Writing separately - The Lawyers` Committee for Civil Rights and

advertisement

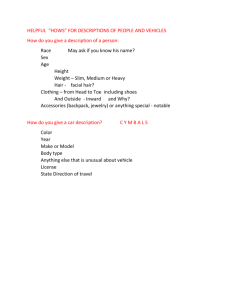

LAWYERS' COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS AND ECONOMIC JUSTICE 294 WASHINGTON STREET, SUITE 443 BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS 02108 TEL (617) 482-1145 FAX (617) 482-4392 VIA EMAIL November 20, 2015 Dear conferees, As you work in conference on the surface transportation reauthorization bills, we at the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights and Economic Justice urge you not to legislate the use of hair specimen drug testing for bus and truck drivers. The test is not reliable, producing positive test results based on environmental exposure rather than actual ingestion. Moreover, such false positives fall disproportionately on African Americans, due to the nature and texture of their hair. Instead, we hope that you will allow the scientists at the Department of Health and Human Services to engage in their regulatory review of proposed testing procedures. That review should take place first in order to avoid imposing unfair and discriminatory testing on any job applicant. The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights is a non-profit, non- partisan legal organization, founded by President Kennedy in 1963 to enlist the private bar in the fight against race discrimination and racial violence. The Boston branch, where I am a staff attorney, was founded five years later. It played a significant role in desegregating public housing and public schools in that city. The Boston Lawyers’ Committee, the Jewish Alliance for Law and Social Action, the Massachusetts Association of Minority Law Enforcement Officers, the Vulcans, representing minority firefighters, join and endorse the November 12, 2015 letter sent to you by the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, the National Workrights Institute, and other organizations that protect our civil rights and civil liberties. We share their concern that hair specimen drug testing has a clear discriminatory effect on African Americans due to the nature and texture of their hair. Unlike other workplace challenges confronted by African Americans, false positive hair test results cannot be avoided, prevented, or remedied. Legislating the use of this test to screen bus and truck drivers will surely result in unfairly disqualifying viable African American job applicants. For that reason, the hair drug test must be ranked among the many barriers that prevent equal employment opportunity in the workplace. The Federal government should be the last employer in the United States to even contemplate adopting such a discriminatory employment requirement. Cocaine is present in small amounts in the air and on common objects like dollar bills. It can easily find its way to the hair on anyone’s head. The hair specimen drug test is generally unreliable because it cannot distinguish between cocaine in the hair due to drug use and cocaine that is present from innocent contamination. African Americans are the most likely victims of this unreliability. Because African American hair is drier, more brittle, and contains more melanin than typical Caucasian hair, it both captures and retains more cocaine from the external environment than does Caucasian hair. The cocaine chemically binds to melanin in the hair shaft, making it impossible to obtain complete decontamination unless the hair is vigorously washed within the first hour. Although the vendors of this hair test claim to remove the melanin after liquefying the hair, experts have shown that only ten percent of the contamination is routinely removed through that process.1 As co-counsel in a federal employment discrimination case currently before the First Circuit Court of Appeals, we at the Lawyers’ Committee are well aware of the devastating consequences of using hair specimen testing to make critical employment decisions.2 We have brought suit against the Boston Police Department, on behalf of ten African American plaintiffs, for its continued use of a hair drug test that has cost the livelihood and reputation of dozens of long-serving officers. Between 1999 and 2006, African American police officers and applicants were five times as likely to test positive for cocaine use as their white counterparts.3 The First Circuit determined that it was extremely unlikely that this disparity was due to chance.4 In fact, Dr. David Kidwell, nationally recognized research toxicologist at the United States Naval Laboratory, has reviewed the litigation packets of four of the plaintiffs and concluded that the cocaine positive test results were most likely from environmental contamination.5 Many of our clients in this and other lawsuits challenging the hair specimen drug test are highly commended patrol officers with decades of valorous service to the Boston Police Department. They adamantly deny the use of illicit drugs, and nothing apart from this single uncorroborated test indicates that they are, in fact, substance abusers. The impact on their community is momentous. Fewer African American police are hired and African American veteran officers are terminated for no reason other than the results of this flawed hair specimen drug test. When local, state and federal employers use this test, the results efface the hard fought equal employment victories of the civil rights legislation. National and international toxicologists have long considered the hair specimen drug test to be too unreliable to be used as the basis for critical hiring and firing decisions without further corroboration of drug use. We urge the conferees to heed their warning. Yours truly, Laura Maslow-Armand, Esq. 1 Robert E. Joseph, Jr., Tsung-Ping Sue & Edward J. Cone. In Vitro Binding Studies of Drugs to Hair: Influence of Melanin and Lipids on Cocaine Binding to Caucasoid and Africoid Hair, 20 J. OF ANALYTICAL TOXICOLOGY, Oct. 1996, at 338, 343. 2 Jones v. City of Boston, No. CV 05-11832-DPW, 2015 WL 4689428, at *1 (D. Mass. Aug. 6, 2015)(appeal filed). 3 Jones v. City of Boston, 752 F.3d 38, 44 (1st Cir. 2014) 4 Id. at 35. 5 Affidavits of Dr. David Kidwell for Ronnie Jones, Richard Beckers, Shawn Harris and Walter Washington prepared for litigation at the Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination in 2003 and 2004.