RUNNING HEAD: JOINT ATTENTION 1 JOINT ATTENTION Joint

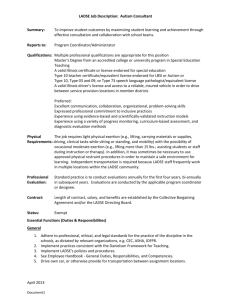

advertisement

RUNNING HEAD: JOINT ATTENTION 1 Joint attention in preschoolers Beth Reed Virginia Commonwealth University JOINT ATTENTION 2 Introduction There are a variety of challenges that arise for people diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder. Children with autism frequently have difficulty with the ability to establish appropriate social relationships. Smith (2013), considers that, “Social-emotional development is believed to be foundational to the development of cognition, language, and adaptive life skills (Smith, 2013, p. 395)”. One of the most evident weaknesses in social-emotional competence occurs with the struggle to establish joint attention with other people. According to Wong and Kasari, 2012, joint attention is “the ability to shift attention between another person and an object or event” (p. 2152). Pointing at a common item, engaging in eye contact with the speaker, and looking back to the item are some the specific skills needed to be successful with joint attention (Wong, 2013). Teaching preschoolers to engage in joint attention will help them to relate and communicate more closely with people in their lives. Furthermore, learning joint attention skills early on can assist in the formation of social relationships and theory of mind later in development (Warreyn & Roeyers, 2014). Guiding the review of this literature is the following question: To what extent will teacher-guided intervention impact a child’s ability to establish joint attention during a one-toone activity? A research was conducted to find articles relating to joint attention and preschoolers. Many articles were discovered in several databases. The VCU libraries search engine was the first place I discovered an abundance of articles. I initially searched everything with the key words: joint attention and preschool. Once I noticed a vast amount of information in need of narrowing down, I checked the limiters of peer-reviewed and restricted the articles to being published with the past five years. Limiting the articles to peer-reviewed is essential in order to JOINT ATTENTION 3 have quality, accurate material. Interventions for children with autism are constantly evolving, therefore, using the most recent information, within the last five years, would supply me with the most up-to-date research. I began opening articles to read the abstract and was able to eliminate several publications because the studies focused on toddlers and/or school-age children and my target age group is preschoolers. Several of the articles were not an actual study, yet an overview of joint attention; those works were excluded as well. The Google Scholar database is another place I chose to use to access articles on joint attention and preschoolers. When I struggled to open an article I input the name of the article into the VCU Libraries database and read the article within the EBSCOhost. I selected articles that specifically focused on interventions that were shown to increase joint attention. The Case-Smith (2013) article helped me to review several approaches contained in one article, which saved me time and also described a variety of interventions. Within the reference list of the Case-Smith (2013) article, I was able to find an author’s name I had noticed several searches prior, which led me to investigate articles with the name C. Kasari as an author. Article Review In all three studies, the chosen participants all had a diagnosis of ASD (Autism Spectrum Disorder) and were between three and seven years of age. Each group had an average total of 45 participants, which makes the testing population comparable across articles. Wong (2013), chose to gathered children from a large via fliers from the school district and local autism workshops and conferences. Rehabilitation centers were used as a source to find participants in the Warreyn and Roeyers (2013), study and Wong and Kasari (2012), found their preschoolers in a suburban, JOINT ATTENTION 4 public early childhood program. Although the amount of participants and the autism identification link the studies, the impact of the results could possibly vary based upon the fact that the children were recruited from dissimilar settings. Observations, rating scales, play assessments, and teacher surveys were used as methods to collect data for 1 month to acquire data about joint attention (Wong & Kasari, 2012). Researchers collected data on specified teacher and child behaviors within a 45 minute block of observation time in structured and unstructured settings (Wong, 2013). Both researchers and the adults responsible for implementing the intervention contributed to the gathering of the research obtained from the methods provided. Teacher-guided interventions had different meanings across the articles for this review. Developmental and behavioral techniques were used along with positive social reinforcement in small group or one-to-one type settings. In another study a familiar adult to the child was given a training package which contained the guidelines for the intervention where they were encouraged to participate in two 30 minutes sessions per week with their given child (Warreyn & Roeyers, 2013). By way of a person the child already knows, such as a teacher or therapist, the intervention creates a naturalistic approach in its implementation. Imbedding joint attention strategies into classroom activities with the guidance of a treatment manual was used in one study. The teachers had the choice to implement the intervention one to one, in small groups, or as a whole class (Wong, 2013). Two of the articles talked about similar teacher-guided interventions, whereas the third article simply observed a setting to witness how joint attention skills were address naturally by the teacher. The findings from two of the studies show that teacher-directed joint attention interventions do have a positive impact on joint attention skills in preschoolers with autism. JOINT ATTENTION 5 Increase in joint attention quality was noted on four study points across 12 months according to Lawton and Kasri (2012). The Warreyn and Roeyers (2013) research showed that the experimental group, exposed to the intervention, made more progress than the control group for joint attention. Because the teachers were not given a specific intervention in the Wong and Kasri (2012) article, joint attention skills were rarely reinforced within the classroom environment. The results signify that with specific training and/or intervention joint attention skills can increase. Children with autism tend to initiate fewer joint attention skills, and teachers tend to respond to acts of joint attention more so in structured activities (Wong and Kasri, 2012). Consequently, structured interventions, provided by trained teachers, would likely increase a preschooler with autism’s joint attention skills. The limitations of the included articles include the possibility of teacher and therapists not completing all of the forms, checklists, and surveys due to the amount of time it may take (Warreyn and Roeyers, 2013). Taking into consideration that teacher and child variables may possibly influence the effectiveness of the intervention could be another limitation (Wong, 2013). The long-term effects of the attained joint attention skills and the ability to generalize the skill across settings and people should be demonstrated in future longitudinal studies. Once researchers are able to determine the effects the interventions have on a child’s future social skills then we can truly say the methods are successful. Future research in joint attention and preschoolers with autism is needed because as we ascertain more about how children with autism learn we are opening new doors to interventions. Finding a solid, data-driven intervention to aide in the growth of joint attention skills will guide a child’s team toward successful implementation of that skill. Parents, speech pathologists, occupational therapists, and early childhood educators can benefit from research-based JOINT ATTENTION interventions to implement with young children with autism. When a child is able to establish joint attention with another person his/her world opens up into a new realm of communication and socialization. Teacher-guided interventions to promote joint attention have been proven to work, therefore an increase in the awareness of these interventions should be spread throughout the early childhood intervention community. Responsiveness on the part of the community allows for an increase in implementation and an overall growth in joint attention skills for preschoolers with autism. 6 JOINT ATTENTION 7 References Case-Smith, J. (2013). Systematic review of interventions to promote social–emotional development in young children with or at risk for disability. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 67, 395–404. Lawton, K., & Kasari, C. (2012). Brief report: Longitudinal improvements in the quality of join attention in preschool children with autism. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 42(2), 307-312. Warreyn, P., & Roeyers, H. (2014). See what I see, do as I do: Promoting joint attention and imitation in preschoolers with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 18(6), 658-671. Wong, C., and Kasari C. "Play and joint attention of children with autism in the preschool special education classroom." Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 42.10 (2012): 2152-2161.