Comprehensive Test o.. - University of Alberta

advertisement

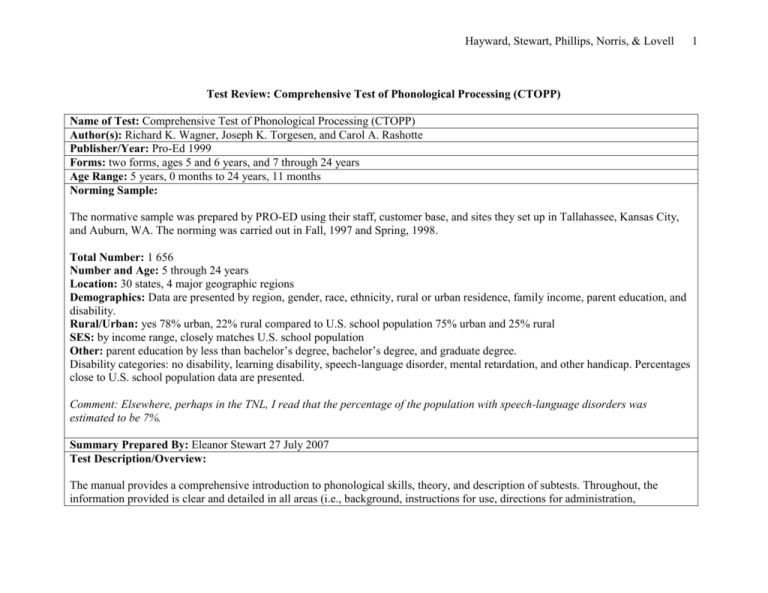

Hayward, Stewart, Phillips, Norris, & Lovell Test Review: Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing (CTOPP) Name of Test: Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing (CTOPP) Author(s): Richard K. Wagner, Joseph K. Torgesen, and Carol A. Rashotte Publisher/Year: Pro-Ed 1999 Forms: two forms, ages 5 and 6 years, and 7 through 24 years Age Range: 5 years, 0 months to 24 years, 11 months Norming Sample: The normative sample was prepared by PRO-ED using their staff, customer base, and sites they set up in Tallahassee, Kansas City, and Auburn, WA. The norming was carried out in Fall, 1997 and Spring, 1998. Total Number: 1 656 Number and Age: 5 through 24 years Location: 30 states, 4 major geographic regions Demographics: Data are presented by region, gender, race, ethnicity, rural or urban residence, family income, parent education, and disability. Rural/Urban: yes 78% urban, 22% rural compared to U.S. school population 75% urban and 25% rural SES: by income range, closely matches U.S. school population Other: parent education by less than bachelor’s degree, bachelor’s degree, and graduate degree. Disability categories: no disability, learning disability, speech-language disorder, mental retardation, and other handicap. Percentages close to U.S. school population data are presented. Comment: Elsewhere, perhaps in the TNL, I read that the percentage of the population with speech-language disorders was estimated to be 7%. Summary Prepared By: Eleanor Stewart 27 July 2007 Test Description/Overview: The manual provides a comprehensive introduction to phonological skills, theory, and description of subtests. Throughout, the information provided is clear and detailed in all areas (i.e., background, instructions for use, directions for administration, 1 Hayward, Stewart, Phillips, Norris, & Lovell explanation of scores, and standardization). The test kit consists of an examiner’s manual, a hard cover, coil bound test picture book, record booklets, and a CD contained in a sturdy cardboard box. The record booklet consists of identifying information, record of scores, profile of scores, and record of item and test performance by subtest. Each subtest is introduced in the booklet with brief, well labeled information about the material needed, ceiling rule, feedback allowed, scoring, and direction for practice and test items. The examiner’s text for test administration is printed in blue. Materials required for subtests include: a stopwatch, CTOPP CD with test items for Blending Words, Memory for Digits, Nonword Repetition, and Blending of Nonwords, and a CD player. Theory: The framework presented consists of three kinds of phonological processing important to the development of written language: phonological awareness, phonological memory, and rapid naming. Each is described as distinct but interrelated. The authors state, “Phonological awareness, phonological memory, and rapid naming represent three correlated yet distinct kinds of phonological processing abilities. These abilities are correlated rather than independent, in that confirmatory factor analytic studies reveal that the correlations between them are substantially greater than zero. They are distinct rather than undifferentiated, in that the correlations between them are less than one. In general, phonological awareness and phonological memory tend to be more highly correlated with one another than with rapid naming. In addition, the three kinds of phonological processing abilities tend to become less correlated with development. For very young children, phonological awareness and phonological memory can be nearly perfectly correlated” (Wagner, Torgeson, & Rashotte, 1999, pp. 6-7). A schema is presented in Figure 1.1 (paper copy of Chapter 1 on file). The subtests are constructed on the basis of the research tasks used to explore phonological skills. Purpose of Test: The purpose of this test is to assess phonological skills, to identify those students who are performing below their peers, to profile strengths and weaknesses for intervention, to document progress, and to use CTOPP as a tool in research. Areas Tested: Subtests are: 1. Elision* 2. Blending Words* 3. Sound Matching* 4. Memory for Digits* 2 Hayward, Stewart, Phillips, Norris, & Lovell 5. Nonword Repetition* 6. Rapid Color Naming* 7. Rapid Object Naming* 8. Rapid Letter Naming 9. Phoneme Reversal 10. Blending Nonwords 11. Segmenting Words 12. Segmenting Nonwords *Core Subtests for ages 5 and 6 years. Supplemental subtest at this age: Blending Nonwords. Comment: I learned a great deal from reading this section of the manual and would encourage clinicians to do the same. Areas Tested: Phonological Awareness Segmenting Blending Elision Other -see list above Who can Administer: Authors state that examiners should have extensive training in testing as well as a thorough understanding of test statistics. Comment: I also think that the examiner should be very familiar with phonology especially if you want to consider error data, which I do. Clinically, errors are of interest to me. Administration Time: The authors state test time is approximately 30 minutes. Comment: I think that more time is likely. The authors state that during rapid naming and phoneme reversal subtests, the examiner should encourage the student to respond within 2 seconds (on rapid naming) and 10 seconds (phoneme reversal). If no response during these specified times, the item is marked as incorrect. Test Administration (General and Subtests): Chapter 2 addresses, “Information to Consider Before Testing”. Eligibility, examiner qualifications, testing time, and procedures are briefly discussed. The authors note that many students will not have had experience with the type of tasks included in the CTOPP. They offer test practice items with examiner feedback. The student must complete at least one of the trial items in order to proceed with testing. Otherwise, testing should be discontinued. 3 Hayward, Stewart, Phillips, Norris, & Lovell Procedures include: practice items, feedback on practice items, prompting for timed subtests, discontinue rules, and instructions specific to each form (subtests to be given for that age range). Entry points and ceilings are uniform with all subtests beginning with the first item, and all but the Sound Matching and rapid naming subtests have ceilings of three consecutive failed items. These exceptions are noted in the manual and on the record form. Six examples of proper ceiling use are provided. A section on “Situational and Subject Error” outlines the sources of error variance including environment (e.g., uncomfortable setting) and examinee characteristics (e.g., fatigue, attitude). The authors encourage examiners to consider testing situation characteristics in the analysis of results. Other sections in this chapter include “Other Information About Testing”, and “Sharing the Test Results”. This is a good review of familiar material. Chapter 3 provides “Administration and Scoring of the CTOPP” for each subtest with age ranges identified. This chapter offers specific instructions for administering and scoring each subtest. Scripted examiner instructions to the student appear in red type. These are the same instructions that appear in blue in the test booklet. Though the instructions in the manual describe using an audiocassette recorder and cassette of stimulus items, the version of CTOPP currently available uses a CD as previously described. Test Interpretation: Chapter 4, “Interpreting the CTOPP” is dedicated to information on recording, analyzing, and using CTOPP scores as well as interpreting test scores and composites and conducting discrepancy analyses. The authors first show how to complete the profile booklet, including how to calculate exact age for the student examinee. Several examples of age calculation are provided. Sections II and III, “Record of Scores” and “Profile of Scores”, provide instructions with a demonstration with a student’s record. In the next section, “Test Scores and Their Interpretation”, each of the derived scores is defined and explained briefly. Regarding age and grade equivalent scores, the authors state that these scores have “come under close scrutiny in recent years so much so that the American Psychological Association (1985), among others, has advocated the discontinuance of these scores. In fact, the organization has gone so far as to encourage test publishers to stop reporting test scores as age and grade equivalents. Nevertheless, age and grade equivalents are currently mandated by many educational agencies and school systems. Because these scores are often required for administrative purposes, we provide them (reluctantly)” (Wagner, et al., 1999, p. 42). 4 Hayward, Stewart, Phillips, Norris, & Lovell Comment: This is the second or third manual in which the authors have made a statement such as this. I understand their reservations but I wonder what the rationale/defense is from the school’s point of view. I have found that clinicians are often “forced” to report these scores. Do these scores somehow align with other scores used? With respect to percentiles, the authors note that these scores are often the ones used by clinicians to explain results. They point out that “the distance between two percentile ranks becomes much greater as those ranks are more distant from the mean or average (i.e., the 50th percentile)” (Wagner, et al., 1999, p. 42). They state, “Standard scores provide the clearest indication of an examinee’s subtest performance…Standard scores allow examiners to make comparisons across subtests” (p. 44). The next sections cover discussions, with examples, of interpreting composite and individual subtest scores, discrepancy analyses (by calculating a difference score using standard scores to determine statistical significance for the difference), and clinical usefulness (in terms of severe discrepancies in difference scores). The last section in this chapter addresses “Cautions in Interpreting Test Results” with brief review of test reliability, using tests alone to diagnose, and limitations of test in terms of intervention planning. Regarding test reliability, the authors state, “Results based on tests having reliabilities of less than .80 should be viewed skeptically” (Wagner, et al., 1999, p. 56). Standardization: Age equivalent scores Grade equivalent scores Percentiles Standard scores Other (Please Specify) Composite Scores are determined from the sums of standard scores. Reliability Stanines The entire norming sample was used. Extensive description of reliability calculations is given and standard errors of measurement are provided. Impressive results are reported across subtests and composites (ie. nothing below .70 on any reliability calculation). The authors state,” The magnitude of these coefficients strongly suggest that the CTOPP possesses little test error and that users can have confidence in the results” (Wagner, et al., 1999, p. 73). Internal consistency of items: Except for the rapid naming subtests which used alternate-form reliability (appropriate for “speeded tests”), all subtests were investigated using Cronbach’s coefficient alpha. Composite scoreswere investigated for internal consistency using Guilford’s formula (again excepting rapid naming subtests as noted). Associated SEMs for standard scores and composites were presented (1s and 2s for subtests and 4s, 5s, and 6s for composites). Results: “100% of the alphas for the CTOPP subtests reach .70; 76% attain .80…and 19% attain .90, the optimal level” (Wagner, et 5 Hayward, Stewart, Phillips, Norris, & Lovell al., 1999, p. 68). Test-retest: The Tallahassee study involved 91 participants in three age ranges (n=32 ages 5 through 7 years, n=30 ages 8 through 17 years, and n=29 ages 18 through 24 years) after a two-week interval. Correlation coefficients ranged between .68 and .97 for the 5 to 7 year range, .72 to .93 for 8 to 17, and .67 to .90 for 18 to 24 years. Comment from the Buros reviewer: “Although the correlation coefficients are adequate, it is surprising that they are not stronger, particularly at the oldest age levels where one would believe that little development in phonological processing would occur between times of administration” (Hurford & Wright, 2003, p. 227). Inter-rater: Two staff members at PRO-ED independently scored 30 protocols from 5 and 6 years olds and 30 protocols from 7-24 year olds. Results were reported to be .98. Comment from Buros reviewer: “Although this method assesses the likelihood of arriving at similar results when the protocols have already been completed, it does not directly assess interrater reliability. To adequately assess this type of reliability requires that two individuals independently administer the CTOPP to the same child, transcribe the responses that the individual provides, and then score the protocol. Although the authors report in the manual that the interrater reliability was .98, this is an incomplete, inadequate, and invalid evaluation of interrater” (Hurford & Wright, 2003, p. 227). My comment: Isn’t this surprising, given the amount of resources that appear to have been dedicated to the development of this test? The upshot of this is that the reviewer concludes that the test has “acceptable psychometric properties”(Hurford & Wright, 2003, p. 229). Other: none Validity: Content: The authors provide an overview of the research on phonological skills in Chapter 1 “Rationale and Overview” and in Chapter 7 “Validity of Test Results” as well as discuss the tasks which were chosen based on those used in research studies to assess these skills. They also discuss the rationale for the format of the subtests and the selection of test items. Results of conventional item analysis and Item Response Theory (IRT) are reported. Differential item functioning analysis was performed (see section below). Criterion Prediction Validity: The results of several studies were reported. The CTOPP was compared with: 6 Hayward, Stewart, Phillips, Norris, & Lovell 1. Using a preliminary version of the test, CTOPP Composites were compared with the Word Identification and Word Analysis subtests of the Woodcock Reading Mastery Test-Revised (WRMT-R) on a sample of 216 children in kindergarten (53% girls, 26% minority students). Coefficients were found after one year in kindergarten: .71 for Phonological Awareness, .42 for Phonological Memory, and .66 for Rapid Naming and WRMT-R composites. The same group, assessed after Grade One, showed better values: .80, .52, and .70 respectively (note the modest correlations for Phonological Memory). 2. A revised version of CTOPP was used in the study of 603 public school students, approximately 100 per grade K-5 (69% Euro-American, 28% African American, 3% other minority groups) in Tallahassee, FL. The authors compared the Word Identification, and Word Attack of WRMT-R and the TOWRE Sight Word Efficiency and Phonetic Decoding Efficiency subtests. Partial correlations controlling for age between CTOPP subtests and criterion variables showed “moderate to strong correlations between CTOPP subtests and the criterion variables support [ing] the criterion-prediction validity of the test”. Results ranged from .25 to .74 (x=.48) (Wagner, et al., 1999, p. 92). 3. The final version of CTOPP was used in a study of 164 students, (approximately n=25 students in kindergarten and grades 2, 5, and 7, n=40 in high school and n=22 in college) in what appears to be a university affiliated school program in Florida. Demographic data were reported: 76% Euro-American, 20% African American, 4% minority. Using CTOPP and the WRMTR Word Identification subtest, results of partial correlations controlling for age between CTOPP subtests and the criterion variable of Word Identification were in moderate to high range (.46 to .66). 4. Students with learning disabilities (n=73) participated in a study in which the CTOPP was administered on two occasions with the Lindamood Auditory Conceptualization Test (LAC) administered on the first occasion. The WRMT-R Word Attack and Word Identification subtests and the Gray Oral Reading Tests 3rd edition Accuracy, Rate, and Comprehension subtests, and the WRAT-3rd ed were also administered, along with a spelling test. Intervention was initiated and carried out between the two test occasions. “Partial correlations controlling for age and corrected for unreliability between CTOPP subtests, the phonological awareness criterion variable, and the reading and spelling criterion variables…correlations were large for the CTOPP phonological awareness subtests (Elision and Blending Words) and rapid naming subtests (Rapid Digit Naming, Rapid Letter Naming), but variable for the memory subtests (i.e., Memory for Digits, Nonword Repetition)” (Wagner, et al., 1999, p. 94-95). 5. CTOPP was correlated with TOWRE in a study using the entire normative sample. Results indicated correlations “in the low to moderate range both for the kindergarteners and first graders, and for the second graders and older. The correlations are high enough to give support for the validity of CTOPP scores. The coefficients relative to the Phonological Awareness Quotient are particularly strong for the kindergarteners and first graders. The relationship between the CTOPP and TOWRE quotients is particularly encouraging in that it establishes the relationship between phonological processes and word reading 7 Hayward, Stewart, Phillips, Norris, & Lovell 8 fluency” (Wagner, et al., 1999, p. 96-97). Note: While CTOPP measures phonological abilities related to reading, the TOWRE measures reading ability. Construct Identification Validity: The confirmatory factor analysis performed confirms the construct validity of the CTOPP. “The model provided an excellent fit to the data…Comparative Fit Index (CFI) for the present model of .99 approached the maximum possible value of 1.00” (Wagner, et al., 1999, p. 98). Age differentiation: Coefficients were calculated and vary from low to high. The authors state, “These coefficients are high enough to demonstrate the developmental nature of the subtest’s contents. Because a relationship with age is a long-acknowledged characteristic of most phonological processing abilities, the data found…support the construct validity of the CTOPP” (p. 101). Group differentiation: Using mean standard scores for the entire normative sample and 8 identified subgroups, outcomes were as expected. Participants identified with speech/learning disabilities and language disabilities performed poorly. African American children scored slightly below average but the authors defend this outcome pointing to their earlier research that demonstrated that “performance on measures of phonological awareness is more modifiable by environment/language/training experience than is performance of measures of memory or rapid naming.” (p.103). Comment from the Buros reviewer: “One statement that the authors make regarding using group differentiation to support construct validity is somewhat inconsistent with their results from the differential item functioning analysis. The Delta scores indicated that there was no item bias for the CTOPP among African American vs. non-African American participants. However, there were differences between the standard scores of African American participants and other participants, some as large as a SEM from the mean. The authors claim that 'The differences among groups on measures of phonological awareness should not be taken as evidence of test bias, but rather as confirmation of the fact that differences in language experience in the home and neighborhood can have an impact on the development of phonological awareness in children' (manual, p. 103). Although this may be true, the evidence they use to support this claim is based on a study they performed that, most likely, included participants from the norming group. This renders the argument somewhat circular. As the authors note in the manual, the study of validity is a continuous process. This is one aspect of their validity study that warrants further investigation and verification” (Hurford & Wright, 2003, p. 228). Differential Item Functioning: Item bias was examined with male/female, European and non-European Americans, African Americans, other races, and Hispanic and other ethnic groups. Two methods were used: Logistical regression and Delta Scores. Using regression, with alpha at .01, the authors and their colleague at PRO-ED found 25 suspect items that were then eliminated from the final CTOPP. Using the second technique, correlation coefficients for Delta scores for the groups ranged between .86 and .99 Hayward, Stewart, Phillips, Norris, & Lovell 9 (x=.98). Therefore, differential item functioning was not evidenced. Other: none. Comment: I think they’ve exhausted themselves. Summary/Conclusions/Observations: Both Chapters 1 and 7 are valuable for clinicians wanting to have an overview of phonological skills, their theoretical basis, what processes are involved, how to assess, and implications. Given the implications of the student’s test performance in terms of academic achievement in reading, I think that clinicians need to be thoroughly knowledgeable about the information in this manual. The authors have done a very good job of describing why it is important to test phonological processing skills, how this is done, and how to interpret the findings. My guess is that the average clinician might need to be encouraged to read the entire manual but it is worthwhile to do so. Despite the reservations about reliability noted, overall the reviewers favour this test for its use of theory, task construction, and sound psychometric foundations. I concur. For the purpose of TELL development, I think that this test provides an excellent example of a thorough and detailed manual. However, I really had to concentrate to get through the evidence for validity. I finally had to sketch out the various studies in order to understand the range of studies conducted. Comment from the Buros reviewer: “One minor criticism of the manual concerns the authors' overly cautious remarks regarding interpretation of the results. This overly cautious attitude is present in several places within the manual. These remarks are most likely related to the authors' backgrounds in research. As researchers, the authors were trained to avoid statements that were not totally grounded in the data and to eschew making Type I errors (indicating there are differences, difficulties, or relationships that do not, in reality, exist). Given the massive amount of research examining the relationship between phonological processing and reading and language difficulties, the cautions are not warranted. Finally, the psychometric properties of the CTOPP are appropriate for making rather strong statements concerning one's phonological processing abilities” (Hurford & Wright, 2003, p. 229). Hayward, Stewart, Phillips, Norris, & Lovell Clinical/Diagnostic Usefulness: Yes, to this test. I would feel confident that I identified a student in need, and supported in reporting results as well as in planning intervention. References American Psychological Association (1985). Standards for educational and psychological tests. Washington, DC: Author. Hurford, D., & Wright, C. (2003). Test review of the Test of Word Reading Efficiency. In B.S. Plake, J.C. Impara, and R.A. Spies (Eds.), The fifteenth mental measurements yearbook (pp. 226-232). Lincoln, NE: Buros Institute of Mental Measurements. U.S. Bureau of the Census (1997). Statistical abstract of the United States (117th ed.). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce. Wagner, R., Torgeson, J., & Rashotte, C. (1999). Comprehensive test of phonological processing. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed. To cite this document: Hayward, D. V., Stewart, G. E., Phillips, L. M., Norris, S. P., & Lovell, M. A. (2008). Test review: Comprehensive test of phonological processing (CTOPP). Language, Phonological Awareness, and Reading Test Directory (pp. 1-10). Edmonton, AB: Canadian Centre for Research on Literacy. Retrieved [insert date] from http://www.uofaweb.ualberta.ca/elementaryed/ccrl.cfm 10