Ovarian Neoplasia in a Russian Hamster

OV ARIOHYSTERECTOMY IN A CAMPBELL’S RUSSIAN DWARF

HAMSTER WITH OVARIAN NEOPLASIA

E

LISABETTA

M

ANCINELLI

, DVM, MRCVS, C

ERT

Z

OO

M

ED

ECZM R

ESIDENT IN SMALL COMPANION EXOTIC MAMMAL MEDICINE AND SURGERY

Great Western Exotic Vets

Unit 10 Berkshire House, County Park,

Shrivenham Road, Swindon, SN1 2NR www.gwexotics.com

INTRODUCTION

Hamsters are one of the most popular small exotic mammals, having being kept as pets in

Britain since 1945. They are rodents belonging to the family Cricetidae with accounts for over 20 species of hamsters classified in seven genera. The most common species is the

Syrian or golden hamster ( Mesocricetus auratus ) but the Russian, Chinese and

Roborovski hamster are also commonly kept as pets in captivity [21].

The two species of hamsters belonging to the genus Phodopus are the Campbell’s Dwarf

Hamster ( P. campbelli ) and the Winter White Russian Dwarf Hamster ( P. sungorus ). They are the only two species than can interbreed and are very easily mistaken because of the similar colouration. The first one is the more common of the two species of Dwarf Russian

Hamsters kept as a pet.

CLINICAL CASE

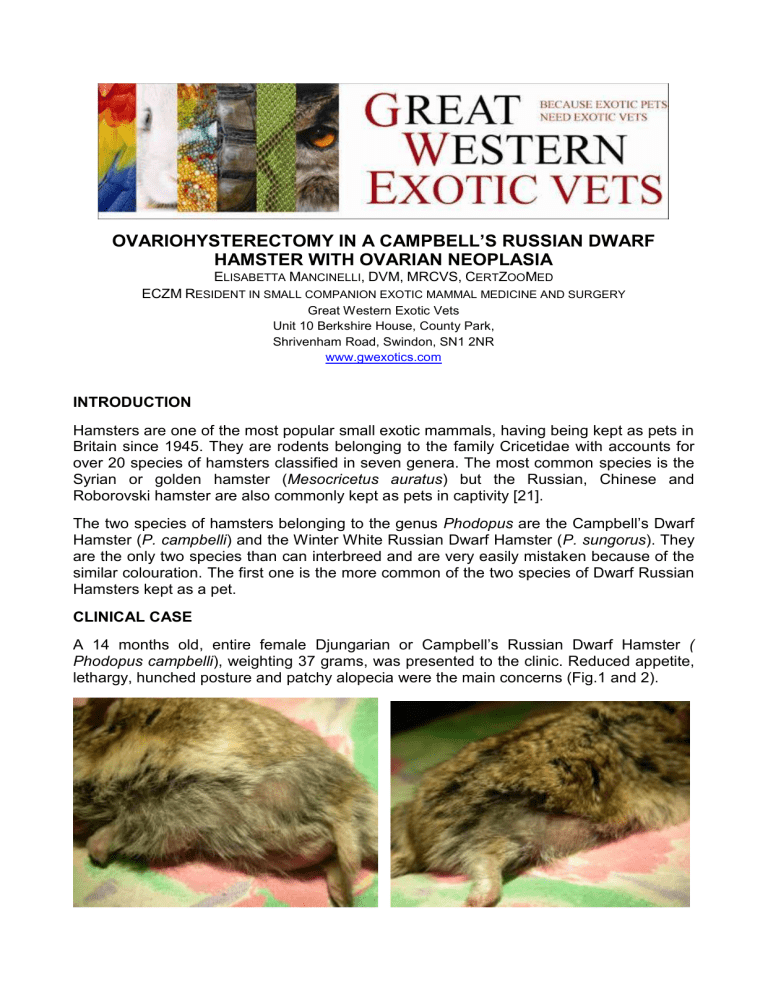

A 14 months old, entire female Djungarian or

Campbell’s Russian Dwarf Hamster

(

Phodopus campbelli ), weighting 37 grams, was presented to the clinic. Reduced appetite, lethargy, hunched posture and patchy alopecia were the main concerns (Fig.1 and 2).

Fig.1 and 2 Patchy alopecia was one of the concern reported by the owner.

The owner also reported an intermittent white vaginal discharge. On physical examination the hamster was thin, with a BCS of 2/5 and mildly dehydrated. The coat was staring but no skin abnormalities were evident. A firm structure could be palpated in the mid-cranial abdomen. The discharge was not evident at that time.

Financial constraints limited the diagnostic work up so no radiographs or ultrasonography could be performed and exploratory laparotomy was offered to the owner to confirm the presence of a suspected abdominal mass and attempt to surgically remove it.

SURGICAL PROCEDURE

4ml of warmed Hartmann’s solution (Aqupharm n°11, Animalcare, York, UK) were immediately given via subcutaneous injection in the scruff area and nutritional support was commenced with Oxbow critical care (Critical Care for Herbivores, Petlife Int, Bury St.

Edmund, UK). Buprenorphine (Vetergesic, 0.3mg/ml; Alstoe Animal Health, UK) and meloxicam (Metacam, 5mg/ml injectable solution; Boehringer Ingelheim) were given subcutaneously at 0.03mg/kg sc and 0.2mg/kg to provide peri-operative analgesia [6].

Enrofloxacin was started at 10mg/kg given initially via subcutaneous injection and then continued orally twice daily in the post-operative period [6].

A small gas chamber was used to induced anaesthesia. Isofluorane (Isoba 250ml,

Schering-Plough, Hertfordshire, UK) was delivered at an initial rate of 5% in 2L/min oxygen flow. Following induction, considering the small size of the patient, a syringe-case was attached directly to the Ayre T-piece anaesthetic circuit and used as a facemask.

Anaesthesia was maintained with Isofluorane 2.5% in 1L/min oxygen flow.

The abdomen was clipped, prepared for aseptic surgery and draped appropriately (Fig.3-

4).

Fig. 3 and 4 Preparation for the surgical procedure is showed.

A Doppler probe was positioned over the chest to monitor cardiac activity and hold in place by adhesive tape. The hamster was placed in dorsal recumbency on an electric heat pad to avoid hypothermia. A digital thermometer was used to check the temperature that was regularly maintained at 38°C during the procedure.

A midline incision was made immediately caudal to the umbilicus and the abdominal organs were exposed and identified. Iatrogenic damage to the intestinal structures was

carefully avoided while the caecum was gently retracted to visualise the uterine horns. The uterus was then grasped esteriorised and traced cranially to locate the ovaries normally located cranio-lateral to the kidneys (Fig. 4-5).

Fig. 4 and 5 The right uterine horn is grasped, exteriorised and followed to locate the corresponding ovary.

The mass felt during abdominal palpation corresponded to a right ovarian cyst (Fig.6).

Fig.6

The right ovarian cyst during celiotomy

An ovariohysterectomy was subsequently performed. A single artery and vein run medial to each ovary and along the uterus, following the uterine horns [20]. A single ligature was placed with a 5/0 absorbable synthetic suture material to ligate both ovarian pedicles

(Fig.7) and the structures were transected distally to the ligatures using an electrocautery

(ValleyLab TM. Surgistat II, electrosurgical generator, Southwest Medical LTD) (Fig.8).

Fig.7 and 8 The surgical procedure: an electrocautery was used for precise tissue cutting and appropriate coagulation in this case.

The procedure was performed on the controlateral side (Fig.9 -10).

Fig.9 and 10 The left ovary was ligated and resected in a similar manner.

Alternatively haemostatic clips can also be used. It is important to remove the entire oviduct as remnant can develop into cystic masses within the abdomen [10]. A transfixating ligature was placed at the level of the uterine cervix that was then transected distally (Fig.11).

Fig.11 A transfixating ligature is placed at the uterine cervix prior to distal resection.

A 5/0 monofilament absorbable suture was used for the linea alba and for subcutaneous and subcuticular continuous closure (Fig. 12).

Fig.12 Closure of the linea alba with absorbable suture material

The 1.5 cm diameter cyst, contained clear fluid and was firm on palpation (Fig.13). The uterine horns were grossly normal.

Fig.13

The gross appearance of the cystic right ovarian mass after surgical removal

Samples were collected in neutral buffered 10% formalin for histopathological examination.

POST-OPERATIVE PERIOD

After surgery the hamster was placed in an incubator at 32°C. Buprenorphine was administered at the same dosage every 6 hours whereas Meloxicam was continued orally every 24 hours. Antibiotic therapy was provided with oral Enrofloxacin at the same dosage.

Fluids were given subcutaneously during the recovery period to meet the maintenance requirements and correct the dehydration. Recovery from anaesthesia was uneventful.

Assisted feeding with oxbow critical care was commenced despite the hamster not being a true herbivore and continued until she started eating on her own the following day. The hamster was doing clinically well when recheck at 1 week. Unfortunately no long term follow-up is available.

Histopathological diagnosis was compatible with a granulosa cell tumour. A cyst containing pale, slightly turbid fluid was also attached anteriorly and it appeared to have arisen from the ovary. No concomitant uterine pathology was found.

DISCUSSION

According to part of the literature, hamsters have a low (3.7%) incidence of spontaneous tumours compared to mice and rats but they have the highest variety. This low incidence, along with the evidence that they are easily stimulated to produce tumours when exposed to carginogens, makes hamsters a very common species used in carcinogenesis research

[9].

Cystic ovarian disease has been commonly reported in pet rodents but occurs most often in hamsters and gerbils [25]. More commonly they are described in non-breeding females, they are bilateral and they can contain up to 2ml of fluid [21]. Neoplasia may also be involved. Unilateral granulosa cell or thecal cell tumors of the ovary are the most common reproductive system tumours reported although uterine adenocarcinoma is also considered common in chinese hamsters older than 100 weeks of age[14]. One author reports possible metastasis to the spleen, liver, lungs and peritoneum [12].

Other reproductive system tumours described include polyps, leiomyomas, leiomyosarcomas, cervical carcinomas and squamous papillomas of the vagina [9].

Common clinical sign include swollen abdomen, vaginal discharge or haemorrhage [17;

21]. Anorexia, lethargy, depression can be seen and there might also be compression and displacement of other abdominal organs if the mass/cyst reaches considerable dimensions

[9].

It is worthwhile to remember that female hamsters have a 4-days oestrus cycle and they usually exhibit a characteristic copious vaginal discharge postovulation (day 2 of the oestrus cycle). This discharge is creamy white and has a distinctive odor and it does not have to be mistaken and believed to be abnormal [7; 11]. A large amount of mucoid material and many bacteria on and around anucleated epithelial cells are its main cytological characteristics.

The lack of neutrophils and red blood cells also helps in distinguishing the normal oestrus discharge from a pathological one [4], as in the case reported.

Ovariectomy or ovariohysterectomy is the treatment of choice. Percutaneous drainage is reported as a palliative treatment [21] and paracentesis of as much fluid as possible from

the cyst before anaesthesia is recommended to improve the patient’s ventilation [1]. In hamsters with uterine adenocarcinoma it is contraindicated to drain the fluid from the lesion as this can result in metastasis. Uterine adenocarcinoma is considered fairly common in Syrian and Chinese hamsters and it has been shown to spread by seeding of malignant cells [24]. Ultrasonography in this case could have helped in determining whether the swelling was due to an ovarian cyst or uterine neoplasia.

Diagnosing neoplasia is similar in exotics as it is for dogs and cats. Routine haematology testing is not performed in pet hamsters due to the difficulty in obtaining a blood sample

[3]. Radiography and ultrasonography, along with other more complicated imaging modalities, are all useful in exotic oncologic cases to assess the extent of the tumour and eventually stage it [8]. Unfortunately none of these could be performed in the present case.

Aspirates and biopsies, where and when possible, should be submitted to increase the change of having a correct diagnosis and to provide a prognosis.

The prognosis is usually related to the hamster’s age and condition as well as the characteristics of the tumour removed and its adhesions with surrounding tissues [5].

Knowledge regarding the optimal treatment for tumours in exotic species is not extensive.

Surgical removal is frequently considered better than any other form of treatment in cases of localized cancer. Most of the surgical techniques in small mammals are analogous to those performed in dog and cats but with the challenge of the smaller size of our patients

[16]. In the present case ovariohysterectomy was performed to completely remove the mass, alleviate the pain and discomfort associated with it and increase the quality of life.

A synthetic absorbable suture material was used for routine ligatures but electrocautery was extremely useful for precise cutting of tissues and coagulating blood vessels as it is necessary in these type of surgery [16].

Rodents are physiologically unable to vomit so prolonged fast is not necessary. They are extremely prone to complications such as hypothermia (due to their large body surface area/volume ratio), hypovolemia from blood loss (relatively small amount of haemorrhage can be dangerous to small mammals), renal and respiratory compromise (small thoracic cavity, difficulty in intubation) [2]. Being prey species they are also extremely sensitive to stress. Therefore every effort should be made to minimize pain, fear and stress during the hospitalization period [2; 22].

Animals should be encouraged to eat as soon as possible after recovery and it is important that good pre and post-operative analgesia is provided to small rodents because pain can cause inappetence and prolong the effects of surgery [22]. Nutritional support it is a vital component of treatment for exotic patients with cancer and sick rodents will usually accept syringe feeding very well [13]. A timothy hay based critical care feeding formula (Oxbow

Critical Care, Oxbow Pet Products, Murdock, Nebraska) was used in this case, despite hamsters being omnivores animals and not strict herbivores, as previously used by the author to provide a high fiber diet in this type of rodents without any complication. The high fiber mixture was then supplemented with homogenized baby food and a rodent seed-mix, fresh vegetables and some fruit were added when the hamster started eating voluntarily.

Pain management is recommended for all patients that are critically ill. Mild to moderate pain can be alleviated with Nsaids but opioids might be needed for more severe pain.

Opioids such as butorphanol or buprenorphine are frequently used in exotic animals.

Nsaids have an opiod-sparing effect so when an opiod is to be added, lower doses can be used [8].

Alopecia or rough coats are nonspecific symptoms associated with many diseases and husbandry factors. Rough hair coat can be associated with fighting, soiled or wet bedding, and a variety of age-related diseases [7].

Granulosa cell tumours, arising from the specialized gonadal stroma of the ovary, are often reported to have the potential to secrete steroid hormones in different species such as horses, dogs, humans and ferrets [15; 26; 27; 9; 18]. Endocrine alopecia, as reported in dogs, ferrets, guinea pigs and gerbils [19; 18; 9; 23] might also be suspected in the present case.

REFERENCES

[1] Avery Bennet R. Rodents: soft tissue surgery. In BSAVA Manual of Rodents and

Ferrets. Edited by Keeble E and Meredith A; 2009.

[2] Avery Bennet R, Mullen HS. Soft tissue surgery. In: Quesenberry KE, Carpenter JW:

Ferrets, Rabbits and Rodents: Clinical Medicine and Surgery. Saunders (USA), 2 nd edition; 2004.

[3] Capello V. What every veterinarian needs to know about hamsters. EXOTIC DVM 2.5 pp. 38-41; 2000.

[4] Capello V. Pet hamsters: selected anatomy and physiology. EXOTIC DVM 3.2, pp. 23-

27; 2001.

[5] Capello V. Surgical techniques in pet hamsters. EXOTIC DVM 5.3 (ICE proceedings), pp.32-37; 2003.

[6] Carpenter JW. Exotic animal formulary. Third edition, Elsevier Saunders; 2005.

[7] Donnelly TM. Disease problems of small rodents. In Quesenberry KE, Carpenter JW:

Ferrets, Rabbits and Rodents: Clinical Medicine and Surgery. Saunders (USA), 2 nd edition; 2004.

[8]

Graham JE, Kent MS, Théon A. Current therapies in exotic animal oncology. In: Clin

North Am Exotic An Practice , 7: 757-781; 2004.

[9] Greenacre CB. Spontaneous tumours of small mammals. Vet Clin North Am Exotic An

Practice , 7: 627-651; 2004.

[10] Jenkins JR. Surgical sterilization in small mammals, spay and castration. Vet Clin

North Am Exotic An Practice, 3:617-645; 2000.

[11] Keeble E. Rodents: Biology and Husbandry. In BSAVA Manual of Rodents and

Ferrets. Edited by Keeble E and Meredith A; 2009.

[12] Lewis W. EXOTIC DVM vol.5.1, pp. 12-13; 2003.

[13] Lichtenberger M, Hawkins MG. Rodents: physical examination and emergency care.

In BSAVA Manual of Rodents and Ferrets. Edited by Keeble E and Meredith A; 2009.

[14] Lipman NS, Foltz C. Hamsters. In: Laber-Laird K, Swindle MM, Flecknell P, editors.

Handbook for Rodent and Rabbits medicine. New York, Pergamon, PP.65-82; 1995.

[15] Mair T, Love S, Schumacher J, Watson E. Equine medicine, surgery and reproduction. WB Saunders Company LTD; 1999.

[16] Mehler SJ, Avery Bennett R. Surgical oncology of exotic mammals. Vet Clin Exotic An

Practice, 7:783-805; 2004.

[17] Orr A. Rodents: neoplastic and endocrine disease. In BSAVA Manual of Rodents and

Ferrets. Edited by Keeble E and Meredith A; 2009.

[18] Patterson MM, Rogers AB, Schrenzel MD, Marini RP, Fox JG. Alopecia attributed to neoplastic ovarian tissue in two ferrets. Comparative Medicine, Vol.53, n 2; April 2003.

[19] Pluhar GE, Memon MA, Wheaton LG. Granulosa cell tumour in an ovariohysteroctomised dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc, Oct 15, 207 (8): 1063-5; 1995.

[20] Popesko P, Rajtova V, Horak J. A Colour Atlas of Anatomy of Small Laboratory

Animals. Vol.2: Rat, Mouse, Hamster. Wolfe, London; 1992.

[21] Richardson VCG. Diseases of small domestic rodents. Blackwell publishing, 2 nd edition; 2003.

[22] Richardson C, Flecknell P. Rodents: Anaesthesia and Analgesia. In BSAVA Manual of

Rodents and Ferrets. Edited by Keeble E and Meredith A; 2009.

[23] Rowe SE, Simmons JL, Ringler DH, Lay DM. Spontaneous neoplasms in aging gerbillinae. Vet Path 11: 38-51; 1974.

[24] Strandberg JD. Neoplastic diseases. In: Laboratory Hmasters, ed. GL Van Hoosier,

JR and CW Mcpherson, pp.157-168. Academic press, New York; 1987.

[25] Toft JD. Commonly observed spontaneous neoplasms in rabbits, rats, guinea pig, hamster and gerbils. Seminars in Avian and Exotic Pet Medicine 1, 80-92; 1991.

[26] Withrow SJ, MacEwan EG. Small Animal Clinical Oncology. Thrid edition, Saunders,

Philadelphia; 2001.

[27] Zydon C, Bogaars HA, Tucci JR. Virilizing granulose cell tumour responsive to human chorionic gonadotropin and oral contraceptive with 8-year follow-up. International journal of ginecology and obstetrics, Vol. 29, Issue 1, pp.87-90< 1989.