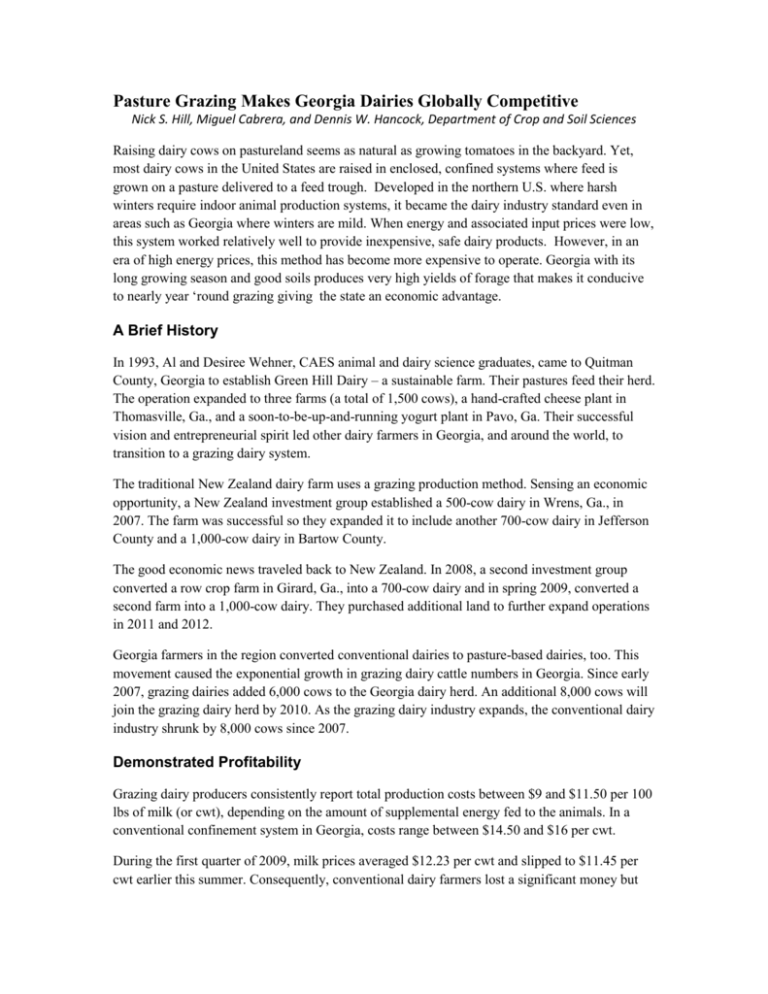

Pasture Grazing Makes Georgia Dairies Globally Competitive

advertisement

Pasture Grazing Makes Georgia Dairies Globally Competitive Nick S. Hill, Miguel Cabrera, and Dennis W. Hancock, Department of Crop and Soil Sciences Raising dairy cows on pastureland seems as natural as growing tomatoes in the backyard. Yet, most dairy cows in the United States are raised in enclosed, confined systems where feed is grown on a pasture delivered to a feed trough. Developed in the northern U.S. where harsh winters require indoor animal production systems, it became the dairy industry standard even in areas such as Georgia where winters are mild. When energy and associated input prices were low, this system worked relatively well to provide inexpensive, safe dairy products. However, in an era of high energy prices, this method has become more expensive to operate. Georgia with its long growing season and good soils produces very high yields of forage that makes it conducive to nearly year ‘round grazing giving the state an economic advantage. A Brief History In 1993, Al and Desiree Wehner, CAES animal and dairy science graduates, came to Quitman County, Georgia to establish Green Hill Dairy – a sustainable farm. Their pastures feed their herd. The operation expanded to three farms (a total of 1,500 cows), a hand-crafted cheese plant in Thomasville, Ga., and a soon-to-be-up-and-running yogurt plant in Pavo, Ga. Their successful vision and entrepreneurial spirit led other dairy farmers in Georgia, and around the world, to transition to a grazing dairy system. The traditional New Zealand dairy farm uses a grazing production method. Sensing an economic opportunity, a New Zealand investment group established a 500-cow dairy in Wrens, Ga., in 2007. The farm was successful so they expanded it to include another 700-cow dairy in Jefferson County and a 1,000-cow dairy in Bartow County. The good economic news traveled back to New Zealand. In 2008, a second investment group converted a row crop farm in Girard, Ga., into a 700-cow dairy and in spring 2009, converted a second farm into a 1,000-cow dairy. They purchased additional land to further expand operations in 2011 and 2012. Georgia farmers in the region converted conventional dairies to pasture-based dairies, too. This movement caused the exponential growth in grazing dairy cattle numbers in Georgia. Since early 2007, grazing dairies added 6,000 cows to the Georgia dairy herd. An additional 8,000 cows will join the grazing dairy herd by 2010. As the grazing dairy industry expands, the conventional dairy industry shrunk by 8,000 cows since 2007. Demonstrated Profitability Grazing dairy producers consistently report total production costs between $9 and $11.50 per 100 lbs of milk (or cwt), depending on the amount of supplemental energy fed to the animals. In a conventional confinement system in Georgia, costs range between $14.50 and $16 per cwt. During the first quarter of 2009, milk prices averaged $12.23 per cwt and slipped to $11.45 per cwt earlier this summer. Consequently, conventional dairy farmers lost a significant money but hoped they would see prices rebound. Pasture-based dairies saw first-quarter profits between $2.70 and $3.25 and most maintained this profitability during the summer. To be profitable even during a severe market downturn makes grazing an appealing option for Georgia dairy producers. Georgia’s Strategic Geographical Location The amount of milk produced by the Georgia dairy industry won’t meet the population’s needs. The same is true of states across the Southeast. The state is strategically located to be a production and distribution hub for other milk deficient states. Being a milk exporter, rather than a milk importer will build Georgia’s rural economy. University of Georgia research shows that for each 1,000-cow dairy farm developed in Georgia about $2 million in local and state tax revenue is generated. Once farms become operational, about $700,000 in local and state revenue is generated from milk sales. The number of cows on grazing dairies should generate about $11.2 million in annual tax revenue. Environmental and Social Benefits Pasture-based dairies are efficient water users and cause no air quality problems. Tifton 85 bermudagrass, often a staple pasture grass, is 67 percent more water efficient than corn. Air quality around pasture-based dairies is exceptional, with little foul odor or particulate matter. Research conducted by UGA professors Nick Hill, Miguel Cabrera, Dennis Hancock, and David Kissel and graduate student Nathan Eason show minimal nutrient releases and greenhouse gas emissions from grazing dairy farms. Nitrate leaching and runoff from confinement-based dairies in Florida contribute 27 percent of the total nitrogen in the Suwannee River. A whole farm approach was used in assessing nitrogen inputs from feed and fertilizer and losses in exported milk, nitrate leaching, nitrous oxide emissions and ammonia volatilization. Nitrate leaching and nitrous oxide emissions represented 0.28 and 2.7 percent of the total nitrogen imported onto the farm. Nitrogen transformations in the pasture-based system didn’t significantly contribute to ground water pollution or greenhouse gas emissions. Nitrogen efficiency use was 70 percent, far greater than corn silage’s 45 percent. Nutrients can be distributed on intensively managed pastures, with less than 5 percent of the total animal waste ending up in a nutrient containment facility. Unfortunately, the average American’s diet has been linked to major human health risks such as heart disease, obesity and diabetes. Dairy products from pasture-based dairies can help offset many risks. Milk from grazing dairy cows is high in omega-3 fatty acids, conjugated linolenic acids, and other compounds proven to improve cardiovascular health, curb hypo/hyperglycemia and prevent cancer. Many scientific studies show increasing milk consumption from pasturebased dairy cows is the most effective way to increase these beneficial compounds in the average American’s diet.