Teaching Reusable Vocabulary In Academic Settings

advertisement

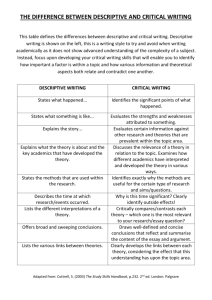

Teaching Reusable Vocabulary In Academic Settings Baker, B. Abstract. One of the most significant ways people connect with their communities is through the education process. However, one of the most baffling problems in the use of augmentative communication technology results from this education process. This presentation discusses ways to use core vocabulary for academic purposes with augmented communicators. The populations of augmented communicators include children and adults with cognitive impairments as well as students who use their systems in inclusionary settings. The emphasis will be on how speech clinicians, special educators, and technologists can collaborate to combine meaningful language based on core vocabulary with a participation model for the classroom. Currently, subject matter words are added on a daily or weekly basis often totaling hundreds of words annually to the vocabularies of communication aid users. Many of these words are not used again after a particular classroom assignment or test is completed. 1 Introduction: Supporting Teachers of Augmented Communicators Augmentative communication technology is an important means of connecting people with their community education systems. In various countries and districts, funding for augmentative communication is provided by school systems. Much student/clinician/faculty contact time is devoted to inputting academic vocabulary that is only temporarily useful. This presentation discusses ways of using core/reusable vocabulary in academic settings to save time and promote language development. Teachers hold the keys to augmentative communication success in the schools. Clinicians—speech language pathologists (SLP), occupational therapists (OT), physical therapists (PT), etc.—teacher’s aids, tech aids, personal assistants are there to support the educational process, which is essentially driven by the teaching staff. 2 The Problem: Referential Questions and Answers Teachers need to have a fluid, up-to-date knowledge of what students have learned. It is very difficult to teach without knowing where students are in the learning process. Do they have cognitive charity about what they are supposed to be learning? Are they engaged in the process? Teachers monitor cognitive clarity, engagement, and student progress through asking questions. For efficiency, questions are phrased to elicit short answers. “Name three animals we saw on our walk.” “What’s this?” “Name the largest planet.” Referential, often one word, response-oriented structures are used for testing. Such referential-style questions are efficient and elicit targeted responses that give teachers a profile of student progress. Question and answer sessions refresh student memory as well as provide another teaching of the original information. While referential style questions are a natural and often effective method for monitoring the class and individual learning status, they are not necessarily helpful linguistically or academically for augmented communicators. Referential style questions force augmented communicators to have specialized vocabularies. These vocabularies change frequently on a daily, weekly or monthly basis and can feature hundreds of words each year. Putting in single word or brief sentence responses in a referential context takes a significant amount of time. Below is a selection from ACOLUG—Augmentative Communication Online Users Group—a listserv at Temple University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. This listserv is open to augmentative communicators, their families, their teachers, and other professionals. The quotation below is several years old and all identifying material has been removed. Subject: Who programs the speech-generating device (SGD)? I am fairly new to this chat organization. I read with concern about the problems that arise with programming…[SGDs]. As an SLP with two students who have the older versions of [an SGD], I have spent hours upon hours programming the devices at home. The IEP states specified time periods which are devoted to student contact time with the devices. The devices are also used in the classrooms when I am not present. My concern last school year, as it is now, is how much time can I spend programming devices at home without alienating my family. Last year I kept track of the hours I worked at home and it totaled well over 300 hours which was more than 12 work weeks. I, too, am frustrated. I spoke with the principal at my school and together we agreed that it was necessary for me to incorporate some non-student contact time into my schedule so that I could do some programming on the job. This year I have scheduled Friday afternoons to program devices and work on other AAC needs within the school building. So far this year, I have had 5 Friday afternoons to do this work. Many Fridays there was no school or else other specials were in place. The biggest problem with programming is time. Therapists would probably be more than happy to program devices if time was available but typically the caseloads are quite large and it almost seems impossible to schedule all the students at the beginning of the year. It really is a dilemma. Hundreds of hours are used in programming context specific, academic vocabulary. The load is enormous and leads to the perception that augmentative communication is not worth the burden it places on staff and family. The amount of time consumed in such activities also takes away from language learning and teaching. Rather than learning how to communicate, a student and his/her team invests their time together in selecting, adding, and learning new words. These words may never be used again by the student. However, if such amounts of programming time were successful and this SLT’s students were making progress and communicating independently, such sacrifices would be understandable. Yet the next letter in this thread reveals the true situation. Subject: Who programs the speech generating device (SGD)? With the [SDGs], there is a large chance that the programming will take on a life of its own…However, here are a couple of thoughts to add to the mix. To set the stage, I am speaking about a young man, J., age 20 with CP and other disabilities, who uses [an SGD]. He was attending an integrated high school program last year with an individual paraprofessional, B., who was with him most of the time. I am an SLPAAC consultant, and am at their high school one afternoon each week. J. has since graduated. J., B., and I met weekly. I would provide direction/feedback and offer ideas, and give examples. I would also troubleshoot problems and try to resolve anything that needed resolution. B. would program with J., who would give lots of non-verbal input into things like vocabulary choices, icon selection, icon location and wording. J. and B. would sit together for at least one study hall per day. They would do…programming… Is there a way to calculate the number of hours [spent programming], …and have the school commit to providing the programming services as a “related service” in [the] IEP? It is not like you are asking them to keep up with what…is [needed] to say at home. The bulk of the programming time is relating to school subjects and activities, right? Here again, we see that an enormous amount of time is spent programming new vocabulary. Notice in bold print that “J. has since graduated.” Who is doing his programming now? Is he communicating independently? Apparently not—J. gives lots of “non-verbal input into things like vocabulary choices, icon selection, icon location and wording. 3 The Failure of the Referential Language Model The perceived burden of AAC and its regular failure to provide students with independent communication abilities can, in this author’s opinion, be attributed to the referential language model for AAC students in school settings. Referential responses imply an unending set of special pages for words that support class and activity participation. Most referential words on the special pages are useful in classrooms or activities for a limited period of time (one day - one week). Hundreds of hours per year may be devoted to configuring academic and activity-based pages. Years of school require the programming of thousands of “temporary words.” These words are designated “temporary,” because they quickly become expressively unavailable. Although referential vocabulary is currently used in most educational settings, its labor-intensive nature and massive inefficiency mark it as a target for a simpler, more efficient approach. Rather than targeting specific “temporary words,” students could be asked to show their knowledge by giving information about the target or referential word. A teacher can phrase the question with the referential word and ask for information about the word, named object, name, or concept. “Informational” or “descriptive” responses can replace referential responses in many school setting. The student can provide information using vocabulary from his or her “permanent words”—core vocabulary. 4 The Descriptive Method In the descriptive method, core vocabulary words—300 to 400 most commonly occurring lexemes—are used instead of specific names. The command “Name three animals we saw on our walk” is replaced by “Tell me something about a squirrel.” Descriptive responses might be “They run around,” “They are fast,” “We saw one on our walk,” or “They eat things that fall down.” The student learns to use his or her permanent vocabulary words in meaningful and rewarding ways. The role of the speech therapist is two fold. First, assist the teacher in phrasing questions for descriptive rather than referential responses. The second would be teaching the student the reusable core words he or she will need to make responses. Thus, the speech therapist’s role is transformed from one of constant system design to expressive language teaching. The descriptive method is less labor intensive for teachers and clinicians because students use their permanent vocabularies. The programming of new words can be kept to a minimum, while learning to use common words independently in variety of situations is stressed. New pages do not have to be programmed for each activity. Activity-based learning in school and other teaching settings includes bed making, cooking, cleaning up, art, decorating for a holiday, playing a game, reading a book, etc. It is possible to use simple, frequently used words—core vocabulary—as a basis for interaction during learning and independent-living activities at all levels. For example, ‘pull,’ ‘take,’ ‘push,’ ‘turn,’ ‘clean ‘get,’ ‘in,’ ‘out,’ ‘off,’ ‘on,’ ‘back,’ ‘up,’ ‘down,’ ‘it,’ ‘them,’ ‘that,’ ‘this,’ ‘those,’ ‘these’ are useful words across many activities and environments. In a bed-making activity, ‘Take it off,’ ‘Put it on,’ ‘Pull it down,’ can replace ‘mattress,’ ‘sheet,’ ‘pillow case,’ and ‘mattress pad,’. In a kitchen-based activity, participation words like ‘skillet,’ ‘spatula,’ ‘cooker,’ ‘mix,’ ‘pour,’ ‘stir’ can be replaced by subject-verb-object language like ‘Turn it on,’ ‘Take it off, ‘Turn it up,’ ‘Turn it down,’ and ‘Clean it off.’ The role of the augmented communicator can be to describe simple actions and describe what to do next without using referential, “temporary” vocabulary. While it is important for special education students to learn the meanings of referential vocabulary, it is not necessary for them to be burdened by storing and learning how to access these words. A revolving referential vocabulary is difficult to learn for many special education students. Referential words regularly become hidden after the specific activity has stopped and are unavailable for the student to use spontaneously in his or her daily life. It is simpler and more consistent for the staff to teach students to make short combinations of words they already know: ‘Clean it up,’ ‘Turn it over,’ ‘Turn it up,’ ‘Turn it down,’ etc. The descriptive method is less labor intensive for teachers and clinicians because students use their permanent vocabularies. A descriptive answer often provides the teacher with better feedback concerning a student’s progress than a one word or preprogrammed reply. The descriptive method satisfies conventional teaching goals better, because it allows students to communicate comprehension. A short phrase, independently constructed, demonstrates understanding and can reveal studentlearning strategies. It allows students to make connection and raise questions. Conceptual understanding is more assessable through short, descriptive utterances. Referential answers are typically pre-programmed by staff and may not represent the students real learning and intentionality.