National Health Committee - Recommendation

advertisement

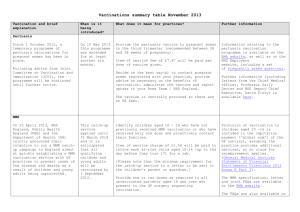

Committee Report number: 2012022 Paper for Meeting on: 24 April 2012 NHC reference: Action Point from NHC meeting on 26 March 2012 The National Health Committee Recommendation - Rotavirus Vaccination Executive summary i. At the previous Committee meeting (26 March 2012) a draft of the Rotavirus assessment report was provided to the Committee as part of the ‘stage gate’ process of determining what further evidence the Committee requires prior to making a decision. ii. The Committee instructed the Executive to further investigate the impact of targeting vaccination to patients at high risk of nosocomial rotavirus gastroenteritis on the clinical- and cost-effectiveness of the programme. A limited ‘light’ literature search was suggested and the findings of this search are presented in Appendix 1. iii. This recommendations paper summarises the key points from the draft rotavirus assessment report presented at the last Committee meeting (see paper # 2012014) and the additional evidence retrieved (refer para 2); detailing why the intervention was chosen for assessment, the methods used in the assessment, and a brief discussion of the results and limitations. iv. The paper uses this evidence to evaluate the performance of the intervention against the Committee’s 11 decision-making criteria, and makes a recommendation consistent with this. v. Finally, the circumstances under which a review of the recommendation would be triggered in the future are described. It is recommended that you: a) Agree that the Committee has sufficient information to make a decision. Yes / No b) Agree to recommend to the Minister of Health that the Ministry of Health should not fund the universal vaccination of children for rotavirus gastroenteritis. Yes / No b) Consider that if an alternative recommendation is preferred, further work by the Executive is required to determine the most acceptable and clinically- and cost Yes / No –effective method of implementation (as per assessment report tabled at 26 March meeting, refers to paper #2012014). Committee Report number: 2012022 Preamble 1. Relative to other OECD countries, New Zealand has unusually high rates of infectious diseases such as campylobacteriosis, acute rheumatic fever, childhood pneumonia, meningococcal disease, and skin infections1. 2. A recent New Zealand study has also shown that infectious diseases make the largest contribution to acute hospital admissions and that over the last 20 years rates have increased more than for any other major cause2. The age-standardised rate of acute admissions for infectious disease has also risen much more than the rate for non-infectious disease admissions and the risk of admission is significantly higher in the most economically deprived populations, in Maori and Pacific peoples, and in the youngest (under 5 years) and oldest age groups (over 70 years). 3. The study found that infectious disease categories with the most acute hospital admissions were lower respiratory tract infections, skin and soft-tissue infections, and enteric infections (associated with the intestine). Bacterial, rather than viral are the main drivers of infections. 4. These findings support the experience and current strategies of many District Health Boards; many of which are currently prioritising child health and in particular the prevention and treatment of these infectious diseases. Policy Question 5. The purpose of this paper is to recommend whether, on the basis of the NHC’s assessment of the evidence, and awareness of competing priorities in infectious disease control and child health, the Ministry of Health should fund the universal vaccination of infants against rotavirus gastroenteritis. 6. It follows a recommendation by the Immunisation Technical Forum (ITF) that a two dose rotavirus vaccine be added to the immunisation schedule. No preference for either the Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD) or GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) vaccines was expressed by the ITF. Rationale for assessment 7. The estimated annual incidence of rotavirus is 1,500 per 100,000 of the population, the incidence of hospitalisation for rotavirus is 22.5 per 100,000 of the population, and the annual rotavirus mortality rate is approximately 0.01 per 100,000. 8. Rotavirus vaccination is recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO). The United States, Australia, and parts of Europe (including Austria, Belgium & Finland)(World Health Organization, 2011), have all adopted recommendations to routinely immunize children for rotavirus. However in England it is currently felt that the public health risks posed by rotavirus do not warrant routine vaccination3 and in Canada decisions around public funding are awaiting the results of cost-effectiveness analyses4. 9. In New Zealand, rotavirus vaccination is recommended, but not currently funded for all infants (the first dose must be received by age 15 weeks) and especially infants who will be regularly attending early childhood services or where there is an immune-compromised individual living in the household. 1 Baker, M. G., Barnard, L. T., Kvalsvig, A., Verrall, A., Zhang, J., Keall, M., et al. (2012). Increasing incidence of serious infectious diseases and inequalities in New Zealand: a national epidemiological study. The Lancet(DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61780-7). 2 Baker, M. G., Barnard, L. T., Kvalsvig, A., Verrall, A., Zhang, J., Keall, M., et al. (2012). Increasing incidence of serious infectious diseases and inequalities in New Zealand: a national epidemiological study. The Lancet(DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61780-7). 3 http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Rotavirus-gastroenteritis/Pages/Prevention.aspx 4 http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/ccdr-rmtc/10vol36/acs-4/index-eng.php National Health Committee April 2012 Page 2 of 16 Committee Report number: 2012022 10. In 2009, the Immunisation Technical Forum (ITF) recommended that a two dose rotavirus vaccination programme be publicly funded for infants. 11. The ITF, appointed by the Director-General of Health, reviews the Schedule every three years and makes recommendations on the use of current vaccines and new vaccines (or new combinations of vaccines) to be added to the Schedule. 12. The ITF bases its advice on technical evidence on the clinical effectiveness of new vaccines, epidemiology, availability of new types of vaccines and sector capability. Historically, a full HTA of a vaccine has not been undertaken, and the other domains (such as value for money, societal & ethical, and feasibility of adoption in the system) have only been considered on an ad-hoc basis. 13. A full assessment of the addition of rotavirus to the vaccine schedule was needed to support advice to the Minister on a budget bid in September 2012 on whether or not to add the rotavirus vaccine to the Schedule at its next revision in 2014. 14. The rationale for the involvement of the NHC stems from the: Immunisation team needing to show it is taking account of value for money in vaccines prioritisation NHC wanting to signal their intent to work in the area of vaccines in the future Technology Status & commercial considerations in New Zealand 15. Both Rotarix® (manufactured by GlaxoSmithKlein) and RotaTeq® (manufactured by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp) vaccines are currently available in New Zealand (Table 1). The Rotarix vaccine is given in two oral doses at the same time as the routine Schedule, while the RotaTeq vaccine is administered as a three-dose oral course at the same time as the routine Schedule. 16. No preference for either the Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD) or GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) vaccines was expressed by the ITF. Table 1: Brands of Rotavirus vaccine approved for distribution in New Zealand Brand Registration situation Advertised unit price ($NZ) Rotarix Oral Vaccine Oral Consent given, and approved: $107 to $180 ($80 suspension, 1000000CCID50 26/03/2009 wholesale) (Prescription) Rotarix Powder with diluent for oral Not marketed, but Currently unavailable for suspension, 1000000CCID50 approved:11/04/2008 private purchase (Prescription) RotaTeq Oral suspension, 2mL Consent given, and approved: Currently unavailable for (Prescription) 22/03/2007 private purchase Source: Medsafe (http://www.medsafe.govt.nz/regulatory/ <date accessed: 28/02/12>) 17. The required annual volume of vaccine for a three dose schedule, assuming 100% uptake would be approximately 180,000 units (an entire birth cohort). However, uptake is likely to start lower and increase over time from around 30% (54,000 units) to hopefully reaching about 85% (153,000 units) after five years. A two dose schedule would require slightly less than the volumes detailed above; with 30% uptake requiring 36,000 and 85% requiring 102,000 doses). 18. Overall the introduction of the rotavirus vaccine to the schedule would mean a long term commitment to publically funded provision of the vaccine. This commitment has important commercial implications as it indicates to suppliers that they will have an on-going captive National Health Committee April 2012 Page 3 of 16 Committee Report number: 2012022 market for their vaccine. Furthermore, unlike the varicella vaccine where different brands of the vaccine can be used for different doses in the same individual, the available rotavirus vaccines are not interchangeable, making it more difficult to switch between competing suppliers. 19. While most patents expire after 20 years, enabling the entry of generics into the market after this time, vaccine manufacturers are able to develop their vaccines in a way that enables slight changes in the formulation to be re-patented; extending the time the company has a monopoly in the market by preventing the entry of competitors. 20. These issues mean that negotiating good prices for vaccines is incredibly difficult, particularly after a decision has already been made to add the vaccine to the schedule. Methods 21. Health Technology Assessment is a multidisciplinary field of policy analysis that studies the medical, economic, social and ethical implications of development, diffusion and use of health technology. It usually involves systematic reviews of the literature, epidemiological and financial analysis of administrative health data, economic evaluation and budget impact analysis, and public and health sector engagement. It aims to answer a specific set of research questions across domains in order to answer an overall policy question around investment. The method used in the assessment of the addition of rotavirus vaccine to the immunisation schedule is described below. 22. On the 26 September 2011 the Ministry of Health reference librarians systematically searched the sites of key Health Technology Assessment (HTA) agencies and repositories using the following search terms: Rotavirus. Following this initial search of HTA agencies and repositories, Ovid MEDLINE® and Cochrane Library were searched for scientific journal papers published between 1 January 2009 and 28 October 2011. The search terms used were: cost-effectiveness, cost-benefit, cost-utility, economic evaluation, economic model, decision analysis, rotavirus vaccination. Results were limited to either systematic reviews OR studies based in the United States, Europe, Canada, Australia, or New Zealand. No language limits were applied. A subsequent search of EMBASE for papers published between 1 January 2009 and 11 November 2011, using the same inclusion and exclusion criteria was also undertaken. The reference lists of identified publications were not searched. 23. Abstracts were sifted through and categorised, on the basis of their content, into one of four domains: Economic, Clinical, Social & Ethical, and Feasibility of Adoption within the system. All abstracts were included (regardless of position on evidence hierarchy) but only the full text of relevant studies where further detail was required was retrieved. No formal critical appraisal of studies was undertaken. Abstracts and full papers retrieved were used to create a narrative summary of the issues relevant to each domain and answer the specific research questions. If, after producing the narrative summaries for each domain the key research questions had not been addressed, further targeted searches using Google and Google scholar were undertaken. This strategy was used primarily to identify context-specific information required to answer questions in the ‘societal and ethical’ and ‘feasibility of adoption within the system’ domains and included New Zealand-specific information on immunisation coverage, as well as an investigation of other vaccines on the horizon. 24. The results of an economic evaluation provided to the Ministry of Health’s immunisation team on 20 January 2012 were critically appraised and used to provide contextualised answers to the cost-effectiveness questions posed in the economic domain. Summary of findings Clinical Domain (includes safety & effectiveness of vaccine and workforce considerations) National Health Committee April 2012 Page 4 of 16 Committee Report number: 2012022 25. Overall, current evidence suggests that both rotavirus vaccines available in New Zealand (Rotarix & RotaTeq) are safe and effective for use in most infants, alongside existing immunisations on the schedule. While there were initial concerns around the clinical safety of early rotavirus vaccines related to the heightened risk of intussusception (Rotashield), large phase III pre-licensure clinical trials of Rotarix and RotaTeq vaccines have not detected an increased risk (though post marketing surveillance indicates the possibility of a slightly increased risk shortly after the first dose in some populations). 26. Vaccines are prescription medicines, so they can only be administrated by medical practitioners, registered midwives, designated prescribers (including registered nurses), and people authorised to administer the medicine in accordance with a standing order. Given that it is proposed for the rotavirus vaccine to be given alongside existing vaccines on the schedule, no significant workforce implications are envisaged from a delivery perspective. However, there may be workforce implications from implementing the surveillance program that needs to accompany the roll-out of the vaccine. Economic Domain (value for money – ie, cost-effectiveness) 27. A three or two dose universal rotavirus vaccination program will increase health sector costs rather than decrease them (ie, the program will not result in cost-savings). The costeffectiveness of the program to the health payer is influenced by the price of the vaccine, and number of doses. 28. The annual medical costs incurred from rotavirus are estimated to be around $3.0 million, and if the assumptions of the economic model are correct, spending $7.9 million on a three-dose universal rotavirus vaccination programme for infants could save $2.3 million in medical costs (75% of total medical costs for rotavirus). 29. It is also anticipated that the annual number of rotavirus cases will decrease by 68% (from 60,000 to 19,050), and the number of cases requiring general practice and hospital care is expected to decrease by 78% (from 7,020 to 1,526) and 87% (from 900 to 114), respectively. Each year, a universal rotavirus vaccination programme could also result in the gain of 116 quality adjusted life years (QALYs). 30. In the New Zealand model, a three dose universal rotavirus vaccination programme was estimated to cost $62,000 per QALY gained. 31. In this scenario, universal rotavirus vaccination only became cost-saving to the health payer when the price of each dose of the vaccine decreased by more than half (from $50 to $15). 32. No studies were retrieved during the systematic search which explored the cost-effectiveness of reducing the number of doses, and the New Zealand evaluation did not investigate this. However, all cost-utility analyses retrieved comparing the cost effectiveness of two dose (Rotarix) versus three dose (RotaTeq) brands found that the 2 dose brand was more costeffective than the three dose brand. 33. The cost-effectiveness of the program to the health sector may also be improved if the costs of nosocomial5 infection were included in the analysis. However, results are still unlikely to be cost-saving to the health payer. 34. Some work has occurred in Canada suggesting that an immunisation strategy that targets patients at high risk of nosocomial rotavirus (such as infants with congenital pathology and low birth weight) may be more cost-effective than universal vaccination. The authors suggested that countries yet to introduce universal vaccination should assess targeted 5 A nosocomial infection is one acquired in hospital. No data on the incidence of nosocomial rotavirus infection in New Zealand was readily available, but if rates are similar to Canada, the incidence may be around 0.30 per 100 hospital admissions (see Verhagen P, Moore D, Manges A, Quach C. Nosocomial rotavirus gastroenteritis in a Canadian paediatric hospital: Incidence, disease burden and patients affected. Journal of Hospital Infection 2011;79 (1):59-63) National Health Committee April 2012 Page 5 of 16 Committee Report number: 2012022 vaccination. However, the authors stopped this work after most Canadian provinces and territories implemented a universal vaccination strategy. No other studies looking at targeted rotavirus vaccination could be identified (Appendix 1). 35. While rotavirus vaccination appears to be the preferred prevention method for nosocomial rotavirus infection, there are other effective prevention methods and the relative costeffectiveness of a vaccination strategy should be compared with these, particularly given their potential to reduce other hospital infections. For instance, breastfeeding (symptoms are less severe in breast fed infants), passive immunisation with antibodies, changes to hospital infection control interventions, and the use of probiotics, including administration of Lactobacillus GG (LGG) (Appendix 1). 36. If rotavirus vaccination was going to be used specifically to address nosocomial infections, the cost-effectiveness of this prevention method should be compared with other prevention methods first which would be the subject of a separate assessment. Societal & Ethical Domain (including acceptability and equity) 37. There is insufficient qualitative research to determine how New Zealand health practitioners and the public would prioritise a universal rotavirus vaccination programme in New Zealand. Further sociological research into public perceptions and prioritisation of vaccines, and new interventions generally in New Zealand, is necessary for this domain do be addressed adequately. 38. However, evidence from overseas and the coverage rates for existing vaccines on the New Zealand schedule suggest that rotavirus vaccination may not be perceived as a high priority for public funding-– particularly in the context of disparities in coverage for existing publiclyfunded immunisations and the high incidence of other infectious diseases. 39. Internationally, rotavirus vaccination is prioritised lower than other vaccines by health practitioners (including the chickenpox vaccine) and continues to have lower uptake than vaccines currently on the schedule. 40. It has also been suggested that the addition of yet another vaccine in this age-group may not be acceptable to the public. However, as it is delivered orally, it may be more feasible and acceptable to parents than vaccines that require an injection (eg, varicella). 41. Similar issues and examples discussed in the varicella recommendations paper are also relevant here (NHC paper # 2012021 refers). Financial Domain (includes feasibility of adoption and budget impact) 42. There are significant costs in implementing a vaccination program, not all of which were captured in the economic model, and many of which are difficult to estimate – hindering a determination of whether the vaccine is affordable and feasible to adopt. 43. In addition to the annual cost of the vaccine and administration/delivery costs (considered in the economic model), there are also costs associated with education and promotion, and compliance and surveillance, as well as additional one-off set-up costs associated with the supply chain (which were not considered in the economic model). Estimates of some of these costs are provided in Table 2. Table 2: Estimated annual costs of delivering a universal rotavirus vaccination programme with 100% uptake. Item Rotavirus vaccine (wholesale – excl GST & freight) National Health Committee April 2012 Cost Cost per Cost per Source per person cohort dose $50.00 $150.00 $9,000,000.00 Manufacturers (2012) Page 6 of 16 Committee Report number: 2012022 Administration/delivery costs (2007/08) $25.67 Surveillance and service audit, and research and evaluation6 n/a Promotion & advertising7 n/a Total $75.67 $77.01 $4,620,600.00 Immunisation Advisory Centre1 n/a $500,000.00 Health Report number: 20110143 n/a $100,000.00 Health Report number: 20110143 $227.01 $14,220,600 Note: Items highlighted grey are confidential and not for public dissemination. 44. Prior to implementation a comprehensive surveillance system will need to be established to monitor waning immunity, changing dominance of specific rotavirus strains and the risk of intussusception. The costs to, and burden on, the health sector of setting up a new system, or making rotavirus a notifiable diseases under the existing system have not been included in the current evaluation of cost-effectiveness. Once these costs are included, the costeffectiveness of universal vaccination is likely to further decrease from the perspective of the health payer, and place additional pressure on District Health Boards (DHBs) and labs. 45. DHBs also experience costs associated with ensuring adequate uptake through the use of out-reach services, which are estimated to cost between $250 and $1000 per hard to reach child. As the rotavirus vaccine would be delivered at the same time as existing vaccines, outreach costs would not increase. However, the failure to factor these costs into initial decisions about the addition of existing vaccines on the immunisation schedule may mean DHBs are currently resourcing activities they are not being adequately reimbursed for. 46. Currently, information on the costs associated with the supply chain for vaccines (including rotavirus) are unknown and often these costs are identified after a decision to add a vaccine to the schedule has been made. In the future all the costs associated with delivering a new vaccine program need to be identified prior to undertaking an economic evaluation of its costeffectiveness so that its funding can be prioritised accurately. 47. The exclusion of these costs from the economic evaluation and prioritisation of vaccines is not a shortcoming unique to New Zealand – these costs are often not identified in assessments overseas. However, in order to adequately assess whether different parts of the system have sufficient slack to absorb the addition of subsequent vaccines, a framework that accounts for these costs and adjusts accordingly, is required. 48. Furthermore, it will be important for future economic evaluations of vaccines in New Zealand to use a standard model that adequately reflects the impact of herd immunity and transmission dynamics of infectious diseases which can influence the cost-effectiveness of vaccines. 49. The whole process of assessing, prioritising and procuring new vaccines in New Zealand is currently the subject of a policy paper being developed in the Policy Business Unit of the Ministry of Health so the actual procurement process at this stage is uncertain. 6 7 This is based on an estimate for the rheumatic fever programme. More accurate data should be located. This is based on an estimate for the rheumatic fever programme. More accurate data should be located. National Health Committee April 2012 Page 7 of 16 Committee Report number: 2012022 Social economic benefit 50. The cost-effectiveness of a universal rotavirus vaccination program is greater from a societal perspective than a health payers perspective but is still not cost saving. From a societal perspective, the programme would return $0.97 in productivity savings for every dollar spent. 51. Each year, rotavirus costs the New Zealand economy approximately $8.3 million through lost productivity as a result of parental time spent caring for sick children instead of working, and loss of future earnings through death. 52. If the assumptions of the model are correct, spending $7.9 million on a universal rotavirus vaccination programme for infants could save $6 million in lost productivity (72% of total productivity costs). Limitations and uncertainty 53. The conclusions drawn in the societal and ethical domain were not informed through engaging directly with New Zealand health practitioners and public but were based on coverage rates for existing vaccines and evidence from overseas. 54. The economic evaluation was not informed by a systematic review and critical appraisal of the evidence on clinical safety and effectiveness, but was based on the expertise of the Immunisation Technical Forum (ITF). 55. The economic evaluation did not include all costs associated with implementation – including surveillance and promotion/education and the coverage parameters for vaccination may have been optimistic. It is also unclear how sensitive the results are to a reduction in the number of doses (from three to two). 56. It is unclear how ‘real’ the societal savings are, and if they do exist, whether it is appropriate for Vote: Health to fund the costs of the program when the majority of the benefits accrue elsewhere. 57. The actual price of the vaccine is unknown until a decision is made to adopt the universal vaccination program and negotiations commence. Prioritisation 58. An additional consideration is whether a universal rotavirus vaccination programme would be the best use of public money when compared with other potential spending in the space of vaccines, infectious diseases and child health more broadly which may generate greater health gains and result in cost-savings to the health system. 59. A three dose rotavirus vaccination programme is less cost-effective (ie, it would return lower health gains for the money spent) than a two dose varicella vaccination programme. While the crude incidence and mortality rate for rotavirus is less than varicella, the hospitalisation rate is nearly five times higher. 60. Rather than funding the addition of either vaccine to the schedule the money may be better spent on increasing coverage rates for existing vaccines on the schedule (including among ‘hard to reach’ population groups), saved to fund other, potentially more beneficial vaccines on the horizon, or spent in other areas of child health which are likely to produce greater health gains. Performance against criteria 61. Overall, the public funding of universal rotavirus vaccination of children does not perform well when evaluated against the Committee’s decision-making criteria. Of the eleven criteria, the intervention only met ‘well’ or ‘very well’ the criteria for clinical safety and effectiveness and National Health Committee April 2012 Page 8 of 16 Committee Report number: 2012022 ‘risk’. It ‘somewhat’ met the criteria of health and independence gain, but did not meet very well the criteria of materiality, feasibility, policy congruence, equity, acceptability, costeffectiveness or affordability (Figure 1). Figure 1: Evaluation of universal rotavirus vaccination against decision-making criteria with respect to the Vote: Health budget How well does the proposal fit the NHC's criteria? Criteria Not at all Not very well Somewhat Well Very Well Clinical Safety and Effectiveness Health and Independence Gain Materiality Feasibility Policy Congruence Equity Acceptability Cost Effectiveness (Value for Money) Affordability Risk Other Criteria as the NHC thinks fit. Explanation The available vaccines are clinically safe & effective in most cases. There is a health gain, but rotavirus is usually a relatively mild disease so the health gain is low er than for other interventions. There are productivity gains, but the gains to the health system are small. Increased surveillance burden on health sector and potential difficulties in achieving required coverage. Potential to distract from a focus on increasing immunisation coverage. Disease experienced similarly by different subgroups of the population but uptake of intervention, and thus benefits likely to be unequally distributed. Rotavirus is view ed as moderately severe and oral delivery (rather than injection) may appeal, but another vaccination in childhood may not be acceptable to the public particularly given overseas experience w ith Rotashield. Estimated to cost the health payer $62k/QALY gained and result in societal savings (from reducing parental time off w ork) of approx $6 million. Given other competing priorities this vaccine may not be affordable in the long-term. The risk of introducing the intervention is not more significant than the risk of not introducing the intervention. N/A Recommendation As the intervention does not perform well or very well against over half of the Committee’s criteria, it is suggested that they recommend that the Ministry of Health does not fund the universal vaccination of infants for rotavirus gastroenteritis. The net avoided costs from this recommendation would be $5.6 million per annum8, but the opportunity for a gain of 116 QALYs and savings of $6 million in lost productivity would be foregone. Note that the estimated net avoided costs are based on the economic evaluation which did not consider all the costs of the programme. This means that the net avoided costs are a conservative estimate and that the actual costs avoided are much higher. Criteria for review Every recommendation made by the NHC is subject to review if the evidence upon which the assessment and recommendations are based changes. The recommendation not to publicly fund a universal rotavirus vaccination programme for infants will be reviewed if the: 8 price of the vaccines reduce to less than $15.00 per dose or the severity of disease experience significantly increases or health care costs associated with rotavirus significantly increase or = Cost of vaccine ($7.9 million) – Cost of medical costs saved through vaccination ($2.3 million) National Health Committee April 2012 Page 9 of 16 Committee Report number: 2012022 public demand for the vaccine increases and coverage for existing vaccines on the schedule reaches recommended levels (ie, there is evidence that the vaccine is acceptable and a high priority to the public and the risk of a new vaccine affecting coverage for existing vaccines declines). END. National Health Committee April 2012 Page 10 of 16 Committee Report number: 2012022 Appendix 1: Summary of additional evidence requested 1. At the previous Committee meeting (26 March 2012) a draft of the Rotavirus assessment report was provided to the Committee as part of the ‘stage gate’ process of determining what further evidence the Committee requires prior to making a decision. 2. The Committee instructed the Executive to further investigate the impact of targeting vaccination to patients at high risk of nosocomial rotavirus gastroenteritis on the clinical- and cost-effectiveness of the programme. A limited ‘light’ literature search was suggested and the methods used for, and findings of this search are presented below. 3. On the 30 March 2012 the Ministry of Health reference librarians systematically searched Ovid MEDLINE® and Cochrane Library for all scientific journal papers published using the following search terms (and variations thereof): Rotavirus, vaccine, targeting, nosocomial infection, systematic review, health technology assessment, cost-effectiveness, vulnerable children. The full search strategy is provided in Appendix 2. 4. As this search only identified 20 papers, of which the only relevant one was the Canadian study that was identified previously during the main search, the authors of the Canadian study were approached to determine what further work they had undertaken and whether they were aware of any other studies. They had not completed any further work and were unaware of other studies (email correspondence supplied in Appendix 2). 5. On the 2 April 2012 the Ministry of Health reference librarians systematically searched Ovid MEDLINE® and Cochrane Library for all commercial journal papers published using similar search terms as above but widening the search to include the most clinically and costeffective method for the prevention of nosocomial infections in hospitals. 6. While none of the 77 studies identified were comparative studies that definitively stated which was the most clinically or cost-effective method, abstracts of some of these papers suggest that there are a number of clinically effective alternatives for the prevention of nosocomial infections that may be more cost-effective than universal rotavirus vaccination. 7. Alternatives to rotavirus vaccination for the prevention of nosocomial rotavirus infection include: a. Changes to hospital infection control interventions, including hand washing, gloves, isolation etc2-5 a. Breast milk and promotion of breast feeding (symptoms are less severe in breast fed infants) 5-8 b. Passive immunisation with antibodies including bovine colostrum and gammaglobulin5,9,10 c. The use of probiotics, including administration of Lactobacillus GG (LGG)5,11-14 d. Increased awareness of undiagnosed transmissible diseases15,16 8. Mrukowicz et al5 (2008) summarised the evidence on the non-vaccine options available for the prevention of Rotavirus infection. They concluded that improvements in sanitation and hand-washing were shown to have limited benefit and that while passive immunisation had been used successfully for rotavirus gastroenteritis (RVGE) prevention in hospitals, no commercial preparations were available. They also concluded that while probiotics had shown promise, cost-effectiveness analyses were still required, and that while breast feeding is recommended, it appears to postpone rather than prevent RVGE. Next steps 9. To determine which method is most cost-effective would require another/separate economic evaluation and additional HTAs in order to assess these interventions against the Committee’s other domains and decision-making criteria (including clinical effectiveness and feasibility of adoption). National Health Committee April 2012 Page 11 of 16 Committee Report number: 2012022 10. Prior to doing this it would also be necessary to determine whether the epidemiological and financial burden of nosocomial rotavirus infection in New Zealand was significant enough to dedicate assessment resources to – this may require primary data analysis due to the absence of this data in the literature. National Health Committee April 2012 Page 12 of 16 Committee Report number: 2012022 Appendix 2: Search strategies, email correspondence and references relating to additional evidence. SEARCH STRATEGIES 1. Search Run on 30-March-2012 Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations and Ovid MEDLINE(R) <1946 to Present> Search Strategy: -------------------------------------------------------------------------------1 rotavirus OR rotarix OR rotateq.mp OR ("rix4414" or rix4414).mp OR "wc-3".mp 2 exp rotavirus/ 3 exp rotavirus infections/ 4 exp rotavirus vaccines/ 5 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 6 exp vaccines/ 7 vaccin*.mp. 8 5 and (6 or 7) 9 target*.mp. 10 Vulnerable Populations/ 11 (vulnerabl* adj3 (child* or infant* or toddler or baby or babies)).mp. [mp=title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, protocol supplementary concept, rare disease supplementary concept, unique identifier] 12 8 and (9 or 10 or 11) 13 5 and target*.mp. and universal*.mp. [mp=title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, protocol supplementary concept, rare disease supplementary concept, unique identifier] 14 12 or 13 15 economic evaluation*.mp. 16 Cost-Benefit Analysis/ 17 cost effectiveness analys*.mp. 18 cost utility.mp. 19 Models, Economic/ 20 decision analys*.mp. 21 "Costs and Cost Analysis"/ 22 systematic review*.mp. 23 health technol*.mp. 24 Technology Assessment, Biomedical/ or assessment.mp 25 Risk Factors/ or Risk/ or Risk Assessment/ 26 14 and (15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25) *************************** Cochrane Library Current Search History ID Search Hits Edit Delete #1 MeSH descriptor Rotavirus explode all trees #2 MeSH descriptor Rotavirus Infections explode all trees #3 MeSH descriptor Rotavirus Vaccines explode all trees #4 (rotavirus):ti,ab,kw 429 National Health Committee April 2012 Page 13 of 16 Committee Report number: 2012022 #5 (target*):ti,ab,kw or (vulnerable):ti,ab,kw #6 (#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4) 429 #7 (#5 AND #6) 2 2. Search Run on 2 April 2011 Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations and Ovid MEDLINE(R) <1946 to Present> Search Strategy: -------------------------------------------------------------------------------1 exp Gastroenteritis/pc (4723) 2 Rotavirus Infections/pc [Prevention & Control] (1262) 3 child/ or child, preschool/ or infant/ (1587987) 4 Cross Infection/ (41380) 5 (nosocomial adj2 infection*).ab,ti. (9599) 6 (hospital adj2 acquired).ab,ti. (4473) 7 (1 or 2) and 3 and (4 or 5 or 6) (72) *************************** Cochrane Library #1 MeSH descriptor Gastroenteritis explode all trees with qualifier: PC 406 #2 MeSH descriptor Rotavirus Infections explode all trees with qualifier: PC 178 #3 (#1 OR #2) 522 #4 MeSH descriptor Cross Infection explode all trees 1104 #5 (nosocomial infection*):ti,ab,kw or (hospital acquired):ti,ab,kw 972 #6 (#4 OR #5) 1783 #7 (#3 AND #6) 26 #8 (child*):ti,ab,kw or (infant*):ti,ab,kw or (newborn*):ti,ab,kw or (toddler*):ti,ab,kw or (bab*):ti,ab,kw 78159 #9 (#7 AND #8) 16 EMAIL CORRESPONDENCE I haven't come across anyone else looking at targeted RV immunization. The only country that may be looking at different strategies is The Netherlands. My graduate student at the time, Patricia Verhagen (now Bruijning) is now back at Utrecht University and is continuing the work... that we are not able to do anymore in Canada, as most provinces and territories have now implemented universal RV vaccination using RV1. In the Province of Quebec, where we tend to look at different strategies, we were actually planning a RCT to determine the vaccine effectiveness of a 1-dose rotavirus vaccination program (vs. placebo) and were ready to submit to science and ethics when GSK came in a bid in the next door province (Ontario) with a price below what we had calculated to be cost-neutral. As we were able to use the federal purchasing service and get the vaccine at the same price as Ontario, it was decided to put the study on hold and take the full-dose RV program using RV1. And there went all our research possibilities. The universal vaccination program was launched in Quebec on November 1st, 2011 and the uptake seems excellent. The current RV season has been quite mild so far (and that's using active surveillance!). Patricia Verhagen's email is: p.bruijning@umcutrecht.nl<mailto:p.bruijning@umcutrecht.nl> National Health Committee April 2012 Page 14 of 16 Committee Report number: 2012022 Best of luck in your decisions. Do not hesitate to contact me if I can be of further assistance. Regards, Caroline _________________________________ Caroline Quach, MD MSc FRCPC Pediatric Infectious Diseases and Medical Microbiologist | The Montreal Children's Hospital Associate Professor of Pediatrics | McGill University P +1-514-934-1934 ext. 22620 F +1-514-412-4494 Email: caroline.quach@mcgill.ca<mailto:caroline.quach@mcgill.ca> On 2012-04-01, at 8:03 PM, Dear Caroline, I have recently read with interest an abstract of a paper your co-authored titled " Nosocomial rotavirus gastroenteritis: Possible impact of a targeted immunization strategy" (2010) in which you suggest that a targeted rotavirus vaccination program (for specific high risk patients), may be a cost-effective alternative to universal vaccination. Following this paper you published another paper in 2011 which concluded that " A rotavirus immunisation programme targeted at vulnerable patients, such as infants with congenital pathology and low birth weight, requires assessment in Canada and other countries that have not introduced universal rotavirus immunisation". New Zealand is one such country that is yet to implement universal rotavirus vaccination, and I was wondering whether you were aware of any papers in progress that are assessing a targeted vs universal approach overseas? We have conducted a fairly comprehensive literature search for papers comparing a targeted versus universal approach to rotavirus vaccination, but your two papers are the only ones retrieved that were relevant (and only an abstract was publicly available for the 2010 paper). Any information (including full text for the 2010 abstract), would be much appreciated. Kind regards, National Health Committee Ministry of Health (New Zealand) DDI: 04 816 4415 National Health Committee April 2012 Page 15 of 16 Committee Report number: 2012022 REFERENCES 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. Immunisation Advisory Centre. The Cost of Immunising in General Practice. Vol. 2012 University of Auckland, 2012. Gallimore CI, Taylor C, Gennery AR, Cant AJ, Galloway A, Xerry J, Adigwe J, Gray JJ. Contamination of the hospital environment with gastroenteric viruses: comparison of two pediatric wards over a winter season. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 2008;46(9):3112-5. Hjelt K. [Nosocomial virus infections in pediatric departments. Rotavirus and respiratory syncytial virus]. Ugeskrift for Laeger 1991;153(30):2102-4. Kordidarian R, Kelishadi R, Arjmandfar Y. Nosocomial infection due to rotavirus in infants in Alzahra Hospital, Isfahan, Iran. Journal of Health, Population & Nutrition 2007;25(2):231-5. Mrukowicz J, Szajewska H, Vesikari T. Options for the prevention of rotavirus disease other than vaccination. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology & Nutrition 2008;46 Suppl 2:S32-7. Berger R, Hadziselimovic F, Just M, Reigel F. Influence of breast milk on nosocomial rotavirus infections in infants. Infection 1984;12(3):171-4. Berger R, Hadziselimovic F, Just M, Reigel P. Effect of feeding human milk on nosocomial rotavirus infections in an infants ward. Developments in Biological Standardization 1983;53:219-28. Mastretta E, Longo P, Laccisaglia A, Balbo L, Russo R, Mazzaccara A, Gianino P. Effect of Lactobacillus GG and breast-feeding in the prevention of rotavirus nosocomial infection. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology & Nutrition 2002;35(4):527-31. Davidson GP, Whyte PB, Daniels E, Franklin K, Nunan H, McCloud PI, Moore AG, Moore DJ. Passive immunisation of children with bovine colostrum containing antibodies to human rotavirus. Lancet 1989;2(8665):709-12. O'Brien K, Donato R. Hospital acquired rota virus infection: the economics of prevention. Australian Health Review 1993;16(3):245-67. Guandalini S. Probiotics for children: use in diarrhea. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 2006;40(3):244-8. Szajewska H. Probiotics and prebiotics in pediatrics: where are we now? Turkish Journal of Pediatrics 2007;49(3):231-44. Szajewska H, Kotowska M, Mrukowicz JZ, Armanska M, Mikolajczyk W. Efficacy of Lactobacillus GG in prevention of nosocomial diarrhea in infants. Journal of Pediatrics 2001;138(3):361-5. Hojsak I, Abdovic S, Szajewska H, Milosevic M, Krznaric Z, Kolacek S. Lactobacillus GG in the prevention of nosocomial gastrointestinal and respiratory tract infections. Pediatrics 2010;125(5):e1171-7. Scheithauer S, Oude-Aost J, Stollbrink-Peschgens C, Haefner H, Waitschies B, Wagner N, Lemmen SW. Suspicion of viral gastroenteritis does improve compliance with hand hygiene. Infection 2011;39(4):359-62. Zerr DM, Allpress AL, Heath J, Bornemann R, Bennett E. Decreasing hospital-associated rotavirus infection: a multidisciplinary hand hygiene campaign in a children's hospital. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 2005;24(5):397-403. National Health Committee April 2012 Page 16 of 16