On college and career readiness: What do we know and what will

What Does College and Career Readiness Mean? How Will We Know?

Prepared Remarks for a Common Core Forum in Kirkland, Washington

Sandra Stotsky

June 27, 2015

I. College readiness was never defined by the Common Core project . Nor did state boards of education inquire in 2010, or whenever they adopted Common Core’s College and Career Readiness Standards. While higher education math faculty have a better idea than English faculty what students need to know for, say, freshman calculus courses,

English or Humanities faculty in higher education have so far been unwilling to say what books as examples one should be able to read in order to be judged college-ready. Yet, college-level reading is needed for all college-level study. In my remarks today, I focus on my own area of expertise—ELA.

II. Most American high school graduates today cannot read college-level textbooks.

We know that the average American student today is not ready for college from two independent sources: (1) Renaissance Learning’s latest report (2015) on the average reading level of what students in grades 9-12 choose or are assigned to read, and (2) the average reading level of the books colleges assign incoming freshmen to read (the 2013-

2014 “Beach Book” report). From these two sources, we learn that average American high school students read at about the grade 6 to 7 level. This is hardly the reading level needed for college textbooks and other readings assigned in college.

Although Common Core promised to make all students college-ready, it didn’t tell the state boards of education who bought into this idea (or the public at large) what reading level that phrase meant. Nor did any state board member ask so far as we know. There is no information available from Common Core’s own documents or from the developers of

Common Core-based tests what college readiness in reading means. What can a high school student judged to be college-ready actually be able to read? Who knows?

Most media outlets in this country rarely discuss these reading issues at all. They don’t find out the reading level of what students in our elementary, middle, and high school classes are being asked to read and then ask how those reading levels can make students ready for college-level reading by grade 11. They rarely tell us the titles and authors of what they are reading so we can try to figure out ourselves if a curriculum addressing

Common Core’s standards is really going to raise students’ reading levels.

III. Flaws in CC’s ELA standards

A. Most are content-free skills, not “content” standards .

Example 1. “Cite strong and thorough textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text, including determining where the text leaves matters uncertain.”

Example 2. “Determine two or more themes or central ideas of a text and analyze their development over the course of the text, including how they interact and build on one another to produce a complex account; provide an objective summary of the text.”

1

Examples of authentic ELA literature standards

*In California’s pre-Common Core standards for 11/12:

3.7 Analyze recognized works of world literature from a variety of authors: a. Contrast the major literary forms, techniques, and characteristics of the major literary periods (e.g., Homeric Greece, medieval, romantic, neoclassic, modern). b. Relate literary works and authors to the major themes and issues of their eras.

*In Massaschusetts’ pre-Common Core standards for grades 9/10:

16.11: Analyze the characters, structure, and themes of classical Greek drama and epic poetry.

B. Common Core’s standards expect English teachers to spend at least half of their reading instructional time at every grade level on informational texts . They contain 10 reading standards for informational texts and 9 for literary texts at every grade level, reducing literary study in the English class to about 50%. No research studies support increasing the study of nonfiction in English classes to improve college readiness.

C. Common Core’s standards reduce opportunities for students to develop analytical thinking . Analytical thinking is developed when teachers teach students how to read between the lines of complex works. Thus, reducing complex literary study in the English class in order to increase informational reading, in effect, retards college readiness.

D. Common Core’s standards discourage “critical” thinking.

Critical thinking is based on independent thinking. Independent thinking comes from a range of observations, experiences, and undirected reading. No standards for writing a research paper like those spelled out in the pre-Common Core Massachusetts ELA standards.

IV. Why a Forthcoming Fordham Institute Study Cannot Tell Us Much

The Thomas B. Fordham Institute and the Human Resources Research Organization are now conducting a study of how well aligned several national assessments are to the

Common Core State Standards and the extent to which they meet the criteria for highquality assessments established by the Council of Chief State School Officers. However, we are not told why CCSSO is qualified to establish criteria for high-quality assessments.

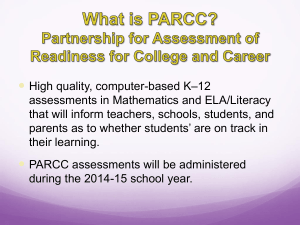

Nor can the test items for the 2015 PARCC or SBAC tests be discussed in a public report.

The public CAN examine “sample” and “practice” test items that PARCC and SBAC have made available online. And parents and teachers CAN testify on what students say about the test items they have responded to on their computers or in their test booklets.

But researchers cannot present an evaluation of the grade appropriateness of their test items or a comparison of the contents of their test items because they are not allowed to say anything about the actual contents of the test items if indeed they examined them.

Nor are K-12 teachers being asked to take the tests they give their students and offer their professional judgments.

2

Until all the test items used in Common Core-based tests in 2015 at every grade level are available to all citizens for inspection under secure conditions, we must consider their results invalid. Moreover, there are significant issues in Common Core-based tests that need public attention until the millennium arrives.

V. What I found out by looking at Practice test items released by PARCC.

* The overall reading level of PARCC sample test items in most grades seems to be lower than the overall reading level of test items in ELA tests (MCAS) based on the pre-

Common Core standards in Massachusetts—sometimes by more than one reading grade level. E.g., an excerpt from The Red Badge of Courage is an example in the 2015 grades

10 and 11 PARCC. But an excerpt from this novel was assessed in a pre-2010 grade 8

MCAS. E.g., an excerpt from Joseph Conrad’s

Heart of Darkness is an example in the

2015 grade 11 PARCC but appears in a 2010 grade 10 MCAS. Our state tests were aimed to high school diploma readiness, not college readiness.

* PARCC doesn’t tell us who determines the cut (pass/fail) score, where it will be, and who changes it, and when. Cut scores on pre-Common Core state tests were set by the state’s own citizens.

* PARCC test specifications do not indicate from what authors or kinds of text the literary passages are to be drawn, and how the four literary genres are to be balanced.

* PARCC 2015 grade 11 test samples are not aligned with Common Core’s standards; there are no passages from founding political documents.

* PARCC offers too many tests at each grade and across grades.

* PARCC requires extensive keyboarding skills and too much time for test preparation.

* PARCC plans to provide only a few released test items for teachers to use, it seems.

* The PARCC tests are very long even though they have been recently shortened.

* The writing prompts in PARCC 2015 do not elicit “deeper thinking” because students are not given a provocative question about a reading assignment and encouraged to make and justify their own interpretation of an author’s ideas based on a range of sources, some self-chosen. They are almost always given the sources to use, beginning in grade 3,

The two-part multiple-choice format in PARCC and SBAC often requires students to engage in a textual scavenger hunt for the specific words, phrases, or sentences that led to their own thinking when answering the previous question. This two-part multiple-choice format is especially taxing and problematic in the early grades. E.g., in grade 3: “Part B:

Which sentence from the story supports the answer to Part A?” “Which detail supports the answer to Part A?” These two-part questions are poorly worded, confusing, tedious, unfriendly to children, and cumbersome.

3

VI. Recommendations :

1. Fewer grades tested (just 4, 8, and 10), as in the 1994 authorization of ESEA

2. Paper and pencil tests; no computer-based tests

3. All or most test items released every year

4. Tests requiring less time for preparing for and taking the tests

5. Test passages and questions chosen and/or reviewed by the state’s English and math teachers

6. A state-determined cut score

4