Mentors as Buffers to Ambient Racial Discrimination

advertisement

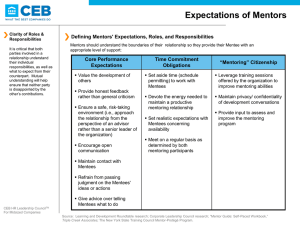

MENTORS AS BUFFERS TO AMBIENT RACIAL DISCRIMINATION Employees do not have to be the direct target of discrimination to feel its pernicious effects. Indirect exposure to discrimination, also called ambient discrimination, can have a profound effect on workers (Glomb et al., 1997; Hitlan, Schneider, & Walsh, 2006). Ambient discrimination involves the knowledge or awareness of discrimination aimed at others in the workplace (Chrobot-Mason, Ragins, &Linnehan, 2013; Glomb et al., 1997). Mentoring theorists have long held that mentors can buffer employees from the negative effects of a discriminatory workplace (Blake-Beard, Murrell, & Thomas, 2007; Ragins, 1989, 2002, 2007), but have not tested this hypothesis or examined its underlying processes. Addressing this need, we integrate theoretical work from the relationships literature (Kahn, 1998, 2001), to examine the buffering effect and explain how it occurs. We also examine whether mentors are unique in their ability to buffer, or whether other work relationships can also buffer employees from the negative effects of ambient discrimination. Drawing on relational systems theory (Kahn, 1998), we view mentoring as a type of anchoring relationship. Anchoring relationships are positive work relationships that attach employees to organizations in times of stress (Kahn, 1998, 2001). These relationships provide a unique set of skilled therapeutic holding behaviors that can buffer employees from adverse experiences and help them maintain their commitment to the organization, even when faced with emotionally disturbing, confusing or anxiety-producing events (Kahn, 1998, 2001). Holding behaviors extend well beyond basic forms of social support or traditional mentoring functions. They involve a set of skilled behaviors that help receivers recover their ego integrity when faced with situations marked by anxiety. Integrating theory and research from clinical psychology, group relations, and family systems theory, Kahn (2001) presents a framework of holding behaviors at work. According to this framework, providers can offer three types of holding behaviors: 1) they provide containment by signaling their accessibility and by offering receivers a safe space to share their experiences, feelings and reactions; 2) they provide empathic acknowledgement by accepting and 1 validating receivers’ feelings of conflict, confusion and inadequacy; and 3) they offer enabling perspectives that help receivers make sense of the situation and rebuild their ego integrity within a nonjudgmental and validating context. Using Kahn’s (2001) framework of holding behaviors, we first developed and validated a 9-item measure of relational holding behaviors at work using a sample of 262 employees. We then used this measure to test the hypothesis that holding behaviors would moderate the negative relationship between ambient racial discrimination and work outcomes involving organizational commitment and stress. Our hypotheses were tested in a national sample of 557 workers. Since our measure was designed to assess holding behaviors provided by mentors, supervisors and coworkers, we also explored whether supervisors and coworkers could also buffer employees from the negative effects of a discriminatory workplace. We found that mentors buffer employees from the adverse effects of ambient discrimination by providing holding behaviors. Protégés who received higher levels of holding behaviors from their mentors were less likely to experience the negative effects of ambient discrimination on organizational commitment. This finding held for those with formal as well as informal mentors, despite the fact that formal mentors provided lower levels of holding behaviors. Mentors’ holding behaviors also buffered employees from the effects of ambient discrimination on stress-related outcomes, although this effect was stronger for those with informal mentors. Employees exposed to racial discrimination at work reported more physical symptoms of stress at work, more insomnia, and higher rates of stress-related absenteeism, but they reported less of these effects when they had informal mentors who provided holding behaviors. Formal mentors providing holding behaviors were also able to buffer protégés from the effects of ambient discrimination on physical symptoms of stress, but this effect did not extend to insomnia or stress-related absenteeism. We found that these buffering effects held across protégé race for all of the outcomes examined. We also found that buffering is unique to mentoring relationships. Supervisors and close 2 coworkers were unable to buffer employees from the effects of ambient discrimination. Supervisors provided lower levels of holding behaviors than both informal and formal mentors, and their holding behaviors did not moderate the relationship between ambient discrimination and any of the outcomes. Close coworkers offered comparable levels of holding behaviors as formal and informal mentors, but coworkers’ holding behaviors also failed to moderate the relationships between ambient discrimination and outcomes. In short, irrespective of their level of holding behaviors, supervisors and coworkers were unable to deflect the detrimental effects of ambient discrimination.Our exploratory analysis revealed that conceptually related mentoring functions, (i.e., friendship) generally failed to buffer employees from the negative effects of ambient discrimination. Traditional functions may reflect the behaviors mentors routinely use, but may fail to capture the more skilled set of behaviors that mentors can employ to help their protégés cope with confusing or anxiety-producing experiences at work. Holding behaviors may therefore offer a useful complement to traditional mentoring functions. General forms of social support also failed to buffer, supporting the idea that effective buffering requires a match between the demands of the situation and the type of support provided in the relationship (Cohen & Wills, 1985; Thoits, 2011). Our finding that holding behaviors were only effective when they were provided by mentors offers the idea that, like a “Rubik’s cube”, effective buffering requires a combination that matches not only the type of support with the demands of the situation, but also the source of support. In sum, these results suggest that mentors may provide more than traditional mentoring function. Mentoring theorists have long contended that mentoring is more than just a supportive work relationship (Allen & Eby, 2007; Kram, 1985; Ragins & Kram, 2007), and these results support this assertion. Our results also point to the importance of incorporating relational quality in comparisons of formal and informal relationships. Formal mentors who provided holding behaviors were able to buffer their protégés from the negative effects of ambient racial discrimination which suggests that mentoringprovides an important relational refuge in discriminatory workplaces. References 3 Allen, T. D., & Eby, L. T. (Eds.). (2007). The Blackwell handbook of mentoring: A multiple perspectives approach. Malden, MA: Blackwell. Blake-Beard, S., Murrell, A., & Thomas, D. (2007). Unfinished business: The impact of race on understanding mentoring relationships. In B. R. Ragins & K. E. Kram (Eds.), The handbook of mentoring at work: Theory, research and practice (pp. 223-247). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Chrobot-Mason, D., Ragins, B., &Linnehan, F. (2013). Second hand smoke: Ambient racial harassment at work. Journal of Managerial Psychology. 23 (5), 470-491. Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985).Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis.Psychological Bulletin, 98, 310-357. Glomb, T., Richman, W., Hulin, C., Drasgow, F., Schneider, K., & Fitzgerald, L. (1997). Ambient sexual harassment: An integrated model of antecedents and consequences. Organizational Behavior & Human Decision Processes, 71, 309-328. Hitlan, R. T., Schneider, K. T., & Walsh, B. M. (2006). Upsetting behavior: Reactions to personal and bystander sexual harassment experiences. Sex Roles, 55, 187-195. Kahn, W. A. (1998).Relational systems at work.In B. M. Staw& L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior (pp. 39-76). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Kahn, W. A. (2001). Holding environments at work. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 37, 260279. Kram, K. E. (1985). Mentoring at work. Glenview, IL: Scott Foresman. Ragins, B. R. (1989). Barriers to mentoring: The female manager's dilemma. Human Relations, 42, 122. Ragins, B. R. (2002). Understanding diversified mentoring relationships: Definitions, challenges and strategies. In D. Clutterbuck & B. R. Ragins (Eds.), Mentoring and diversity: An international perspective (pp.23-53). Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. Ragins, B. R. (2007). Diversity and workplace mentoring relationships: A review and positive social capital approach. In T. D. Allen & L. T. Eby (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of mentoring: A multiple perspectives approach (pp. 281-300). Oxford: Blackwell. Ragins, B. R., & Kram, K. E. (2007). The roots and meaning of mentoring. In B. R. Ragins & K. E. Kram (Eds.), The handbook of mentoring at work: Theory, research, and practice (pp.3-15). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Thoits, P. A. (2011). Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health.Journal of Health & Social Behavior, 52, 145-161. 4