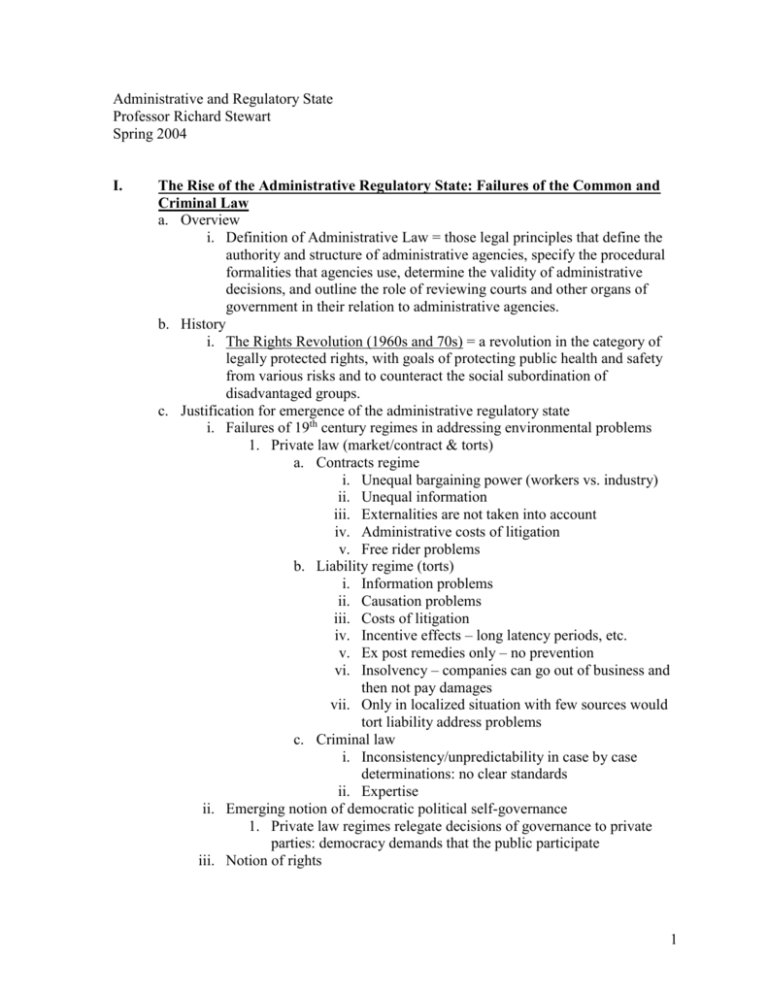

Administrative and Regulatory State

advertisement