CHRONIC INFLAMMATORY DEMYELINATING

advertisement

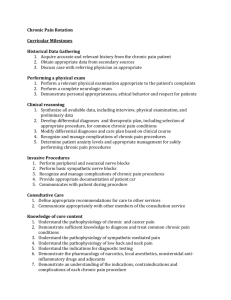

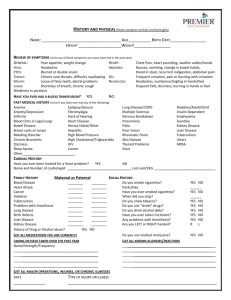

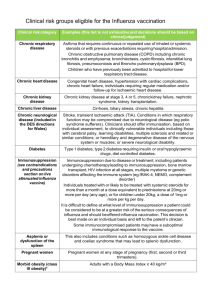

CHRONIC INFLAMMATORY DEMYELINATING POLYNEUROPATHY: A CASE HIGHLIGHTING IGNORANCE-DRIVEN ETHICAL DILEMMA IN RESOURCE-POOR SETTINGS Introduction Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP) is an acquired immune-mediated disorder of peripheral nerves and nerve roots. CIDP is closely related to Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) and it is considered the chronic counterpart of that acute disease. CIDP is less common in children than in adults.1 In Japan, the prevalence rate per 100 000 was 1.61 in the total population; 2.01 in males and 1.23 in females.1 The age dependent prevalence rate was 0.23 in children less than 15 years old. Using the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) criteria, the prevalence was 1.97 per 100,000 in this population similar to the prevalence among caucasians.1 Although, the exact prevalence is not known among African children, there is an apparently similar immunopathologic basis among different races.1,2 The specific cause of CIPD has not been identified but there is evidence for its immunologic origin.2 The cellular immunity is involved through T-cell activation and expression of cytokines while the humoral immunity via deposition of immunoglobulin and complements on myelinated nerve fibers.2 The classic form of CIDP manifests a fairly symmetric, predominant motor involvement of the lower limbs and the deep tendon reflexes are usually reduced or absent.3 Sensory involvement is common Sensory impairment in CIDP is usually greater for vibration and position sense than for pain and temperature sense, reflecting the involvement of larger myelinated fibers.4 Cranial nerve and bulbar involvement occur in about 10 percent of patients. Constipation and urinary retention are found in late presentation and severe cases.3,4 Most patients with CIDP exhibit a slowly progressive course, but a relapsing-remitting course occurs in at least one-third, and more common in younger patients.4 Electrophysiologic features of CIDP include partial conduction block, reduction of conduction velocity and compound motor action potential (CMAP) amplitude while common histologic features are segmental demyelination, onion bulb formation and axonal degeneration.5 Other relevant investigations include cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis and MRI of spinal roots, brachial plexus, and lumbosacral plexus.6 Stringent research criteria of CIDP used in clinical trials often miss the diagnosis in routine clinical practice leading to late diagnosis and treatment.7,8 Hence, it is preferable to use clinically oriented tool like the Koski criteria which has specificity and positive predictive value comparable to both the AAN research criteria and the European Federation of Neurological Societies/Peripheral Nerve Society (EFNS/PNS) electrodiagnostic criteria.8 The standard therapies for CIDP are intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG), corticosteroids and plasma exchange, but about 15% of cases are treatment refactory.9, In a large series, prognosis of CIPD varies from complete remission in 26%, partial recovery in 61% to severe disability in 13%.10 Like other chronic illnesses, the outcome of CIPD can be influenced by the progression of the disease itself, , carers’ perception of its aetiology, poverty and sociocultural practices.11 We recently managed a case that shows an intriguing relationship between such external factors and the outcome of this rare chronic neurological disorder. Case Report A nine year old girl (D.T.) was admitted into the paediatric Neurology unit of the University of Benin Teaching Hospital, Nigeria on the 7th September 2011 with Hospital Number 546192. She was a bright primary 3 pupil, first of two children of nonconsanguineous parents in social class V. She first presented in the setting of an upper respiratory tract infection 3 years earlier when the mother noticed a change in her gait and difficulty with climbing stairs. Two weeks later, she was admitted due to inability to walk and urinary incontinence. Neurologic findings were conclusive of a lower motor neuron lesion. The initial assessment was GBS with a differential diagnosis of transverse myelitis. CSF analysis showed < 5 white blood cells per mm3, no red blood cells, glucose 52mg/dl and protein of 49mg/dl. MRI of the spinal cord, electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction studies could not be done due to financial constraints. Similarly, plasma exchange and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) therapies were not achievable. She was closely monitored and her vital capacity was consistently >20ml/kg. She received physical and occupational therapies but remained bedridden till the third week on admission when she was commenced on oral prednisolone 1mg/kg/day, as a suspected chronic variant of GBS. However, she was discharged against medical advice (DAMA) few days later, despite social service intervention. She was taken to a traditional healer on a superstitious basis. Five months into the illness, she recovered partially at home, walking with a limp till this relapse. She was lost to follow up. In this second episode, she re-presented with a seven month history of slowly progressive upper and lower limbs weakness and urinary incontinence; fever and drowsiness occurred a week before presentation. On examination, she was febrile (Temperature – 38.50c) with multiple septic decubitus ulcers (grade 2-4, figure 1c). Neurological examinations revealed altered consciousness (GCS–7/15), hypotonia, areflexia and zero power in the lower limbs; hyporeflexia and grade 3 power in the upper limbs. There was loss of pain and vibration sensations up to T4. The diagnosis was septicemia in a child with CIDP. Neuroimaging, EMG/Nerve conduction studies, plasma exchanges and IVG’s therapies were not achieved due to inadequate financial resource. Lumbosacral radiograph was normal (figure 1a & b) and retroviral screen was negative. She was managed with intravenous ceftazidine at 150mg/kg/day, gentamin at 5mg/kg/day and supportive care, but sepsis screen later yielded Kliebsiella species sensitive only to piperacillin–tazobactam. Fifth day on admission, she had gasping respiration, pulse rate of 46 beats per minute moderate volume, and percutaneous oxygen saturation of 52%. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation was commenced but she succumbed to the illness before transfer to the intensive care unit. Parents declined post-mortem examination. 1a 1b 1c Figure 1(a): Lumbosacral radiograph AP view of a 9 year old girl with CIDP showing normal vertebral bodies and pedicles; (b) lateral view showing normal vertebral bodies and spinal processes; (c) infected stage IV decubitus ulcer in the same patient after DAMA. Discussion CIDP is a rare immune-mediated disease in childhood, especially in West Africa sub-region due to the skew of health care delivery towards control of infectious diseases while chronic neurologic disorders may be neglected in rural populations. Our patient manifested typical neurologic features of CIDP following a GBS-like presentation. In a relapsing course, she had symmetric reduction in deep tendon reflexes, sensory loss and autonomic dysfunction fulfilling the mandatory clinical criteria of the European childhood CIPD consortium.12 Also, we confirmed the diagnosis of CIPD in this case based on her clinical features that fulfilled the Koski criteria which has comparable validity to both the AAN and EPNS/PNS research criteria.6-8 As found in this patient, cytoalbumin dissociation may occur in up to 90% of CIDP cases.13 Nerve biopsy for histology, NCV, MRI and genetic studies in selected cases are useful in excluding differential diagnosis of CIDP.6 This were not done in this case due to parents limited financial resources and adherence to fictitious beliefs of “spiritual” or superhuman origin of unremitting illnesses leading to refusal of care.11, Treatment options in CIDP include corticosteroid which was initiated fourth week into the illness but was rejected a few days later before any significant response. Considering common side effects of steroids including impaired wound healing and immune suppression, specific therapies of sepsis and stabilization were the priorities in her management on re-admission with extensive decubitus ulcers and lethargy, following a 3-year long default. Parents could not afford IVIG and plasma exchanges. She succumbed a few days later apparently due to metastatic complications of Kliebsiella septicemia and/or progression of CIDP. Poor prognostic factors in CIDP include a treatment refractory course, respiratory compromise, CNS involvement and severe co-morbidities.10 Moreover, resorting to harmful traditional remedies, late presentation and low socioeconomic status of the carers contributed to poor outcome in this case. Although a legal injunction can be obtained to admit a child after parents’ presumptuous refusal of treatment despite adequate counseling, current level of implementation of free health care in our setting focuses on short-term treatment of acute childhood illnesses precluding chronic neurological disorders.14,15 Hence, as in this case, the clinician is sometimes in a dilemma concerning provision of guardianship for an ill child without access to free health services, if parents declined treatment on erroneous basis.14,15 As illustrated in this case, the outcome of CIDP and other chronic disorders in childhood in resources-poor settings often hinges on parents’ socio-economic status and belief systems in spite of clinicians’ advocacy. References 1. Iijima M, Koike H, Hattori N, Tamakoshi A, Katsuno M, Tanaka F, Yamamoto M, Arimura K, Sobue G, Prevalence and incidence rates of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy in the Japanese population Refractory Peripheral Neuropathy Study Group of Japan. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008; 79 (9):1040. 2. .Rezania K, Gundogdu B, Soliven B. Pathogenesis of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy. Front Biosci. 2004; 9:939-45. 3. Saperstein DS, Katz JS, Amato AA, Barohn RJ. Clinical spectrum of chronic acquired demyelinating polyneuropathies. Muscle Nerve. 2001;24(3):311-24. 4. McCombe PA, Pollard JD, McLeod JG. Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy. A clinical and electrophysiological study of 92 cases. Brain. 1987;110 ( Pt 6):1617-30. 5. Harbo T, Andersen H, Jakobsen J. Length-dependent weakness and electrophysiological signs of secondary axonal loss in chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy. Muscle Nerve. 2008;38(2):1036-45. 6. Joint Task Force of the EFNS and the PNS. European Federation of Neurological Societies/Peripheral Nerve Society Guideline on management of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy: report of a joint task force of the European Federation of Neurological Societies and the Peripheral Nerve Society--First Revision. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2010; 15(1):1-9. 7. Rajabally YA, Nicolas G, Pi?ret F, Bouche P, Van den Bergh PY Validity of diagnostic criteria for chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy: a multicentre European study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009; 80(12):1364-8. 8. Koski CL, Baumgarten M, Magder LS, Barohn RJ, Goldstein J, et al. Derivation and validation of diagnostic criteria for chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. J Neurol Sci. 2009; 277(1-2):1-8. 9. Hughes R, Bensa S, Willison H, Van den Bergh P, Comi G,et al, Inflammatory Neuropathy Cause and Treatment (INCAT) Group. Randomized controlled trial of intravenous immunoglobulin versus oral prednisolone in chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy. Ann Neurol 2001; 50(2):195-201. 10. Kuwabara S, Misawa S, Mori M, Tamura N, Kubota M, Hattori T. Long term prognosis of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy: a five year follow up of 38 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006; 77(1):66-70. 11. Ojuawo A. Ignorance Driven Ethical Dilemmas. In Azubike JC, Nkanginieme KEO (2nd eds). Paediatrics and Child Health in a Tropical Region. African Educational Services, Owerri, 2007:136-143. 12. Nevo Y, Topaloglu. 88th ENMC international workshop: childhood chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (including revised diagnostic criteria), Naarden, The Netherlands, December 8-10, 2000. Neuromuscul Disord. 2002; 12(2):195-200. 13. Barohn RJ, Kissel JT, Warmolts JR, Mendell JR. Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy. Clinical characteristics, course, and recommendations for diagnostic criteria. Arch Neurol. 1989;46(8):878-84 14. UNICEF: UNICEF Factsheet on the Child's Rights Act in Nigeria. Accessed on www.unicef.org/wcaro/WCARO_Nigeria_Factsheets_CRA.pdf on 29th September 2011. 15. NHIS: Guideline for Public Sector and Organized Private Sector. Accessed http://www.nhis.gov.ng/index. on 29th September 2011.