periodicals are still in print format. So are some of our indexes to periodical articles. But, in keeping with most other libraries, SMC makes considered but timely transitions from traditional formats to electronic ones as often as feasible. This is because of the greater capacity for speed, specificity, and efficiency that electronic resources offer library users. Digitized resources such as periodical indexes on CD-ROM (Compact Disc Read-Only Memory) were the forerunners of online databases that now come to us via the Internet. Online indexes are web-based resources, meaning that information comes through the World Wide Web and can be constantly added to, deleted, or updated at all hours of the day and night, making it immediately available in the databases. Researchers use a browser such as Google or Microsoft Internet Explorer for accessing materials on the Web. Web-based search engines and databases are usually searched by keywords connected, in a structured search, by the Boolean operators AND, OR, or NOT. Boolean searching is named for mathematician George Boole, and will be discussed more fully later in the tutorial. Web materials can be useful, but as with all other documents from all other sources, researchers have to evaluate each web site and web document critically. Since almost anyone with a computer can publish on the Web, the credentials of document creators cannot be easily verified. Finding documents through the Internet does not give the documents automatic authority. There are, however, several web sites that offer good advice on how to evaluate Internet sources. Here is one from Cornell and another from UCLA. The SMC Library’s catalog/OPAC and several of the Library’s academic databases are Web-based. The OPAC represents an electronic form of a print card catalog. The databases can also represent electronic versions of print indexes or other reference sources. These databases are proprietary and not found for free on the Internet. The Library subscribes to these resources just as it subscribes to print versions of, for example, the Los Angeles Times, so that students will have appropriate and useful information available to them that is targeted to their general needs. The databases are accessed on computer workstations, but although they come to us via the World Wide Web they are not strictly Internet documents. Books, Periodicals, and Periodical Indexes Books and the OPAC SMC Library uses a web-based Online Public Access Catalog, or OPAC, to inform users about the books and other materials in the Library’s collections, and to tell where these materials are located. The Library provides computer workstations that allow users to search online for materials such as books and periodical titles through the catalog, periodical articles through the databases, and Internet documents through the World Wide Web. Users need to access the Library Home Page, which displays gateway access points for performing these searches. Starting from the Library Home Page, follow basic instructions for using the Library Catalog as well as others onscreen to find out which books, periodical and media titles that the SMC Library owns, as well as to locate reserve materials set aside by instructors for their classes. Analyzing OPAC Records To search for and retrieve materials efficiently, Library users should be able to identify and understand component parts of records found through the SMC Library OPAC. A typical SMC Library OPAC record is illustrated below, with identification/explanation of its components following. Use the identifications and explanations provided below the record as a guide to answer the questions in Quiz 2. QR41.2 .T67 2001 Microbiology: an introduction Tortora, Gerard J. Personal Author: Title: Edition: Publication info: Physical descript: General Note: Held by: Subject term: Added author: Added author: Tortora, Gerard J. Microbiology : an introduction / Gerard J. Tortora, Berdell R. Funke, Christine L. Case. 7th ed. San Francisco : Benjamin Cummings, c2001. xxiv, 887 p. : ill. (chiefly col.) ; 29 cm. Includes index. MAIN Microbiology. Funke, Berdell R. Case, Christine L., 1948- 5 Copy Holds Location Call Numbers for: MAIN 1) QR41.2 .T67 2001 1 NONE RESERVES desk:RESERVES / circ rule:RESRV_2HR 2 NONE RESERVES desk:RESERVES / circ rule:RESRV_2HR Call Number of the Book: QR41.2.T67 2001 Indicates the LC subject/identification code for the book Personal Author(s): Gerard J. Tortora, Berdell R. Funke, Christine L. Case Gives the names of the person(s) who wrote the book. Title: Microbiology: An Introduction The name of the book. Edition of the book: 7th ed. Indicates how many times the original text of this specific book was revised or updated, up to and including this specific edition; and which revision or update this particular book represents. Publication Info: San Francisco, Benjamin Cummings, c2001 Tells the city where the book was published; the name of the publisher of the book; and the copyright date of the book Physical Description of the book: xxiv, 887p.: ill. (chiefly col); 29cm Describes the number of preliminary pages (xxiv); of text pages (887); illustrations (chiefly illustrations in color); and height of the book (29 centimeters) Held by: MAIN Indicates the building where the book is kept: i.e., the SMC Library building Subject term: Microbiology Gives the subject of the book and the subject heading under which this book can be found in the OPAC Added Author: Funke, Berdell R., and Case, Christine L. Gives the names of other persons who co-wrote the book Copy: 1 and 2 Indicates how many copies of the book the Library owns and locating information for each copy Holds: NONE Tells whether there has been a formal request by a Library user to hold a checked-out book for that user when it is returned; and also tells how many hold requests have been made. “NONE” means that no requests for holds have been made for the book, so it should be available. Location: RESERVES Tells whether the book is in the Stacks, Reference, or Reserves sections of the MAIN library building. If the book was checked out, the due date would be given instead of a location desk:RESERVES Indicates that the book must be asked for at the reserves/circulation desk, not looked for in reference or stacks areas. circ rule: RESRV_2HR Indicates the SMC Library circulation rule for regular reserves items: they may only be checked out for two hours use in the Library Examine the OPAC record above to analyze, recognize, and define some common components of an OPAC record. Finding a Book on the Shelf As discussed before, books in the SMC Library are classified (i.e. described and arranged by subject and identification number) according to the Library of Congress Classification System (LC). It was started by the Library of Congress in Washington, DC, and is used by many other libraries. (Many libraries, especially public libraries, use the second major classification system, the Dewey Decimal Classification System (DDC), which uses numbers to indicate the subjects.) LC uses the letters of the alphabet to indicate the broad subjects of books. For example, “B” stands for subjects in philosophy and religion. Most science books fall under “Q”. Letters, combined with other subject numbers and author codes, make up the call numbers for books. The call number identifies and describes the book, and indicates where it is shelved. You can search for books by using the OPAC and following the directions onscreen, and on previous pages. 6 When you find a book you want, write down its call number. If it is available and located in the stacks, go to the book area called the Stacks that begin just after the Reference works near the reference desk and continue, in call number order, to the area opposite the circulation desk. Go to the area where the first letter of the call number that you want appears; then follow the call number letter by letter, number by number, etc., until you have found the book with exactly that number on its spine. Consult the summary of instructions for using the Library catalog for a listing of steps to follow when searching for information in the SMC Library OPAC. Periodicals When writing research papers and other course assignments, you may need to find periodical articles as well as (or instead of) books for relevant information. Periodicals contain more recent and up-to-date information than books, although the information may not always be 100% accurate. Periodicals are magazines, journals, and newspapers. They are called “periodicals” because they are published at regular periods—such as every day, every week, or every month—instead of just once, like most books. Some periodicals, especially journals, can be published every three or four months or even just once or twice a year. Magazines are general-interest or special-interest publications meant for the average reader. They are usually glossy and contain articles, stories, poems, illustrations, advertisements, etc. Magazines are sometimes dedicated to one subject only, such as fashion or automobiles. Some examples of magazines are: Time, Newsweek, Good Housekeeping, Vogue, Discover, Omni, and Car and Driver. Journals are periodicals containing articles on specific subjects usually written for (and by) scholars and professionals in fields such as medicine, literature, law, music, etc. The word “journal” may or may not appear in the title of the publication. Articles in journals generally contain the results or description of research or critical analysis. Some examples of journals are: JAMA (Journal of the American Medical Association), College English, and American Journal of Botany. Newspapers usually are published every day or week and contain the news of the day or time period covered; commentary; feature articles; and advertising. Some examples are the Los Angeles Times, the Los Angeles Sentinel, and the New York Times. Periodical Indexes and SMC Library Periodical Resources To use periodicals in library research, you need several reference tools. The first such helper is an index. This specific type of index tells researchers exactly which periodical issues contain articles on chosen subjects. The General Science Index (GSI), a book/print index found in many libraries, is this type of resource. GSI only contains article listings on science topics. Since it only deals with one subject area, it is called a subject index. Other indexes, such as The Reader’s Guide to Periodical Literature, contain citations covering articles on many subjects, not on one subject alone. These types of indexes are called general indexes. Listed under each subject heading in a print index, or in a result list from an electronic one, will be all of the articles entered on the subject searched, which came out during the time period covered by the index. The articles could come from any of the periodicals included by the index publishers. Most of SMC Library’s print indexes are kept near the Reference shelves on the first floor. Each of them usually lets the user know which magazines, newspapers, or journals it includes by placing a list of the periodicals in the front pages of each volume. An important exception, however, is Biological Abstracts, published by BIOSIS, which prints its list of indexed periodicals in a separate book entitled Serial Sources for the BIOSIS Previews Database. Electronic indexes usually print their list in a separate file or hardcopy list; some are accessible to searchers and some are not. Ebscohost does allow users to browse their list of included periodicals. The second reference helper that might be needed to locate periodical articles in SMC Library is the Santa Monica College Library Periodical Holdings List. This list is found in the OPAC, and also in red 3-ring binders near the reference computer workstations and the circulation desk areas. Look up a needed periodical alphabetically by its title and the list will indicate whether the SMC Library subscribes to the periodical. It also specifies which dates of the periodical the Library owns. Additionally, it indicates which issues are stored in the bound or unbound periodicals area behind the circulation desk, and which issues are stored on microfilm or microfiche in cabinets near the reference area. You will need proof of current enrollment, such as your student identification card, to ask for periodicals from the bound or unbound periodicals area, but you can go directly to the microform periodical issues (which must be read on special machines nearby). The Santa Monica College Library Periodical Holdings List The computer catalog, or OPAC, tells us which books the library owns. It also tells us which periodicals and other materials the library owns. To search the OPAC to see if the Library subscribes to a specific periodical, click the Library Catalog on the Library Home Page. Type the title of the periodical” (e.g. Newsweek) in the search box, and click the “Periodical Titles” button below the search box. 7 The Periodical Holdings List is another tool that tells Library users which periodicals the Library subscribes to; it is often handier to use than the computer catalog listings. However, although the information contained in the print List comes from the computer records, the OPAC offers more updated information about the periodicals. Copies of the List, in red 3-ring binders, may be found at the circulation desk, near the computer workstations and tables, and in print-index and reference areas. It is updated at regular intervals. All magazines, newspapers, and journals to which the SMC Library subscribes are listed alphabetically by title in the printed List. The List also tells which dates of the periodicals are owned by the Library, and where the back issues of each periodical are kept: bound periodicals and unbound periodicals (single, loose issues) are kept behind the periodicals/circulation desk; and many periodical back issues are stored on microfilm or microfiche in cabinets in the reference area. Using the Periodical Holdings List If you need to know if the Library subscribes to a certain periodical (Newsweek magazine, for example), you would look in the printed List alphabetically under the title of the periodical (in the “N” section for Newsweek) and it would indicate which dates of this magazine the Library holds, and which issues were bound, unbound, on microfilm or on microfiche. If a periodical title does not appear in the List, then the SMC Library does not subscribe to it. When you locate an article you want, especially after using a print index or abstract, your next step is to check our List to see if the Library has the periodical containing the needed article. If the Library subscribes to the periodical, then you must go to the correct area where it is kept to retrieve it. Click the following connection for more details on steps to finding periodical articles in the SMC Library. Print Index Citations: General Science Index Although electronic databases predominate in contemporary library research, there are times when it is preferable or mandatory to use a print index, especially to find information older than a few years. The following example from The General Science Index provides practice in analyzing a citation from a print index. Components of the citation are explained in the list following the citation. Try to match visually each component part of the analyzed entry with the definitions and components of each part of the entry, which appear below the record Hearing See also Auditory perception Auditory interneurones in the metathoracic ganglion of the grasshopper Chorthippus biguttulus [two-year research project ]. A. Stumpner and B. Ronacher. bibl il J Exp Biol v158 p391-410 Jl ‘91 Subject Heading : Hearing What the article is about. Cross Reference : See also Auditory perception Refers the researcher to a related subject heading within the same index volume, where other related articles can be found. Title of the Article: Auditory interneurones in the metathoracic ganglion of the grasshopper Chorthippus biguttulus The name of the article Informational Note: [two-year research project ] A note of additional information about the article that explains, summarizes, or characterizes the article Author(s) of the Article: A. Stumpner and B. Ronacher Name(s) of the person(s) that wrote the article Informational Note: bibl A note of additional information about the article; in this case the abbreviation “bibl” means that the article contains a bibliography Informational Note: il A note of additional information about the article; in this case the abbreviation “il” means that the article contains illustrations Title of the Periodical (abbreviated): J Exp Biol The name of the journal/periodical in which the article appears; in this case an abbreviation for the Journal of Experimental Biology (Title abbreviations are spelled out in the front section of each volume of General Science Index) Volume Number of the Periodical : v158 The volume number of the periodical. Page Number(s) of the Article: p391-410 The specific page numbers where the specific article will be found. Date of the Periodical: Jl ‘91 The date when the periodical issue was published; in this case an abbreviation for the date July 1991. 8 The Internet The World Wide Web provides a number of useful life- and health-sciences websites that would repay investigation by students of the biological sciences. The information in websites differs from that in proprietary databases in that the databases pre-screen and pre-select their information before distributing it (usually for a fee) according to sets of preexisting standards. The documents on the still-evolving Internet, however, are generally not screened according to preestablished academic or other standards; virtually anyone with an Internet-equipped computer can post documents on any and all subjects. A vast quantity of information on the Web is therefore not up to academic professional, scholarly, or authoritative levels. In academic or scholarly databases, the majority of material included has been somewhat pre-selected for the researcher. The publishers have winnowed out material that they believe do not meet the standards they are striving for, or that do not match the needs of their target audiences. Researchers still have to search for and separate out the materials that fit their needs of the moment. But they can select from a largely pre-screened pool of choices, which means that some of the “work”, in a sense, has already been done for them! The present state of the Web, however, offers no such safety net. Researchers using the Web must do all the work of searching out and evaluating their search results for appropriateness and authenticity, often in what seems like a vacuum. Great care should be taken in relying on information from any research source, and even more care should be taken with information from the Internet. This certainly applies to researchers in the sciences, where accuracy and authoritativeness are so important. When using the Internet, choose documents from reliable and stable sources. Use the hints from Cornell and UCLA web pages on evaluating web sites to help you decide. Science Databases (free registration required for some databases) http://guides.library.ucla.edu/start/articles PubMed http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?tool=cdl&otool=cdlotool Access to citations from MEDLINE, PreMEDLINE, other journals in the field of medicine and life sciences, and links to NCBI's integrated molecular biology databases including nucleotide sequences, protein sequences, 3-D protein structure data, population study data sets, and assemblies of complete genomes in an integrated system. consumer health, Entrez, MEDLINE, AIDSLINE, HealthSTAR, HISTLINE, nucleotides, genomes BIOSIS Previews (free registration required for some databases) http://isiknowledge.com/biosis Contains citations and abstracts for journal articles, books, conference proceedings, and technical reports in all areas of biology, related fields such as biomedicine and ecology, and interdisciplinary areas such as biochemistry and biotechnology. Environmental Sciences and Pollution Management http://uclibs.org/PID/77296 This multidisciplinary database provides comprehensive coverage of the environmental sciences. Abstracts and citations are drawn from over 6000 serials including scientific journals, conference proceedings, reports, monographs, books and government publications. PsycINFO http://www.csa.com/htbin/dbrng.cgi?username=ago21&access=ago2121&db=psycinfo-set-c&adv=1 Abstracts and citations to the scholarly literature in the psychological, social, behavioral, and health sciences. Many link to full-text. 99% are peer-reviewed journals. Web of Science http://isiknowledge.com/wos Web of Science is comprised of Arts & Humanities Citation Index, Social Sciences Citation Index, and Science Citation Index. Covers thousands of journals in a wide array of disciplines. The preceding sections of the tutorial have dealt in large degree with the organization of library materials and approaches to accessing them. This section is concerned with specifics of some principal resources you will need to use to fulfill the Biology 21 library assignments. The following information introduces MEDLINE, a much-respected database of the National Library of Medicine. Practice searching for your subject in MEDLINE to gain experience in researching a scholarly website. The United States National Library of Medicine 9 The National Library of Medicine (NLM) is “the world’s largest medical library”, a U. S. government agency headquartered in Maryland. The NLM has made many of its databases available to the public through the Internet. Two of the main avenues to their information is through PubMed or the NLM Gateway, both of which provide access to MEDLINE. PubMed and MEDLINE The web-based NLM Gateway allows simultaneous searching of several of NLM’s databases at once, including MEDLINE, OLDMEDLINE (containing journal references published before 1966), MEDLINEplus (consumer health topics) and others. The Internet, which can be used to search such websites as MEDLINE for citations and abstracts (no direct full text) of relevant journal articles, is accessible from all SMC Library workstations in the reference area. Current SMC students and staff do not always have to be physically present on the SMC Library premises to gain access to databases and other electronic resources. The Library’s online offerings are available from all Internet-equipped labs on campus. In addition, current SMC staff and students may access them from home, or from any off-campus Internetequipped computer to which they have access. You must establish a user account with the College, obtaining a username, password, and e-mail privileges. Sign up here. MEDLINE is an online database that is often of great help to health and life science researchers. It began years ago as the “Medical Literature, Analysis, and Retrieval System” (or MEDLARS) and has now become MEDLINE (Medical Literature, Analysis, and Retrieval System Online). It is probably the most well-known of the NLM’s databases, and is considered by them to be their “premier bibliographic database. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi PubMed, an online searching service of the National Library of Medicine, provides access to over 11 million MEDLINE citations back to 1966, and additional life science journals. PubMed includes links to many sites providing full text articles and other related resources. This resource is one that life sciences students should become familiar with for its vastness, impressiveness, and the fact that it is free to anyone with Internet access. It is part of a retrieval mechanism called Entrez. PubMed is a database of bibliographic information drawn primarily from the life sciences literature, with a focus on biomedicine. PubMed contains links to full-text articles at participating publishers’ Web sites as well as links to other third party sites such as libraries. Click the following to go to the PubMed site to practice searching in MEDLINE via PubMed’s interface. Or you may want to study the PubMed tutorial to become more familiar with its contents and capabilities before beginning trial searches. Try to search “Human Genome Project” Articles on the Human Genome Project can be found at the SMC Library in Ebscohost MasterFile Premier and General Science Full text. Biological Abstracts Biological Abstracts (BA) is one of the most useful researching tools for students of biology. As its title suggests, it is not just an index but also an abstract: a research tool that supplies not only a basic citation for each article but also a summary (or abstract) of each article as well. Much of the material found in this resource on life-sciences subjects comes from scholarly journals. All abstracts are numbered and then grouped in broad subject or classification areas. In the print versions owned by SMC Library, access to abstract contents is provided mainly by a keyword index for each volume. In citations of journal articles, some journal titles are abbreviated. The explanations of the abbreviations are not found in the abstract volumes themselves, but in a book in the SMC Library collection called Serial Sources for the BIOSIS Previews Database. At UCLA’s Biomedical (or “Biomed”) Library, Biological Abstracts can be found archived in print form, and shelved primarily in the Library’s journal stacks. BIOSIS, Inc., the publisher of Biological Abstracts, describes it as “your key to the world’s life sciences journals. Comprehensive coverage and context-sensitive indexing make the information in BA essential for all life sciences researchers. BA directs users to information on life science topics from botany to microbiology to pharmacology, serving to connect researchers with critical journal coverage. “Whether you study botany, pharmacology, biochemistry, or evolutionary ecology, BA has the journal articles that your research depends on. “BA indexes articles from over 4,000 serials each year. This publication also offers over 360,000 new citations each year. Nearly 90% of citations include an abstract by the author. Almost 5.8 million archival records are available back to 1980. BA articles originate from journals all around the world, and cover topics in every life sciences discipline. If the information you need lies in the life sciences, BA should be part of your information solution.” For current research, the print version has largely given place to CD or online counterparts of Biological Abstracts, including a version called BIOSIS Previews. SMC Library does not at present subscribe to BIOSIS Previews or to 10 Biological Abstracts. But the Library does maintain some older print copies to acquaint students with the basics of using Biological Abstracts, because of its importance as a life sciences resource. Analysis of a Record from Biological Abstracts An abstract from the print version of Biological Abstracts is reproduced below. Its component parts are explained in the list below the abstract. When you analyze the citation, you’ll find that it contains the same kind of information found in other indexes or abstracts that you have already examined in this tutorial, as well as additional information not found in previously examined resources. For further information on using Biological Abstracts, click here. Visually match the identifications and explanations found below the abstract with the actual components of the abstract; this will help you gain a fundamental understanding of the structure and the information found in such a record, as well as helping you to prepare for the quiz below. 118640. NAUMOV, G. I.* and T. I. FILIMONOVA. (All-Union Res. Inst. Genet. Sel. Ind. Microorg., Moscow.) MIKOL FITOPATOL 23(1): 34-37. 1989. [In Russ.] Absence of killer strains in Moscow commercial populations of Saccharmomyces yeast. – Commercial yeast populations from 4 Moscow breweries were studied, as was a collection of 123 beer strains. Data were presented on the sensitivity of the commercial populations to the K2 toxin. It was shown that the commercial and museum beer strain populations do not contain killer strains, but this sensitivity of the strains to the K2 toxin can lead to the contamination of their populations with wild killer strains. Recommendations were made for creating beer strains resistant to yeast toxins. Abstract/reference number: 118640 Author(s) of the article: NAUMOV, G. I.* (the asterisk [*] means that this is the author whose address is given below), and T. I. FILIMONOVA. Author’s Address: All-Union Res. Inst. Genet. Sel. Ind. Microorg., Moscow.) Title of Journal (abbreviated): MIKOL FITOPATOL [Mikologiya i Fitopatologiya] Volume Number of the Journal: 23 Issue Number of the Journal: 1 Page Numbers of the article: 34-37 Date of the Journal: 1989 Explanatory Note: “In Russ.” [the article is written in Russian] Title of the Article: Absence of killer strains in Moscow commercial populations of Saccharmomyces yeast. Abstract/Summary of the Article: Commercial yeast populations from 4 Moscow breweries were studied, as was a collection of 123 beer strains…. [etc.] Online Searching: Library Databases Ebscohost MasterFile Premier and General Science Full-text 1984-Present The fundamentals of Boolean searching, the basics of using the OPAC, and an introduction to using print indexes and the Periodicals Holdings List have been explored in previous pages. And several of the searching principles learned in prior readings can be applied to searching Ebscohost MasterFile Premier. When you are at SMC you have on-campus access to Ebscohost without having to log in with your SMC username and password. However, for off-campus access to Ebscohost, and to other Library online resources, you will need to use the username and password provided by your SMC student account. Ebscohost is one of SMC Library’s electronic periodical indexes, used in order to find appropriate articles from magazines, newspapers, or journals. Ebscohost is a web-based database to which the SMC Library subscribes. This online general index comes to us via the World Wide Web, but it is a proprietary database published by the Ebsco company. Since Ebscohost is a general index, it contains articles on many subject areas instead of just one. In addition, it offers keyword, customizable searching and the full text of many of its articles, which come from magazines, journals, newspapers, and other source General Science Full-Text 1984-Present Ebscohost is just one of the online databases available at SMC Library that would be of interest to life sciences students. Others include CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature). It is an index to health sciences journals and provides citations for the indexed articles, but not the entire text of the articles. See a complete list of SMC’s Library Databases. General Science Full-Text is another useful online periodicals index/database. Again, while you are at SMC you have oncampus access to General Science Full-Text without having to log in with your username and password. Just as with Ebscohost, however, you need to use the username and password provided by your SMC student account, for off-campus access to General Science Full-Text. 11 General Science Full-Text is a database that includes articles and citations from science-related magazines and journals, starting from 1984. By far the greater portion of its entries are abstracts or citations of journal articles, with its available full-text articles appearing from 1995 onward. This online periodicals index does not as yet index nearly as many periodicals as Ebscohost, but its concentration on one subject area, the sciences, makes it a valuable resource nonetheless. The instructions below offer basic steps to searching this database. For more information, see this page on How to search General Science Full-Text. In SMC’s Library Databases, find and click General Science Full-Text 1984-present. At upper right, click “SearchPlus”. At the search screen, type your subject /keyword in “Enter terms, select options” box. Choose where the keyword should appear, e. g. words anywhere, subject etc. Click the AND option to add a second term to your search, if applicable. Analyzing a Record from General Science Full-Text The record below represents an entry from General Science Full-Text. Its components are explained in the list following the record. Note that it carries substantially the same type of information found in Ebscohost records, with a different layout and different details. This reinforces the fact that different indexes usually display the same core information, with individualizing details, additions, or omissions. Compare visually the differences and similarities of both indexes as exemplified in both sample records, noting the styles and information offered. Use the information in the analysis below to help you decide on the answers to Quiz 4B, which follows this section: Full Text: When the entire article is available in General Science Full-text’s database, this option appears. Choose to view the article as an HTML document or as a PDF file (using Adobe Acrobat) Title: “The risks for late adolescence of early adolescent marijuana use” Personal Author: The person(s) listed as writing, or being responsible for, the content of the article, as opposed to an organization (i. e., “Corporate Author”) listed as writing or being responsible for the content of the article: Brook, Judith S.; Balka, Elinor B.; and Whiteman, Martin Peer Reviewed Article: Indicates whether an article is from a scholarly research-level source. Y = Yes; N = No Abstract: The summary of the article Publication Year: 1999 Journal Name: Title of the Periodical in which the article appeared Source: Title of the Periodical, or other supplier, that provided the article Physical Description: Informational note giving useful additional data about the article: bibl: the article contains a bibliography il: the article is illustrated Language of Document: The original language in which the article is written: English Descriptors: Subject headings/keyword terms or phrases that describe the topics treated by the article: Youth—Conduct of Life; Marijuana; Drug Abuse Document Type: Indicates whether the article is a “Feature Article”, UCLA’s Biomedical Library UCLA’s Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library is a major health sciences research library. Visitors can be overwhelmed by the multi-level layout and floor plan of the place, but the locations of books and journal volumes are easily learned and make investigations there more easily navigable. The Biomedical Library uses the National Library of Medicine Classification System extensively to classify their materials. For more details, the Biomedical Library Home Page has extensive information about the library’s materials, organization, services, and policies. The Biomedical Library subscribes to many research journals as well as, of course, to other publications and materials. The library keeps print back issues of most volumes of Biological Abstracts in reference and stack areas, but most basic research is done online. Currently, one of the main databases used by UCLA Biomedical library researchers is BIOSIS Previews, an online product by the same publishers that produce the print version of Biological Abstracts. Available online information from Biomedical Library computer workstations can be printed or downloaded to disk, just as similar information can be retrieved at SMC Library. Click here for instructions on searching BIOSIS Previews, helpful for guidance in becoming familiar with this resource and for printing, e-mailing, and downloading search results. HELPFUL HINT: Print out a copy of the guides to take with you to UCLA. Locating Materials in the Biomedical Library 12 Before traveling to UCLA to complete your library assignments, review the information below for help in negotiating the Biomedical Library’s resources. The Biomedical Library Call Number Locations chart can help you locate call number areas for needed books and journals. HELPFUL HINT: Print out a copy of the locations to take with you to UCLA. Here is some more information: directions to UCLA, public transportation and some Biomedical Library links. What does the Biomedical Library have? The Biomedical Library has over 550,000 volumes, 5,400 current journals, and a number of instructional media resources (e.g., audiovisual material and computer-based instructional systems). The Library’s collections include comprehensive coverage of the health and life sciences and psychology. How do you find material in the Library? For items owned by any UC system libraries, use MELVYL, the UC Library online information System, which contains information about most books, audiovisuals, and computer programs, and all currently received journal titles. How can you get access to services or materials? UCLA faculty, staff, and students can use all services and materials which the Library provides. A current UCLA ID and/or library card can be used to obtain services and materials. Eligibility for non-UCLA individuals for services and materials will vary depending on the type of library card issued. Melvyl: The Melvyl Catalog provides information about articles, books, journals, and other materials held by UCLA, other University of California (UC) campuses, and libraries worldwide. Many records contain links to full-text articles from selected databases. Additional materials in all formats, including full-text articles from journals and books not indexed in Melvyl, may be accessible from the Databases by Subject section. Use Melvyl when you want an encompassing, general search for books, articles, and more from all the UCs or to request book delivery from other UC campuses using the "Request" button if UCLA does not own a particular title. Searching for primary literature Primary and Secondary Articles Primary and secondary sources form the basis of research. Primary vs. secondary sources. Primary literature are sources that report original work, written by the researcher(s) who did the work, peer reviewed, and published in a journal. They can be diaries, letters, paintings, patents, photographs, poems, or, in the case of scientific research, a research report. Secondary sources are. Secondary sources are accounts written after the fact, are often reviews, commentaries, or summaries. They are interpretations and evaluations of the primary sources. The data (figures) will have a reference or citation indicating where it came from. Often there are no figures or tables, i.e. no data. Gray literature are sources that do not have normal publisher. They are often called “reports” or “technical reports” and are not published on a regular basis. Many are produced by and for government agencies or scientific advisory or study groups. Although the work may be as rigorous as a journal article, the peer review process is inconsistent. Compare the two with respect to organization, format, style of presentation, depth, breadth, and intended audience (readers). Type of work Source Organization and Format Depth and Breadth Content Intended audience (reader) Example Primary Original, creative work First-hand information More structured (Intro, Method, Results, etc.) More in depth Factual Focused group Lab report, journal article 13 Secondary Interpreted or analyzed work One or more steps away from the original event Review Broad understanding Interpretive General audience Book, encyclopedia, editorial Remember that a good careful search will make writing the paper easier when you have lots of references that are relevant to your project. Writing the paper with several peripherally related articles will be a struggle. Good searches should be comprehensive and well-focused. It will generate most of the relevant articles and minimize the irrelevant articles. Good search terms are important in successful searches. If you already have a reference, keywords are often gleaned from the title of the paper. Most journals require Keywords be listed after the abstract. Remember that scientific terminology is very precise. Searching is trial and error. If you start with a specific term (e.g. genus species, Drosophila melanogaster) and get no “hits,” broaden your search to just “Drosophila.” If that does not work, go to the family Drosophilidae or the order Diptera. At the same time, don’t try “Insect.” You may get several million hits. The same principal applies in reverse if your keyword is too broad. If you type Canis and get 100,000 hits, narrow the search to Canis lupus. The terms AND and OR are valuable tools in running searches. Linking terms with OR generates more comprehensive (broader) searches. Remember that multiple terms or phrases may be used to describe the same concept. The excretory system is also the kidney. Nephridial and renal are synonomous terms. Linking terms with AND generates well-focused (narrower) searches. “Cardiac” AND “exercise” will generate a more focused search than each term alone. “Female” AND “senior” AND “Asian” AND “cardiac” AND “exercise” is even more focused, but probably overkill. If you are getting too many hits or you want a more focused search, most databases have tools to limit searches by publication, species, language, online availability, date and other criteria. Most search engines scan the entire text for keywords. You can sometimes limit the search for terms in the title and/or abstract. Exploit what is free. Going up and down the 13 floors of the UCLA Biomed Library is a drag, especially if the volume is not available. Then, if the article comes from an older volume, it is housed and archived offsite. It may take a few days for the library to process your request to see the journal. Since most of you will not have an UCLA library card, you cannot do this. You will need to get a friend already enrolled at UCLA to request the article for you. Fortunately, articles in an ever increasing number of journals are published for free online in PDF or in full-text format. Even if articles are not available in PDF on the journal website, the authors often purchase the article in PDF and make the paper available to interested parties for free. Since most papers now give the author’s email address, go to the author’s homepage or website. Most scientists now post their most recent, or most salient, or most important papers. Many are available in PDF. Full-text format often does not print well, but its advantage is that you can move from section to section by links. The reference lists are often linked to online versions of cited references. Sometimes there is also a list of papers that have cited this paper. In addition, some journals are completely online, and there are no hard copies. Once you have found what looks like a “good” article, most search engines now have a direct link to the online article. You need to learn to quickly read/skim/scan the article to see if it fits your needs. Scan the title, note the authors, and read the abstract. The end of the introduction often has the hypothesis or purpose. Take a quick look at the figures and tables. Jump to the back to see what the summary and conclusions are. Once you have found one key article, the door seems to open like Pandora’s Box. Often, if the author wrote one article on the subject, he/she wrote others on the same subject. Search for articles by that author. As noted above, go to the author’s website/homepage to see if other articles are posted. Next go through the literature cited. The author has done a literature search on the subject as well! Scan through it for relevant papers. Consider which online search engine you use. At UCLA, the main database is PubMed, www.pubmed.gov. Note that this is primarily a medical search engine, because there is the medical center. You won’t find much on animals and plants. You need to go to Biosis. Similarly there are specific online databases for psychology, geology, etc. Other Search Engines - Google.com is primarily for lay subjects, but there is a more scientific related search. On top right above the window, click on “more.” Click on “even more.” Scroll down to “Scholar.” Now when you click on “Advanced Scholar Search,” you can set the parameters for your search. This will often take you to the online source and most times, you can at least see the abstract, if not the full article. The beauty of this is that you can do this at home. Biosis needs to be accessed at UCLA. That said, I thought that Biosis could be accessed at our SMC library, which is linked to UCLA. Check it out. Remember that search engines are based on who pays to be put on top of the list and how many hits the site gets. So every time you search, the rankings may change, so it is good to try again at a later time. Simple things like reversing your keywords makes a difference. Review the section above and prior sections, if applicable. 14 Citing Your Sources http://guides.library.ucla.edu/start/citing Citation Style Guides - Online When citing sources be sure to use the proper citation style for the course. Below are links to ONLINE summarized citation rules from some of the more popular style guides: APA Citation Quick Guide http://www.cdlib.org/services/info_services/docs/UC_APA_CitationGuide_021810.pdf Via University of California Libraries. APA Style FAQ from American Psychological Association http://www.apastyle.org/learn/faqs/index.aspx APA (American Psychological Association) http://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/560/01/ Via OWL at Purdue. MLA (Modern Language Association) http://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/747/01/ Via OWL at Purdue. Chicago Manual of Style http://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org/16/contents.html The 16th edition of the Chicago Manual of Style is fully searchable online. Chicago Manual of Style-Quick Guide http://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org/tools_citationguide.html Via University of Chicago Press. Turabian http://www.press.uchicago.edu/books/turabian/turabian_citationguide.html Based on the Chicago Manual of Style. Research and Documentation Online http://bcs.bedfordstmartins.com/resdoc5e/ The information on this site is also available in a print book, Research and Documentation in the Electronic Age, Fifth Edition, by Diana Hacker and Barbara Fister. Annotated Bibliographies Preparing an annotated bibliography is often the first step in writing a research paper. Sometimes it is a stand-alone assignment. Annotations usually include both description and some evaluative comment. See Purdue University's OWL (Online Writing Lab) page (linked below) for more help in preparing an annotated bibliography. Annotated Bibliographies--Definition and Format http://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/614/01/ This page from the OWL at Purdue provides basic information with links to other parts of the OWL website. Citation Style Guides - Print For a general introduction to academic citation and intellectual property, see Bruin Success with Less Stress. For more detail, consult the complete printed style manuals, available in many campus libraries: Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (6th edition) http://catalog.library.ucla.edu/vwebv/holdingsInfo?bibId=6299880 MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers (7th edition) http://catalog.library.ucla.edu/vwebv/holdingsInfo?bibId=6278113 Chicago Manual of Style (16th edition) http://catalog.library.ucla.edu/vwebv/holdingsInfo?bibId=6523875 Turabian's A Manual for Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and Dissertations (7th edition) http://catalog.library.ucla.edu/vwebv/holdingsInfo?bibId=5702186 Congratulations, you have finished the tutorial! 15