- The University of Liverpool Repository

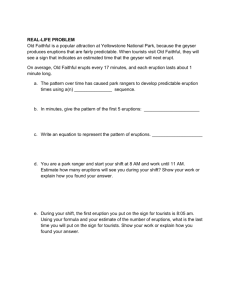

advertisement