Eric`s Concluding Reflections

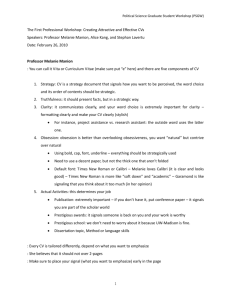

advertisement