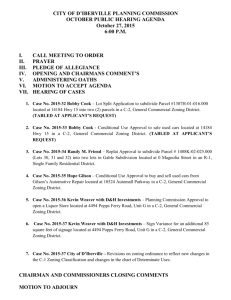

LAND USE - NYU School of Law

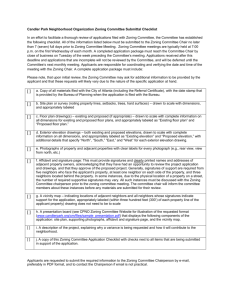

advertisement