A View of the Occupational Culture of Police

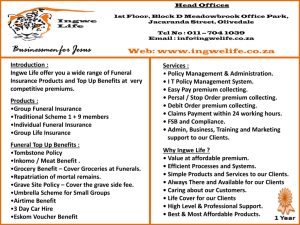

advertisement