The Existentialist Challenge: Who are we? Why are we here? How

advertisement

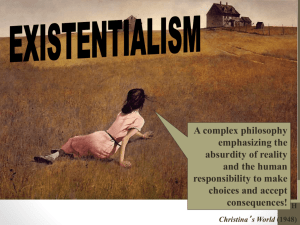

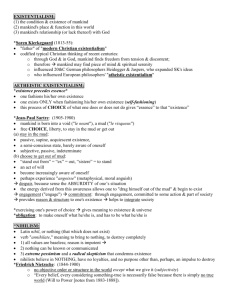

The Existentialist Challenge: Who are we? Why are we here? How do we make meaning in our lives? Existentialism is the 20th century extension of the Enlightenment Movement. Where the Enlightenment challenged and doubted God and morality, existentialism denies their existence. If God and morality do not exist then man is alone and free, except that this freedom imposes its own constraints. If man is free then it is wrong to deprive him of that freedom, and this extends to influencing others in their lives and the choice they make. In denying human nature, the philosophy claims that each of us creates our own essence through free action – humans are whatever they make themselves, we create our own nature through free, responsible choices and actions. Any kind of predestination laid out by God or nature is rejected, and thus the individual has no given basis on which to form beliefs. The absence of a predesigned moral order reflects the absurdity of life and entails the individual’s complete freedom. Humans must decide for themselves what their actions will be, and then take full responsibility for their choices. Only be assuming this freedom can one live authentically. Existentialism gained momentum as a result of World War II, whose devastation and destruction gave a sense of immediacy to questions about the purpose of living. Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980) saw humans as “condemned to be free.” We are free because we can rely neither on a God (who he believes does NOT exist) nor on society to justify our actions or to tell us what we essentially are. We are condemned because without a fixed purpose or a guideline we must suffer the agony of our own decision making and the anguish of its consequences. Humans are free but we must take full responsibility not only for our actions but also for our beliefs, feelings and attitudes. To illustrate, many people believe that we have little control over our emotions. If we feel depressed, we feel depressed, and there is little we can do about it. Sartre argued that if we are depressed, we have often chosen to be. Emotions, he said, are not moods that come over us but are often ways in which we freely choose to perceive that world and to participate in it. It is the consciousness of this freedom and its accompanying responsibilities that causes our anguish. The most anguishing thought of all is that we are responsible for ourselves. Sometimes we escape this anguish by pretending we are not free. For example, we pretend that our genes or our environment is the cause of what we are, or that we are spectators rather than participants, passive rather than active. When we so pretend, said Sartre, we act in “bad faith.” Self-deception or bad faith is the attempt to avoid anguish by pretending to ourselves that we are not free. We have many ways to do this. We try to convince ourselves that outside influences have shaped our nature or that forces beyond our control or unconscious mental states have shaped us. Clearly, existentialism provides a profound challenge to traditional views of human nature. If existentialism is correct, then there is no such thing as a universal human nature shared by all people. Humans are not made for anything. We simply exist, and each of us must decide for ourselves what purpose our existence will serve. There is no way to say ahead of time that one purpose is right for everyone. We are, therefore, ultimately responsible for our own nature and purposes. This radical responsibility – our inability to blame anyone else for what we are – is the basis for our feelings of despair, fear, guilt, and isolation. It is also the basis for our uncertainties and anxieties about death. There we confront the meaningless that is at the core of existence and thus discover a truth that enables us to live fully conscious of what being human means. 6 Basic Themes of Existentialism 1. Existence precedes essence. Man is a conscious subject, rather than a thing to be predicted or manipulated; he exists as a conscious being, and not in accordance with any definition, essence, generalization or system. Existentialism evolves as an inquiry into 'man's being'. This being has no fixed definition except that its “essence” cannot be found apart, but “lies in its existence.” Human nature is defined in the process of being expressed. 2. Anxiety (or the sense of anguish): the dread of the nothingness of human existence It is the belief that anguish is the underlying, all-pervasive, universal condition of human existence. Existentialists agree with certain streams of thought in Judaism and Christianity which view human existence as fallen, and human life as living in suffering and sin, guilt and anxiety. 3. Absurdity: "I am my own existence, but this existence is absurd". To exist as a human being is inexplicable and wholly absurd. Each of us is simply here, thrown into this time and place - for no reason, without necessary connection to anything. 4. Nothingness (or the void): We exist in relation to nothing. 5. Death: the unaware person tries to live as if death is not actual, he tries to escape its reality. Some existentialists believe that death is the most authentic, significant moment, one's personal potentiality, which one alone must suffer. If one takes death into their life, acknowledge it, and face it squarely, one will free themselves from the anxiety of death and the pettiness of life - and only then will one be free to become themselves. Death is as absurd as birth - it is no ultimate, authentic moment of one's life, it is nothing but the wiping out of one's existence as conscious being. Death is only another witness to the absurdity of human existence. The possibility of death isolates individuals because it continuously weighs upon existence - to understand this possibility means to decide for it, to acknowledge "the possibility of the impossibility of any existence at all" and to live for death. 6. Alienation (or estrangement): the alienation of individuals who pursue their own desires in estrangement from the actual institutional workings of society.