Thoughts on what students need to learn at school

advertisement

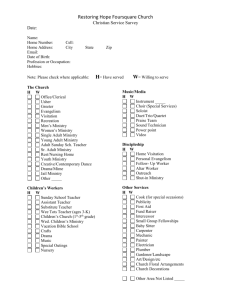

Thoughts on what students need to learn at school Summary for discussion purposes Paper prepared by Melissa Brewerton for the Ministry of Education October 2004 This is not a statement of government policy. The views expressed in this document are not necessarily those held by the Ministry of Education. Thoughts on what students need to learn at school: Summary for discussion purposes Accessed from http://www.tki.org.nz/r/nzcurriculum/references_e.php © Ministry of Education – copying restricted to use by New Zealand education sector Page 1 of 20 PURPOSE This paper sets out some thinking about the types of learning all students need, ideally by the time they finish their schooling. This paper is drawn from a research-based think-piece on the characteristics of a ‘successful’ school leaver1, and is intended to stimulate debate in relation to the Curriculum Project, the Secondary Futures Project, Schooling Strategy and other policy work related to the outcomes of schooling. INTRODUCTION In the era of the ‘knowledge society’ and ‘life-long learning’, schooling can be seen as one part of a life-long journey. However, the expectation that people will continue learning throughout life in further education and employment contexts can avoid the question of whether there are particular competencies 2 that all people should develop at school to enable them to continue successfully on their life journeys after leaving school. Curriculum review includes an analysis of what a nation wants its citizens to gain from school and the nature, characteristics and needs of society (Ministry of Education, 2003:10). There is general consensus internationally and among New Zealand (NZ) stakeholder groups that students need to leave school with the learning necessary for making decisions about, and participating in, further education, work and wider society. Students need this learning for participation in their current lives as well. However, there is a range of views about what this learning actually entails. When looking at what people need to learn for participation in life, we are not just looking at the nature of society (present or future) into which those individuals must fit, but also what those individuals can contribute towards shaping the nature of that society (O’Neill, 1997: 132). Rather than seeing schooling as a means of shaping young people to fit a particular desirable ‘mould’, schooling can be seen as providing a basis for people to make wellfounded decisions and to be informed and critical participants in a range of life contexts (Snook, 1996; and Himona, 2000). While some see this as highlighting the primary importance of key competencies, specific competencies are just as essential for effective participation in life. WHAT DO YOUNG PEOPLE NEED TO PARTICIPATE IN LIFE? What do stakeholders think? The New Zealand Curriculum (NZC) defines what young people should learn at school. The Curriculum Project is revising the national curriculum to refine and clarify the key learning needed by NZ students through essence 1 2 Paper prepared by Melissa Brewerton for the Ministry of Education in October 2004. See Definitions in Appendix 1 This is not a statement of government policy. The views expressed in this document are not necessarily those held by the Ministry of Education. Thoughts on what students need to learn at school: Summary for discussion purposes Accessed from http://www.tki.org.nz/r/nzcurriculum/references_e.php © Ministry of Education – copying restricted to use by New Zealand education sector Page 2 of 20 statements for each Essential Learning Area (ELA) integrated with a framework of key competencies and overarching principles. In general, all stakeholders (students, teachers, employers, parents, government) want students to leave school able to pursue a constructive lifepath, which, they generally suggest, requires a combination of: o Skills, primarily literacy, communication, teamwork, and numeracy o Attitudes/values, primarily self belief/esteem, confidence, motivation, reliability, and positive attitude to learning o Knowledge. The order of priority of these components varies according to stakeholder groups, but in general, attitudes, values and key competencies are seen as the most important. Work on the Schooling Strategy has suggested that this may be because knowledge is taken for granted and respondents want to emphasise the learning which they think does not have sufficient emphasis in the curriculum (i.e. skills and attitudes/values). To the extent that the purpose of education is to prepare people for participation in society, it needs to be remembered that preparation for participation in Māori society is also required (Durie, 2003). Māori have specific goals regarding te reo and tikanga Māori. What learning do young people need at school, then? The oft-cited ‘changing world’ argument suggests that since knowledge and specific skills can become outdated, schools should focus on developing more adaptable skills and knowledge as ‘process’ rather than content. Such views tend to undervalue knowledge by: o Ignoring the importance of knowledge in providing a shared ‘cultural literacy’ which enables members of a society to communicate and contribute to society o Assuming knowledge = ‘facts’ or ‘information’ rather than ‘understanding’ (which does not become outdated) o Ignoring the importance of knowledge as a basis for further learning (scaffolding) o Ignoring the importance of knowledge as content and context for skill development. In addition, subject disciplines and ELA cannot be dismissed as arbitrary bodies of knowledge, as they each provide a particular way of knowing, thinking, or doing, with their own concepts and methods (Hargreaves, 2004). Everyone also needs to have a basis of knowledge about the world or a shared ‘cultural literacy’ to enable them to participate meaningfully in society (Hirsh in Uchida, 2003). For example, everyone (ideally) needs some understanding of science and technology to be informed participants in the debates about genetic engineering. People also need a ‘complex and richly structured knowledge base’ to support the development of more complex cognitive and metacognitive competencies and expertise in some area(s) (e.g. Gillespie, 2002). This is not a statement of government policy. The views expressed in this document are not necessarily those held by the Ministry of Education. Thoughts on what students need to learn at school: Summary for discussion purposes Accessed from http://www.tki.org.nz/r/nzcurriculum/references_e.php © Ministry of Education – copying restricted to use by New Zealand education sector Page 3 of 20 The concept of ‘competencies’ overcomes, to a certain extent, the debates about skills versus knowledge by suggesting that skills, knowledge, attitudes and values are all integrated in performance (OECD, 2003). Competencies can apply to a wide range of life contexts (key competencies) or a limited number of contexts (specific competencies). People always use both key and specific competencies together. Despite the holistic and integrated nature of competencies, the focus on key competencies can lead to the undervaluation of specific competencies and associated ‘subjects’ or ELA. The proposed framework for the New Zealand Curriculum Framework (NZCF) has interconnected groups of key competencies with the learner, identity, well-being and belonging at the core. Identity, well-being and belonging are foundations for learning, as learning is most effective where what students know, who they are, where they come from, and how they know form the foundations of interaction in the classroom. This also recognises the importance of the environment in establishing the conditions for learning. The key competency groups are interconnected with specific competencies through the essential learning areas: Key competencies in the NZCF MEANINGFUL AND REAL-LIFE LEARNING CONTEXTS Thinking Managing self LEARNER ESSENTIAL LEARNING AREAS ESSENTIAL LEARNING AREAS Identity(ies) Well-being Belonging Relating and participating Making meaning (multiliteracies) This is not a statement of government policy. The views expressed in this document are not necessarily those held by the Ministry of Education. Thoughts on what students need to learn at school: Summary for discussion purposes Accessed from http://www.tki.org.nz/r/nzcurriculum/references_e.php © Ministry of Education – copying restricted to use by New Zealand education sector Page 4 of 20 The proposed framework of key competencies for the NZCF promotes a lifelong learning model through consistency with Te Whāriki, the proposed NZ tertiary education framework, and the international framework from the OECD. Life-long learning framework of key competency groups for NZ and internationally Contexts Te Whāriki Strands NZCF Key competency groups Tertiary Key competency groups Wellbeing Belonging OECD DeSeCo Key competency groups Managing self Acting autonomously Acting autonomously Learner in contexts Contribution Communication Exploration Learner Identity(ies) Well-being Belonging Learner Relating and participating Making meaning Thinking Individual Relating to others Using tools Interacting in groups Using tools Thinking (crosscutting) Critical thinking (cross-cutting) Contexts The importance of contexts for learning Contexts for learning are important both in relation to the content and application of learning, and engagement in the learning process (including pedagogy). All competencies are context dependent to a certain extent, not just specific competencies. Key competencies take different forms in different contexts, including different cultural contexts (e.g. Hager, 1997:13-14). For example, ‘relating to others’ will be quite different in a hierarchical context compared with an egalitarian context, or a competitive context compared with a cooperative context. The degree of adaptation of key competencies to new contexts depends on how different the context or demands are, and the level of expertise of the individual in both the key competency and associated specific competencies (e.g. Gillespie, 2002). Identity may be a key to transferring competencies to new contexts, or ‘the vehicle that carries our experiences from context to context’. For example, if This is not a statement of government policy. The views expressed in this document are not necessarily those held by the Ministry of Education. Thoughts on what students need to learn at school: Summary for discussion purposes Accessed from http://www.tki.org.nz/r/nzcurriculum/references_e.php © Ministry of Education – copying restricted to use by New Zealand education sector Page 5 of 20 you see yourself as a ‘creative’ person, then you are more likely to be able to be creative in new contexts (e.g. Carr, 2004). Learning related to meaningful, real-life contexts is important both to ensure the engagement of students and to provide opportunities to gain the learning needed for life3. Young people are keen to participate in, understand, and contribute to their world(s), and therefore engage with learning that has meaning for them (Russell, 2004). The curriculum project work with students has shown that they want to gain learning that is meaningful and useful to them now, as well as in the future. The use of meaningful, real-life (or authentic) contexts as a key means of teaching ‘the curriculum’ will enable young people to better understand how they learn, how life contexts offer opportunities to learn, and how to continue learning when ‘learning’ is not directly supported by a formal learning environment (Alton-Lee, 2003; and Hargreaves, 2004). What children learn from their classroom experiences is significantly affected by their prior knowledge. Learning is most effective where teachers use children’s culturally generated models of ‘sense-making’ and interact with children so that knowledge is ‘co-constructed’ (Bishop, 2003; and Alton-Lee and Nutthall, 1994). Learning communities in the classroom or school provide environments that facilitate learning if all are included in the ‘us’ and diversity is valued (Alton-Lee, 2003). Note that research and PISA findings indicate that ‘engagement with’ or ‘belonging in’ school is not the same as engagement in learning, and does not necessarily result in improved learning. 3 This is not a statement of government policy. The views expressed in this document are not necessarily those held by the Ministry of Education. Thoughts on what students need to learn at school: Summary for discussion purposes Accessed from http://www.tki.org.nz/r/nzcurriculum/references_e.php © Ministry of Education – copying restricted to use by New Zealand education sector Page 6 of 20 TEACHING AND LEARNING AS WEAVING Meaningful and real-life contexts Key competencies Thinking Making meaning Relating Participating & Contributing Learner Identity Belonging Wellbeing Managing self Pedagogy & class communities Specific competencies in ELA Knowledge base for future learning Subject disciplines as distinct ways of knowing, thinking and doing Knowledge as deep understanding Knowledge for shared ‘cultural literacy Contexts for key competencies WHAT IS THE SHAPE OF THE ‘PORTFOLIO’ OF LEARNING NEEDED BY YOUNG PEOPLE AT SCHOOL? Combining stakeholder views and research, a school leaver ideally needs to: Have a positive sense of identity(ies) Take responsibility for themselves, be motivated, reliable and confident Be able to understand and critique the nature of the world around them and make informed decisions, e.g. able to make well-founded decisions about their lives, can be an informed participant in public debates, can identify areas for own development Participate effectively in, and contribute to, a range of life contexts, including family, community, education and work Be able to engage in learning throughout life. The recent shift of the knowledge society towards learning for life, with education options centred around the individual, means that individuals need to actively make choices about their life pathways, including the education ‘portfolio’ needed to take them where they want to go. The availability of a wide range of learning opportunities through the NZC, National Qualifications This is not a statement of government policy. The views expressed in this document are not necessarily those held by the Ministry of Education. Thoughts on what students need to learn at school: Summary for discussion purposes Accessed from http://www.tki.org.nz/r/nzcurriculum/references_e.php © Ministry of Education – copying restricted to use by New Zealand education sector Page 7 of 20 Framework (NQF), including the National Certificate of Educational Achievement (NCEA), assumes that individuals (and their teachers, parents, whānau etc) have the skills and knowledge necessary to make effective and appropriate decisions. With such a plethora of choice, it can be hard for people to navigate their way through the options without some overall guidance about the shape of a portfolio of learning needed for a school leaver to be successful. The proposed Individual Career Plans, to be piloted in 2005 with year 10 as part of the Beginning Careers project, will assist with this4. There may be a need to articulate within the curriculum and qualifications systems a framework of key learning that will support effective choice and successful transitions into constructive life pathways for students. These key learning objectives could be met through a range of learning opportunities based on real-life and/or meaningful learning contexts. Learning at school therefore requires an integrated combination of: Support for, and learning about, identity(ies), belonging and wellbeing Key competencies: o Thinking o Relating and participating o Managing self o Making meaning using multi-literacies o Cross-cutting: attitudes and values Specific competencies: o Sufficient knowledge about the world to have a basis for further inquiry and thought for effective participation in life o Sufficient experience in subject disciplines to learn a range of ways of knowing, thinking or doing o Sufficient depth of knowledge in some area to enable deep understandings, insights and high levels of expertise in key competencies to be developed o Specific competencies that form the basis of further learning (including in a work context) beyond school Meaningful life contexts: experience and understanding of real-life contexts and an ability to relate learning to these contexts: o Work o Family/whānau o Culture/ Tikanga Māori o Leisure/sports o Wider society and world. 4 The Individual Career Plans, to be piloted in 2005, will directly address this issue by providing guidance for students in year 10 to develop career plans, including subject choices during school. This is not a statement of government policy. The views expressed in this document are not necessarily those held by the Ministry of Education. Thoughts on what students need to learn at school: Summary for discussion purposes Accessed from http://www.tki.org.nz/r/nzcurriculum/references_e.php © Ministry of Education – copying restricted to use by New Zealand education sector Page 8 of 20 The proposed new curriculum framework, integrating key competencies, essence statements about core learning in each ELA, and key principles will provide a powerful basis for a curriculum that provides opportunities to gain the key learning needed by all. However, the integrated nature of the framework and associated teaching and learning needs to be emphasised. The NZC and the qualifications system need to fit together to support common goals and understandings of the learning needed by students for their various life pathways. The NCEA sought to make the standards of achievement more explicit so students, teachers and others knew what was being taught and learnt, and to shift the focus of professional practice from assessment of learning to assessment for learning. While the close specification of standards enables people to better understand the detail of what has been learnt, it can also mean that students, teachers and others lose sight of the bigger picture, i.e. to what overall learning the standards are contributing. It can also mean ‘a little bit of everything’ but little or no depth. More explicit articulation of the overall key and specific competencies to which achievement and unit standards contribute would better enable students to understand what it is that they are learning, and how best to put together an education portfolio that provides them with the range and depth of learning they will need in order to be a ‘successful’ school leaver. This does not mean greater specification of discrete learning outcomes within achievement or unit standards, but rather a more holistic approach that links the standards to overarching competencies. CONCLUSION The review of the NZ curriculum offers an opportunity to reconsider what it is that we think young people need to learn at school. This does not just mean the wide range of learning offered by all the ELA, but also consideration of what elements of learning should underpin all learning for students. A framework of overarching key learning outcomes could include: Key learning integrating: o Key competencies of thinking, managing self, relating and contributing, and making meaning (multi-literacies) o Specific competencies (subject and/or sector related) covering learning needed for a shared ‘cultural literacy’ providing opportunities for learners to develop different ways of ‘knowing’, ‘thinking’ and ‘doing’ providing for depth and supporting interests Key learning supported by teaching and environments which: o support and build identity(ies), belonging and well-being o provide meaningful, real-life contexts related to interests, family, community, work etc. This is not a statement of government policy. The views expressed in this document are not necessarily those held by the Ministry of Education. Thoughts on what students need to learn at school: Summary for discussion purposes Accessed from http://www.tki.org.nz/r/nzcurriculum/references_e.php © Ministry of Education – copying restricted to use by New Zealand education sector Page 9 of 20 In addition, there is a need to support young people to increasingly make their own independent decisions through providing advice and guidance, and actively teaching decision-making competencies. Effective teaching is fundamental to effective learning, and without effective teaching, any curriculum change is unlikely to improve overall outcomes for students. Research indicates that effective learning: o begins in a classroom community with a student’s own knowledge, connected with their experience and sense of identity; o moves on through co-construction of new competencies with the teacher scaffolding the learning; and o must be meaningful to the learner, and therefore connected to their experiences and the ‘real world’. While this paper suggests a basic framework of learning that students ideally need to learn at school, this does not mean that someone has ‘failed’ if they do not gain this learning at school. A successful life-long learner is someone able to continue learning in other contexts. Such a person would need, above all, a positive sense of self as learner, and the key competencies related to ‘learning to learn’ such as resilience and making effective decisions involving judgement and other cognitive competencies. A school leaver able to continue learning is not a ‘failure’, and is, indeed, a successful life-long learner. This is not a statement of government policy. The views expressed in this document are not necessarily those held by the Ministry of Education. Thoughts on what students need to learn at school: Summary for discussion purposes Accessed from http://www.tki.org.nz/r/nzcurriculum/references_e.php © Ministry of Education – copying restricted to use by New Zealand education sector Page 10 of 20 Appendix 1 Definitions Competencies are conceptualised as the capabilities needed to ‘do something’:5 o Competencies include skills, knowledge, attitudes and values needed to meet the demands of a task o Competencies are performance based and manifested in actions (including internal thought processes) of an individual in a particular context Essential skills are those generic skills currently specified in the New Zealand Curriculum Framework Generic skills are used in this document where the text relates to existing or historic use of that term. It can generally be read as synonymous with key competencies, although it usually implies a narrower concept of skill without the associated knowledge, attitudes and values Key competencies are defined as those competencies needed by everyone across a variety of different life contexts to meet important demands and challenges, for example, relating well to others or literacies Knowledge is defined as what people know and understand (‘knowing how’ , ‘knowing that’ and ‘knowing why’) Performance is used to describe actively or intentionally doing things, including thinking School leaver is used to mean someone who leaves school not intending to return to schooling Schooling is used to mean formal learning opportunities provided while a person aged 5-18 is enrolled at a school, including learning ‘managed’ but not actively delivered by a school and home-schooling, but not including community education Skills are defined more narrowly as what people can do in relation to physical skills and cognitive strategies Specific competencies are defined as those competencies that are specific to a very limited number of contexts, for example, motor mechanics or playing the piano. 5 The OECD Defining and Selecting Key Competencies (DeSeCo) work uses the term ‘competence’ in the singular, whereas this document uses the term ‘competency’ to avoid confusion with the concept of ‘competence’ meaning being able to do something well (i.e. a level of achievement). This is not a statement of government policy. The views expressed in this document are not necessarily those held by the Ministry of Education. Thoughts on what students need to learn at school: Summary for discussion purposes Accessed from http://www.tki.org.nz/r/nzcurriculum/references_e.php © Ministry of Education – copying restricted to use by New Zealand education sector Page 11 of 20 REFERENCES Adolescent Health Research Group (2003) New Zealand Youth: A profile of their health and wellbeing. Auckland: University of Auckland. Alton-Lee, Adrienne and Nutthall, Graeme (1991) Understanding Teaching and Learning Project: Phase Two. Final Report to the Ministry of Education. Alton-Lee, Adrienne (2003) Quality Teaching for Diverse Students in Schooling: Best Evidence Synthesis. Wellington: Ministry of Education. Anae, Melani; Anderson, Helen; Benseman, John; and Coxon, Eve (2002) Pacific Peoples and Tertiary Education: Issues of Participation: Final Report. Auckland Uniservices Ltd for the Ministry of Education. Downloaded from http://www.minedu.govt.nz/web/downloadable/dl6828_v1/participation.doc Baker, Glenn (2003) ‘Situations Vacant’ in Special Report: Staff and Sales Training. Downloaded from www.nzbusinessmag.co.nz Bamford, Hazel (2000) ‘“Excellent Communication Skills Required”: Do the words in job advertisements tell us what communication abilities employers require?’ Communication Journal of New Zealand. 1(1). New Zealand: New Zealand Communications Association. Bassanini, Andrea and Scarpetta, Stefano (2001) Does human capital matter for growth in OECD countries? Evidence from pooled mean-group estimates. OECD Economics Department Working Papers 282, OECD Economics Department. Bishop, Russell and Glynn, Ted (1999) Culture Counts: Changing power relations in education. Palmerston North: Dunmore Press. Bishop, R; Berryman, M; Tiakiwai, S; and Richardson, C; (2003) Te Kōtahitanga: The Experiences of Year 9 and 10 Māori Students in Mainstream Classrooms: Report to the Ministry of Education. Wellington: Ministry of Education. Black, Paul (2000) Report to the Qualifications Development Group, Ministry of Education, New Zealand on the proposals for the development of the National Certificate of Educational Achievement. Unpublished paper held by the Ministry of Education. Boyd, Sally; Chalmers, Anna; and Kumekawa, Eugene (2000) Beyond School: Final year students’ experiences of the transition to tertiary study or employment. Wellington: NZCER. Cameron, Marie (2003) Ministry of Education Curriculum Stocktake in Values, Skills and Attitudes. Wellington: NZCER. This is not a statement of government policy. The views expressed in this document are not necessarily those held by the Ministry of Education. Thoughts on what students need to learn at school: Summary for discussion purposes Accessed from http://www.tki.org.nz/r/nzcurriculum/references_e.php © Ministry of Education – copying restricted to use by New Zealand education sector Page 12 of 20 Carr, Margaret (2004) Key Competencies/Skills and Attitudes: a Theoretical Framework: Background paper prepared for the Ministry of Education. April 2004. Unpublished paper held by the Ministry of Education. Carrodus, Andrea (2002) Key Attributes Employers Seek in Employees Retail Sector. Paper for Diploma in Career Counselling. Downloaded from http://www.cit.ac.nz/schools/counselling/studentwork/KeyAttributesEmplyersS eekInTheRetailSector.doc Chappell, C; Gonzi, A; and Hager, P (2000) Competency-based Education in Understanding Adult Education and Training. NSW: Allen and Unwin. Claxton, Guy (2003) ‘Building up young people’s learning power: Is it possible? Is it desirable? And can we do it?’. Educating for the 21st Century: Rethinking the Educational Outcomes we want for Young New Zealanders. NZCER Conference Proceedings. August 2003. NZCER: Wellington. Colmar Brunton Research (1997) New Zealand Employment Service - 1997 Employer Monitor. Wellington. Coxon, Eve; Anae, Melani; Mara, Diane; Wendt-Samu, Tanya; Finau, Christine (2002) Literature Review On Pacific Education Issues: Final Report 2002. Report prepared for the Ministry of Education by Auckland Uniservices Ltd, University of Auckland Crooks, Terry and Flockton, Lester (2002) Assessment Results for Māori Students 2001: Information Skills; Social Studies; Mathematics. National Education Monitoring Report 24. Wellington: Ministry of Education. Crooks, Terry and Flockton, Lester (2003) Assessment Results for Māori Students 2002: Writing; Listening and Viewing; Physical Education. National Education Monitoring Report 28. Wellington: Ministry of Education. Crooks, Terry and Flockton, Lester (2004) Assessment Results for Māori Students 2003: Science; Visual Arts; Graphs, Tables and Maps. National Education Monitoring Report 32. Wellington: Ministry of Education. David, Paul A (2001) Knowledge, Capabilities and Human Capital Formation in Economic Growth: A Research Report to the New Zealand Treasury. Treasury Working Paper. Oxford, April 2001. Dale, Roger and Robertson, Susan (1999) ‘Resiting’ the Nation, ‘Reshaping’ the State. Education Policy in NZ: the 1990s and beyond. Department of Labour (2004) Growth Through Innovation: Part II: Where to next? Unpublished paper. Department for Education and Skills (DES) (2004) Five Year Strategy for Children and Learners. Downloaded from http://www.dfes.gov.uk/publications/5yearstrategy/exec.shtml This is not a statement of government policy. The views expressed in this document are not necessarily those held by the Ministry of Education. Thoughts on what students need to learn at school: Summary for discussion purposes Accessed from http://www.tki.org.nz/r/nzcurriculum/references_e.php © Ministry of Education – copying restricted to use by New Zealand education sector Page 13 of 20 Durie, Mason (2003) Nga Kahui Pou Launching Māori Futures. Wellington : Huia. Durie et al. ( 2002 ) Māori Specific Outcomes and Indicators : a report prepared for Te Puni Kokiri , the Ministry of Maori Development. Palmerston North : School of Maori Studies, Massey University. Durie, M (2003) Māori Education Advancement. Conference Paper at Hui Taumata Mātauranga Tuatoru. Egan, Kieran (2001) ‘Why is Education so Difficult and Contentious?’. Teachers College Record (103: 6) December 2001: 923-941, Columbia University. Field, Laurie (2001) Industry Speaks: Skill requirements of leading Australian workplaces. Employability Skills for the Future Project: Commonwealth Department of Education, Science and Training. Gilbert, Jane (2003) ‘“New” Knowledges and “New” Ways of Knowing: Implications and Opportunities. Educating For the 21st Century: Rethinking the Educational Outcomes we want for Young New Zealanders. NZCER Conference Proceedings. Wellington, August 2003. Gillespie, Marilyn K (2002) EFF Research Principle: An Approach to Teaching and Learning That Builds Expertise. Equipped for the Future Research to Practice Note 2. Downloaded from www.nifl.gov/lincs/collections/eff/masters/02research-practice.pdf Grace, Gerald (1990) ‘The NZ Treasury and the Commodification of Education’. NZ Education Policy Today. Wellington : Allen & Unwin. Hager, Paul (1997) Learning in the Workplace: Review of Research. Australian National Training Authority, Leebrook: National Centre for Vocational Educational Research. Hargreaves, David H (2004) Learning for Life: The foundations for lifelong learning. Bristol: The Policy Press. Harpaz, Yoram (no date) Teaching and Learning in a Community of Thinking. (Paper circulated to the Ministry of Education reference group for skills, attitudes and values). Higgens, Jane and Dalziel, Paul (2002) Experience and Suitability of Job Applicants: Two policy issues from a survey of employers. Labour Market Bulletin 2000-02. Wellington: Department of Labour Himona, Ross Nepia (ed.) (2000) “Radical Doubt and Rangatiratanga: Questioning the unquestioned”. Te Putatara: A newsletter for the kumara vine. Wellington: Te Aute Publications. This is not a statement of government policy. The views expressed in this document are not necessarily those held by the Ministry of Education. Thoughts on what students need to learn at school: Summary for discussion purposes Accessed from http://www.tki.org.nz/r/nzcurriculum/references_e.php © Ministry of Education – copying restricted to use by New Zealand education sector Page 14 of 20 Hipkins, Rosemary and Vaughan, Karen (2002) Learning Curves: Meeting student needs in an evolving qualifications regime: From Cabbages to Kings: A first report. Wellington: NZCER. International Labour Organisation (2002) Learning and Training for Work in the Knowledge Society. Report IV(I), International Labour Conference, 91st Session. Geneva: International Labour Office. Kearns, Peter (2001) Review of Research: Key Competencies for the New Economy. Adelaide: National Centre for Vocational Educational Research. Kelly, Frances (2001) ‘Defining and Selecting Key Competencies: A New Zealand Perspective’. Definition and Selection of Competencies (DeSeCo): Theoretical and Conceptual Foundations. Paris: OECD. King, David (2003) “Jobs: Fading in the Middle”. The Press. Christchurch. Lashlie, Celia (2004) The Good Man Project. Unpublished paper Lauder, Hugh (1990) ‘The New Right Revolution’ in New Zealand Education Policy Today. Lauder, Hugh; Middleton, Sue; Boston, Jonathon; and Wylie, Cathy (1988) ‘The Third Wave: a critique of the NZ Treasury’s Report on Education’. New Zealand Journal of Education Studies, 23(1). Le Metais, Joanna (2003) New Zealand Stocktake: An International Critique. United Kingdom: National Foundation for Educational Research. Maani, Sholeh A. (2003) School Leaving, Labour Supply and Tertiary Educaiton Choices of Young Adults: An Economic Analysis Utilising the 19771995 Christchurch Health and Development Surveys. Treasury Working Paper 00/3. Macdonald, Marilyn (2003) Cognitive, Academic and Personality Characteristics of Early School Leavers and Persisters. SSTA Research Centre Report #92-03. Downloaded from http://www.ssta.sk.ca/research/school_improvement/92-03.htm Marshall, James D (1990) ‘The New Vocationalism’ in Education Policy in New Zealand: the 1990s and beyond. Marshall, James; Peters, Michael; and Smith, Graham Hingangaroa (1991) “The Business Roundtable and the Privatisation of Education: Individualism and the attack on Māori” in Education Policy and the Changing Role of the State: proceedings of the New Zealand Association for Research in Education seminar on education policy. Massey University, July 1990 / edited by Liz Gordon and John Codd. Palmerston North : Delta, Dept of Education, Massey University. Delta Studies in Education, no. 1: 81-98 This is not a statement of government policy. The views expressed in this document are not necessarily those held by the Ministry of Education. Thoughts on what students need to learn at school: Summary for discussion purposes Accessed from http://www.tki.org.nz/r/nzcurriculum/references_e.php © Ministry of Education – copying restricted to use by New Zealand education sector Page 15 of 20 McKay, Kristin (2001) ‘Equipping Children for Future Shock’. Education Today, issue 2 2001, Term 2. McPeck (1990) Teaching Critical Thinking. Philosophy of Education Research Library. New York: Routledge. McPherson, Mervyl (2004) ‘Cohort Vulnerability to Lack of Extended Family Support: The implications for social policy’. Social Policy Journal of New Zealand (21) March 2004. Mead, Hirini (2003) Tikanga Māori : Living by Māori Values. Wellington : Huia. Medford, Liz (2003) Employer Skills Survey: Employers say to graduates – ethics more important than creativity. Media Release, 30 October 2003, Victoria University of Wellington. Ministry of Education (1996) Te Whāriki Early Childhood Curriculum. Wellington: Learning Media. Ministry of Education (1997) New Zealand Curriculum Framework. Wellington: Learning Media. Ministry of Education (2001a) Pasifika Education Plan. Wellington, Ministry of Education. Downloaded from http://www.minedu.govt.nz/web/downloadable/dl4711_v1/2001-pasifikaeducation-plan-2001.pdf Ministry of Education (2001b) Assessing Knowledge and Skills for Life: First results from the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA 2000) NZ Summary Report, Wellington: Ministry of Education. Ministry of Education (2002a) New Zealand Schools Ngā Kura o Aotearoa 2002: A Report on the Compulsory Schools Sector in New Zealand. Downloaded from www.minedu.govt.nz Ministry of Education (2002b) Ngā Haeata Mātauranga: Annual report on Māori education 2000/01 and direction for 2002. Wellington: Ministry of Education. Ministry of Education (2002c) Skills and Education: Discussion paper for October 2002 Business-Government Forum. Downloaded from http://bbb.minedu.govt.nz/print_doc.cfm?layout=document&documentid=7872 &indexid=1108&indexparentid=2107&fromprint=y Ministry of Education (2003a) Curriculum Stocktake Report. Wellington: Ministry of Education. Ministry of Education (2003b) Learning for Living: Draft Background Paper: Key Competencies for the NZ Tertiary Education Sector. Unpublished draft paper. This is not a statement of government policy. The views expressed in this document are not necessarily those held by the Ministry of Education. Thoughts on what students need to learn at school: Summary for discussion purposes Accessed from http://www.tki.org.nz/r/nzcurriculum/references_e.php © Ministry of Education – copying restricted to use by New Zealand education sector Page 16 of 20 Ministry of Education (2003c) Schooling Strategy Discussion Document. Ministry of Education (2004a). Focus on Maori Achievement in Reading Literacy: Results from PISA 2000. Wellington: Comparative Education Research Unit, Research Division, Ministry of Education. Ministry of Education (2004b). Focus on Pasifika Achievement in Reading Literacy: Results from PISA 2000. Wellington: Comparative Education Research Unit, Research Division, Ministry of Education. Ministry of Education (2004c) Māori Development, Māori Language and Bilingual Education. Unpublished draft paper. Ministry of Education (2004d) Statement of Intent 2004-2009. Wellington: Ministry of Education. Ministry of Social Development (2003) The Social Report. Downloaded from http://socialreport.msd.govt.nz/documents/sr-social-connectedness.doc Ministry of Social Development (2004) Investing in Social Capital: The contribution of networks and civic norms to social and economic development. Draft working paper, May 2004. Misko, Josie (1995) Transfer: Using Learning in New Contexts. Adelaide: National Centre for Vocational Educational Research. Moeke, Trevor (1997) ‘The Importance of Capability in Improving Education Outcomes for Māori’ . Capability: Educating for Life and Work. Wellington: ETSA. Moy, Janelle (1999) The Impact of Generic Competencies on Workplace Performance: Review of Research. Leebrook: National Centre for Vocational Educational Research. National Centre for Vocational Educational Research (NCVER) (2002a) Building skills for the future: Emerging issues and possible responses. Leabrook: National Centre for Vocational Educational Research. National Centre for Vocational Educational Research (NCVER) (2002b) Building skills for the future: Key factors influencing the demand for skills. Leabrook National Centre for Vocational Educational Research. National Centre for Vocational Educational Research (NCVER) (2002c) ‘At a Glance’. Issues Affecting Skill Demand and Supply in Australia’s Education and Training Sector. Leabrook: National Centre for Vocational Educational Research. National Educational Monitoring Programme Downloaded from http://nemp.otago.ac.nz This is not a statement of government policy. The views expressed in this document are not necessarily those held by the Ministry of Education. Thoughts on what students need to learn at school: Summary for discussion purposes Accessed from http://www.tki.org.nz/r/nzcurriculum/references_e.php © Ministry of Education – copying restricted to use by New Zealand education sector Page 17 of 20 New Zealand Council for Educational Research (2004) Learning Curves: Meeting Student Learning Needs in an Evolving Qualifications Regime: Shared Pathways and Multiple Tracks: A Second Report (2004). Wellington: New Zealand Council for Educational Research. Nutthall, Graeme and Alton-Lee, Adrienne (1994) ‘How Pupils Learn’. SET Item 3 No.2 1994. Oates, Tim (2001) ‘Key Skills/Key Competencies – avoiding the pitfalls of current initiatives’. DeSeCo Additional Expert Opinions. Paris: OECD. OECD (2001) Definition and Selection of Competencies (DeSeCo): Theoretical and Conceptual Foundations: Background Paper. Downloaded from http://www.statistik.admin.ch/stat_ch/ber15/deseco/deseco_backgrpaper_dec 01.pdf OECD (2002) Definition and Selection of Competencies (DeSeCo): Theoretical and Conceptual Foundations: Strategy Paper. Downloaded from http://www.statistik.admin.ch/stat_ch/ber15/deseco/deseco_strategy_paper_fi nal.pdf OECD (2003) Learners for Life: student approaches to learning: results from PISA 2000. Cordula Artelt ...[et al]. Paris : OECD. Paulson, Karen (2001) ‘Using Competencies to Connect the Workplace and Post Secondary Education’. New Directions for Institutional Research, no 110, Summer 2001. Payne, Jonathan (2000) ‘The Unbearable Lightness of Skill’. Journal of Education Policy, 15(3). UK: Taylor and Francis Ltd. Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA 2000) Learners for Life: Student Approaches to Learning. Paris: OECD. Downloaded from http://www.pisa.oecd.org/Docs/Download/LearnersForLifeEXE.pdf Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA 2000) Downloaded from www.minedu.govt.nz/goto/pisa Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS-01), IEA. Downloaded from www.minedu.govt.nz/goto/pirls Putnam, Robert D (2000) Bowling Alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon and Schuster. Russell, Alice (2004) ‘Pillars of Wisdom’. The Age. Downloaded from http//theage.com.au/articles/2004/08/02/10912986150066.html?oneclick=true Salagnik, L; Rychen, D; Moser, U; Konstant, J (1999) Projects on Competencies in the OECD context: Analysis of Theoretical and Conceptual Foundations. Paris: OECD. This is not a statement of government policy. The views expressed in this document are not necessarily those held by the Ministry of Education. Thoughts on what students need to learn at school: Summary for discussion purposes Accessed from http://www.tki.org.nz/r/nzcurriculum/references_e.php © Ministry of Education – copying restricted to use by New Zealand education sector Page 18 of 20 Snook, Ivan (1996) ‘The Education Forum and the Curriculum Framework’. DELTA 48(1) 47-56. Snook, Ivan (1996) ‘Reflecting on the roles of enterprise’. Education Review July 10, 1996. Spady, William G (no date): OBE: Reform in Search of a Definition. Breakthrough Learning Systems, USA. (Paper circulated to the Ministry of Education reference group for skills, attitudes and values). Stevenson, B.S.; Black, T.E.; Christensen, I.S.; Durie, A.E.; Durie, M.H.; Fitzgerald, E.D.; Forster, M.E.; Rolls, K.R. and Taiapa, J.T. (2001) Best Outcomes for Māori: Te Hoe Nuku Roa Māori profiles project. Wellington: Te Puni Kōkiri. Te Puni Kōkiri (2000) Survey of Attitudes, Values and Beliefs towards the Māori Language. Wellington: Te Puni Kōkiri. http://www.tpk.govt.nz/publications/docs/survfull.pdf Te Puni Kōkiri (2002) The Use of Māori in the Family. Wellington: Te Puni Kōkiri. Temple, Jonathan (2000) Growth effects of education and social capital in the OECD countries. OECD Economics Department Working Papers 263, OECD Economics Department. Tomlinson, Mike (2004) !4-19 Curriculum and Qualifications Reform: Interim Report of the Working Group on 14-19 Reform. Downloaded from www.1419reform.gov.uk Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (1998) Downloaded from www.minedu.govt.nz/goto/timss Turner, Dave (2002) Employability Skills Development in the United Kingdom. Australian National Training Agency. Leabrook: National Centre for Vocational Educational Research. Tuuta, M; Bradnam, L; Hynds, A; Higgens, J; with Broughton, R (2004) Evaluation of the Te Kauhua Māori Mainstream Pilot Project: Report to the Ministry of Education. Wellington: Ministry of Education. Uchida, Donna, with Cetron, Marvin and McKenzie, Floretta (2003) Preparing Students for the 21st Century. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Education. Ullrich, Gilbert (2003) ‘Time to Trade Up’. Management. November 2003. Urlich-Cloher, D. & M. Hōhepa (1996) ‘Te Tū a Te Kōhanga Reo i Waenmga i te Whānau’. He Pūkenga Kōrero 1(2). Warner, Carl (2004) Adolescent Transitions From School to Employment: Working Paper No 12. Auckland: Massey University. This is not a statement of government policy. The views expressed in this document are not necessarily those held by the Ministry of Education. Thoughts on what students need to learn at school: Summary for discussion purposes Accessed from http://www.tki.org.nz/r/nzcurriculum/references_e.php © Ministry of Education – copying restricted to use by New Zealand education sector Page 19 of 20 Willis, S and Kissane, B (1997) Achieving Outcome Based Education: Premises, Principles and Implications for Curriculum and Assessment. ACSA. Willms, John Douglas (2003) Student Engagement at School: A Sense of Belonging and Participation: Results from PISA 2000. Paris: OECD. Downloaded from http://www.pisa.oecd.org/Docs/download/StudentEngagement.pdf Zodgekar, Arvind (2000) ‘Implications of New Zealand’s Aging Population for Human Support and Health Funding’. New Zealand Population Review, 26(1):99-113. This is not a statement of government policy. The views expressed in this document are not necessarily those held by the Ministry of Education. Thoughts on what students need to learn at school: Summary for discussion purposes Accessed from http://www.tki.org.nz/r/nzcurriculum/references_e.php © Ministry of Education – copying restricted to use by New Zealand education sector Page 20 of 20