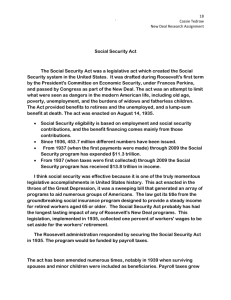

here - Columbia University Journal of Politics & Society

advertisement