Introduction to Bioethics

advertisement

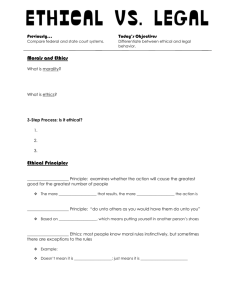

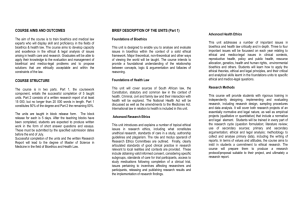

Introduction to Bioethics Since the middle of the 20th century, rapid improvements in technology have changed the practice of medicine. Technology allows physicians to restore or supplant basic body functions though organ transplants, mechanical devices like dialysis, ventilators, heart pacemakers, artificial nutrition and hydration, and exotic drugs. Initially, many of these technologies were viewed as positive, but many difficult problems have emerged in their implementation. There are difficult questions which have emerged- should we keep someone alive on life support or with artificial hydration just because we can? Who should decide? Patient Physician Family Nurse Social Worker Hospital administrator Insurance company Ethicist Politician Since the 1960s, the field of bioethics or biomedical ethics has emerged to consider these important topics. Major hospitals have ethics committees to assist patients and health care providers when they need help. Paralleling these medical advances have been breakthroughs in our knowledge of genetics and molecular biology. Genetic knowledge of specific diseases has increased and we are now able to identify persons who are carrying genes for such diseases. How do we decide what is right or wrong, what is better or worse, as medical biotechnology offers us more choices? Should everyone be screened for a genetic disease? Should genetically engineered products like human growth hormone or erythropoietin be available to everyone, or should we limit them to specific individuals with serious medical needs. Who should have access to your DNA data? Could genetic profiles be used to deny people employment or insurance? The Bioethics Decision-Making Model In attempting to answer difficult ethical questions, it is helpful to focus on a specific case and follow a step by step procedure. You will be presented with a specific case study from the New York Times to analyze and a decision making model to use. Part of the decision making will be to gather additional background facts to evaluate the situation and to find out what sort of ethical standards apply to the case. Finally you will make a decision as to the best course of action and justify it in terms of basic ethical principles. Identifying a dilemma A bioethics dilemma exists when there is no “right” course of action in a certain situation but, instead, several options, none of which is wholly acceptable. Ethical dilemmas revolve around trying to find the best solutions when no solution is completely good. Not every situation presents a dilemma; many times the possible causes of action are clearly right or wrong. The following example may clarify what does and does not constitute a dilemma. Assume a woman patient is a candidate for a drug research study, and she is given the drug by her doctor without her permission. This would clearly be wrong. Now assume the woman is informed about the risks and benefits of taking the drug. She sees benefits and risks relative to each choice. Now there is a dilemma. Once a dilemma has been identified, the next step is to pose the dilemma in the form of a question about the specific case. For example, in the case of the drug, the question can be posed, “Should the patient agree to part of the study?” Other questions could be analyzed in a case like this could be looked at individually. Since these discussions are usually interesting and emotional, it is easy to get off track. The decision-making model presented here reduces that risk. Basic ethical principles To make ethical decisions, we must agree on some basic guidelines about what constitutes moral conduct. In the field of biomedical ethics, certain guidelines are well established. The moral-action guides or principles can be divided into four major principles and several secondary ones. These principles are listed below. The terms in parenthesis are those used in the bioethical literature. Major Ethical Principles 1. Do no harm (nonmaleficence). 2. Do good (beneficence) 3. Do not violate individual freedom. (autonomy) 4. Be fair. (justice) Secondary Ethical Principles 1. Tell the truth (truth telling) 2. Keep your promise (fidelity and promis keeping) 3. Respect confidences (confidentiality) 4. Use the principle of proportionality: risk-benefit ratio (how much harm can be justifiably risked to effect good). 5. Attempt to avoid undesirable exceptions, also known as the wedge principle, the slippery slope or the camel’s nose. Although these rules are simple, the represent fundamental values associated with respect for human dignity that most people agree to. These are the principles to which you should refer when making and justifying decisions. Basic steps of the decision-making model. Here is a summary of the steps in the decision-making model. Each step will be explained more fully. 1. Identify the question you want to address. Usually, for any given case, many questions could be considered. Chose the one you want to explore. 2. Identify the issue you are exploring (i.e. genetic screening, confidentiality, gene therapy, human research subjects.) Naming the issue will help in searching for relevant literature. 3. State the facts of the case. Be sure to avoid inferences or conclusions. 4. Think of as many decisions as you can and write them down. 5. Gather additional information as needed. 6. Pick the decision you want to support. 7. State the ethical principle that supports your decision (your claim). 8. Identify an authority that supports your claim. Quote the authority if possible. 9. Formulate a rebuttal. Under what circumstances would you abandon your claim? 10. How strongly do you believe your claim? What is your level of confidence the qualifier? 11. Use the case format supplied for reporting your case. 12. Write a prose argument describing the case and your decision. When discussing a bioethics case, use the following rules of etiquette in the classroom. 1. Only one person at a time speaks after being recognized by the discussion leader. 2. Treat each other with respect; no name calling. Critique the argument not the author of the argument. 3. Seek clarity by asking questions. 4. Look for gaps in the data. 5. Recognize your own biases. 6. Be true to your own position; do not jump on the bandwagon. 7. Keep emotions in check. Use logic. 8. Do not follow authority blindly (teacher does not know everything). 9. You must have a reason, not an opinion. You can like pepperoni pizza better than anchovy pizza with no reason. Bioethical issues cannot be decided just on opinion. 10. Be open-minded and willing to be perplexed. Read the New York Times article on Pre-implantation Genetic Diagnosis for embryo. A family is given the opportunity to select one embryo that does not have a gene which increases the risk of cancer for implantation. There are a lot of questions that could be explored on this topic.