Doctoral Education in the UK

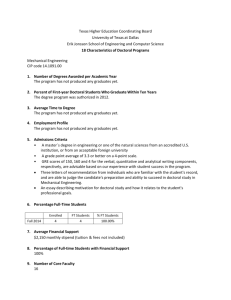

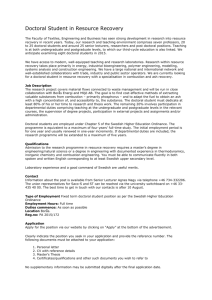

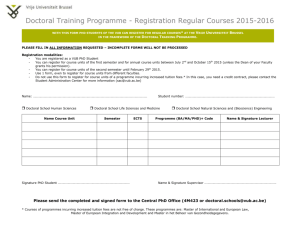

advertisement