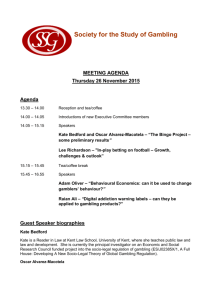

informing the 2015 gambling harm needs

advertisement