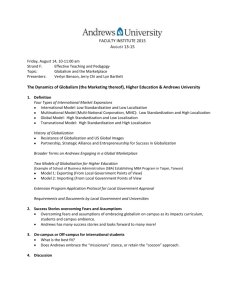

software localization: notes on technology and culture

advertisement