Making War, Forging Revolution: Russia

advertisement

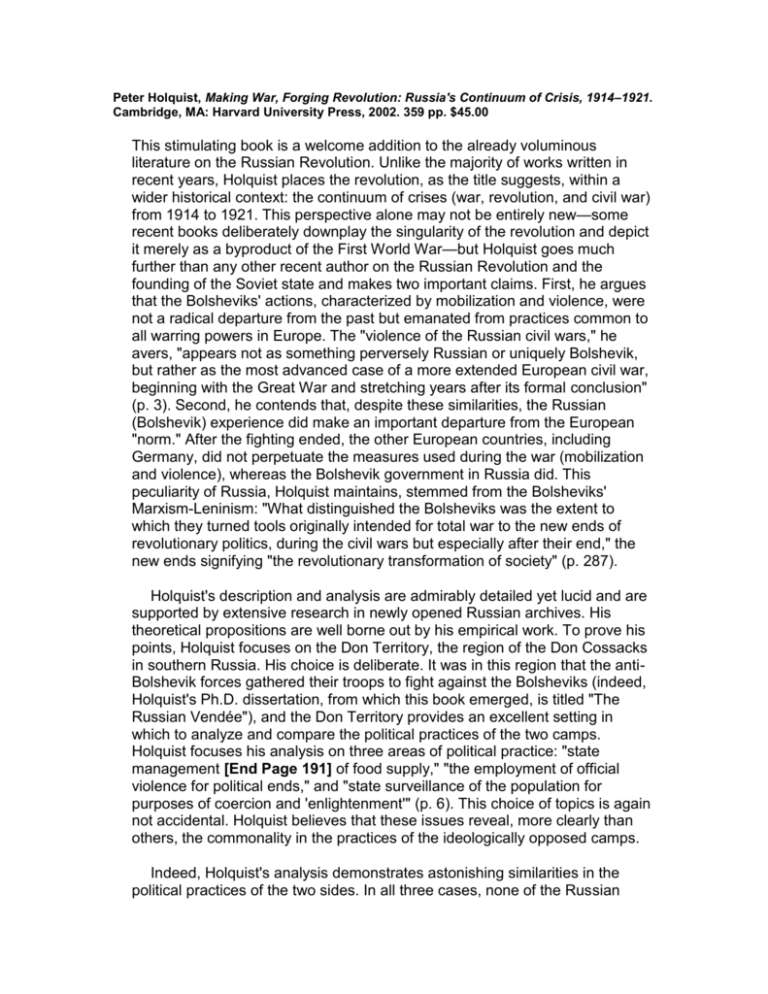

Peter Holquist, Making War, Forging Revolution: Russia's Continuum of Crisis, 1914–1921. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002. 359 pp. $45.00 This stimulating book is a welcome addition to the already voluminous literature on the Russian Revolution. Unlike the majority of works written in recent years, Holquist places the revolution, as the title suggests, within a wider historical context: the continuum of crises (war, revolution, and civil war) from 1914 to 1921. This perspective alone may not be entirely new—some recent books deliberately downplay the singularity of the revolution and depict it merely as a byproduct of the First World War—but Holquist goes much further than any other recent author on the Russian Revolution and the founding of the Soviet state and makes two important claims. First, he argues that the Bolsheviks' actions, characterized by mobilization and violence, were not a radical departure from the past but emanated from practices common to all warring powers in Europe. The "violence of the Russian civil wars," he avers, "appears not as something perversely Russian or uniquely Bolshevik, but rather as the most advanced case of a more extended European civil war, beginning with the Great War and stretching years after its formal conclusion" (p. 3). Second, he contends that, despite these similarities, the Russian (Bolshevik) experience did make an important departure from the European "norm." After the fighting ended, the other European countries, including Germany, did not perpetuate the measures used during the war (mobilization and violence), whereas the Bolshevik government in Russia did. This peculiarity of Russia, Holquist maintains, stemmed from the Bolsheviks' Marxism-Leninism: "What distinguished the Bolsheviks was the extent to which they turned tools originally intended for total war to the new ends of revolutionary politics, during the civil wars but especially after their end," the new ends signifying "the revolutionary transformation of society" (p. 287). Holquist's description and analysis are admirably detailed yet lucid and are supported by extensive research in newly opened Russian archives. His theoretical propositions are well borne out by his empirical work. To prove his points, Holquist focuses on the Don Territory, the region of the Don Cossacks in southern Russia. His choice is deliberate. It was in this region that the antiBolshevik forces gathered their troops to fight against the Bolsheviks (indeed, Holquist's Ph.D. dissertation, from which this book emerged, is titled "The Russian Vendée"), and the Don Territory provides an excellent setting in which to analyze and compare the political practices of the two camps. Holquist focuses his analysis on three areas of political practice: "state management [End Page 191] of food supply," "the employment of official violence for political ends," and "state surveillance of the population for purposes of coercion and 'enlightenment'" (p. 6). This choice of topics is again not accidental. Holquist believes that these issues reveal, more clearly than others, the commonality in the practices of the ideologically opposed camps. Indeed, Holquist's analysis demonstrates astonishing similarities in the political practices of the two sides. In all three cases, none of the Russian (whether Red or White) practices was in fact peculiar to Russia. Every warring power in Europe resorted to similar measures to fight a total war. Even within Russia, the Reds and the Whites used state power and violence in strikingly similar ways. Nevertheless, Russia's case was peculiar. Because Russia, unlike West European countries, lacked a true civil society, it fostered peculiar political attitudes (irrespective of ideological stances) that strongly favored the transformational power of the state. Both the Reds and the Whites considered the state an instrument not only for transforming society but also for establishing order. Alluding to the observation of the famous Russian scientist Vladimir Vernadskii (an influential member of the liberal Kadet party who nonetheless stayed in Soviet Russia and continued his scientific work for the Soviet state he detested), Holquist describes these attitudes as characterized by an aspiration to impose a "political organization of society" on a chaotic "democracy" (pp. 40, 110, 285). Holquist is careful, however, not to overstate the sameness of the Reds and the Whites. Bolshevik violence was much more open-ended than White violence. The Bolsheviks perpetuated mobilization and violence for the sake of transforming Soviet society according to their image of a socialist society. Their utopian ideology, Marxism-Leninism, distinguished them from all others. The reader will find much food for thought in this book. Holquist's emphasis on ideology is a welcome corrective to the recent emphasis on social and cultural factors. Yet one wonders whether the book is too deterministic. As in the pre–social history era, Holquist runs the danger of reifying ideology, elevating it to an all-encompassing concept that ultimately explains everything. To be sure, Holquist is aware of this danger and carefully studies practices as well. Still, it is telling that his narrative ends rather abruptly in 1921 when mass violence began to subside (if only temporarily). Even though he stresses that the Bolsheviks' use of mobilization and violence rose to new highs "especially after their [civil wars'] end," the complex history of the following decades may not be explained so neatly. Holquist states that Bolshevik violence was "invested with a redemptive and purifying significance" (p. 287), which may explain the scope and the depth it would later take (e.g., in dekulakization and collectivization), but the violence was often as mundane and prosaic as political violence used in other countries. Surely, the political leaders used this kind of rhetoric to glorify violence and the policies of the time. Holquist's emphasis on the rhetoric of violence runs the risk of downplaying its mundane origins and practices (e.g., the power struggle) and overinterpreting Soviet terror, thereby re-creating a history sui generis. These caveats aside, Holquist's book presents a large framework for interpreting the Russian Revolution and Soviet history and should be read by anyone interested in the subject. Hiroaki Kuromiya Indiana University