B 28i4.5 December 2014

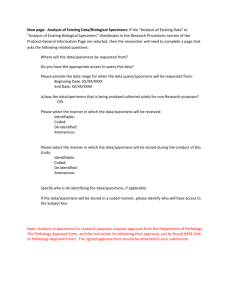

advertisement