the oscholars - WordPress.com

advertisement

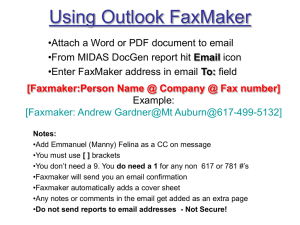

THE CRITIC AS CRITIC AUGUST 2013 Review by Joellen Masters ‘Anders Zorn: A European Artist Seduces America,’ Hostetter Gallery, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, February 28 – May 13, 2013. According to his obituary in the October 16, 1920 American Art News, Anders Zorn was ‘a cosmopolitan in an age when cosmopolitans are becoming scarce in number despite the shrinkage of the world and the closer communion of the great nations of the earth’ (5). Born in 1860, Zorn was raised by his maternal grandparents in Mora, the small Swedish village which would become the respite in ‘his lifelong wanderlust’ (Facos 37).1 Zorn’s parents had met in Stockholm where his mother worked in a brewery; shortly afterward, his father, a prosperous brewery master, abandoned the young and unmarried woman. In 1875, the precociously talented Zorn moved to Stockholm and enrolled at the Royal Academy of Art until 1881 when, frustrated by the Academy’s conventional methods and rigid views, he discontinued his studies and moved to London. It was in England that Zorn learned the art of etching, a genre that saw a rebirth in the nineteenth century. Zorn became one of the most celebrated artists of this form, and the etching’s reproducible nature fueled his rapidly developing reputation.2 It was in London, too, that Zorn began his lucrative career painting portraits, the genre that would ensure his financial success and repute in the United States. By the time he first met Isabella Stewart Gardner at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893, Zorn was a prestigious and highly visible presence in the European art market and a rival for John Singer Sargent in commissioned portraits. His celebrity had faded considerably by the Great War, and at his death in August 22, 1920, he was almost forgotten.3 Today he is regarded as a minor artist, virtually unrecognized outside of his native country. Anne Hawley, the Gardner Museum’s director, says this perception occludes the rich variety in Zorn’s output, continuing to split appreciation between European collectors who knew him for his nudes and rural genre scenes, and the American clientele Zorn cultivated so assiduously and who sat for his portraits (Director’s Foreword 7). The recent special exhibition at the Gardner Museum in Boston, ‘Anders Zorn: A European Artist Seduces America,’ set itself the commendable mission to restore the Swedish artist’s diminished fame.4 This intelligent show was the debut exhibit by Oliver Tostmann, who joined the Gardner’s curatorial staff in April 2011,5 and the first historic exhibition in the Museum’s new Renzo Piano-designed wing, the sleek glass and steel modern addition that opened in January 2012. The show combined Zorn works from the Gardner’s rich holdings with those on loan, some for the first time, from institutions such as the Goteborgs Konstmuseum, the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm, and the Zorn Museum in Mora. As Tostmann notes, only two American exhibitions in the last twenty-five years have made the Swedish artist their focus.6 The Boston show’s restrained presentation took a modest step in making Anders Zorn better known in the United States. Tostmann juxtaposed versions of Zorn’s paintings; he set etchings side-by-side with their larger oil renditions; he combined all to illustrate the wide range in Zorn’s artistic curiosity, methodical process, and creative output. Rather than following a presentation scheme that would contain Zorn’s works within a biographical and linear narrative, Tostmann divided the Hostetter Gallery’s intimate space into five distinct wall areas, arranging the representative works by category rather than chronological period. Zorn was a belle époque painter in demand by the period’s key art collectors, a savvy ‘entrepreneur who was always looking for new clients’ and ‘a self-made man who figured out early how to operate in the modern art world,’ skilled at creating works for distinct exhibition and gallery spaces and in employing styles and content his time viewed as particularly ‘modernist’ (Tostmann 8).7 To that end, the curatorial choice beautifully showcased Zorn’s efforts with genre and subject throughout his many years of professional activity. Tostmann launched us immediately into Zorn’s celebrity and, more importantly, his great friendship with Isabella Stewart Gardner. ‘Zorn and Gardner,’ the gallery’s opening room, provided a welcoming space for the viewer. An enormous reproduction of a 1920 photograph of the sixty-year-old Zorn on the handsome deep blue wall showed him prosperous and mustachioed, dressed in his artist’s smock, seated in his Mora studio with his Yorkshire terrier Mouche at his side. He gazed coolly from under the wall’s stenciled quotation from the New York Journal, October 10, 1900: ‘Zorn, A Prince of Art, is Again Our Visitor.’8 The quotation set a nicely self-referential tone and justification for the display, reminding us of the Museum’s mission with its exhibit, and Gardner’s great affection and professional promotion for the Swedish painter.9 This anterior gallery space showcased their relationship with examples such as the lovely 1894 pencil and red chalk on paper study for Gardner’s face, an image no more than three inches across, but entrancing and sweet. Zorn captures Gardner in an alert, inquisitive expression; her parted lips and rounded softness in her face enhance the portrait’s charm. Several etchings here introduced viewers to his immense ease with the medium. Gardner’s first commission to Zorn had been an etched portrait in 1894 that, as the descriptive label explained, with its coat-of-arms decorated drape and Gardner dressed in a fur cape and seated in a neoclassicalstyle chair, depict her as a ‘status-conscious member of the American upper class.’ Reading, another 1894 etching, is an exquisite rendering of matrimonial harmony. Charles Deening, the wealthy Chicago businessman and Zorn’s best American patron, highlighted in the background, smokes his pipe, while his wife, Marion, sits reading to him in a delicately shadowed foreground. An 1890 etching, Zorn and His Wife, one of several artist ‘portraits’ in the show, further illustrated his astonishing skill with line. Zorn and His Wife, 1890 (etching), Zorn, Anders Leonard (1860-1920) / © Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, MA, USA / The Bridgeman Art Library Posed in the left foreground, with an etching needle in his right hand and a sheaf of papers in his left and on the table before him, Zorn gazes out and beyond the viewer. His serious expression is in line with that of his wife, Emma, who stands self-confidently behind him and before the perpendicular framing lines of an interior door . . . or, perhaps, a canvas on an easel Below this grouping, a single glass case displayed various personal objects, such as the 1894 cartoon drawing Zorn made of Gardner, ‘The Madonna of the Charity,’ a good-humored commentary on her warm support for musicians, artists, and writers. Selected photographs showed the Gardners and the Zorns floating in gondolas during the autumn 1894 visit Anders and his wife Emma made to the Palazzo Barbaro which the Gardners rented for their many trips to Venice. 10 A few letters from Zorn to Gardner typified their spirited correspondence with Zorn’s often embellished with his lively illustrations.11 In a 1904 note, for instance, written when he returned to Europe after his fifth American visit, Zorn sketched himself in the foreground, weeping and weighted down with luggage, while a stick-figure of Gardner in the background waves farewell from her Greenhill country home in Brookline. The case included Christian Eriksson’s silver soap box, a commission arranged by Zorn for Gardner in 1895. Art Nouveau in style, the handle for the soap box’s lid is fashioned like a young girl who bathes in the rippling silver watery surface that seems to spill down the square sides.12 Included, too, was the cablegram Gardner received in late August 1920 from their mutual friend, Hjalmar Lundbohm, notifying her that Zorn had died. Unfortunately, in comparison to the lavish vitrines and cabinets in Fenway Court’s older and original spaces, cloaked in velvet covers that tempt the viewer with the promise of hidden delights, this single case made a pallid imitation of those Gardner herself had put together. Nonetheless the display case’s prudent selection gave a glimpse into the special camaraderie between two figures whose ‘origins could hardly have been more different, he the illegitimate son of a Swedish peasant and Isabella Stewart Gardner, the daughter of a wealthy industrialist’ (Facos 36), a closeness further demonstrated with the several portraits in this room. In December 1898, Zorn made his third trip to America. When he learned that Jack Gardner had died early in that month, Zorn moved in with the grieving Isabella and set up his studio in her Back Bay home. The six portraits of Gardner relatives and friends he painted during this sojourn suggest Zorn’s sensitive understanding of the powerful curative effect his work could bring to the recently widowed Gardner who was grateful for the companionship of her ‘very dear and delightful’ Swedish friend. The exhibit displayed four of these, ‘each,’ as Gardner explained in a letter to a friend, ‘perfect in its way’ (qtd. in European Artist 153). All reflect the leisurely upper-class Boston life but in deceptively simple compositions. Martha Dana, later Mrs. William R. Mercer (1899), a protégée of Gardner’s, sets the beautiful young woman against a bare background that highlights the tailored femininity in her high-collared shirtwaist blouse, close-fitting black jacket, and small hat with its red flower that compliments rather than hides the delicate contours in her face. In Joseph Randolph Coolidge (1899), the male subject – Jack Gardner’s brother-in-law – commands the portrait’s three-quarter space. What Tostmann defines as Zorn’s ‘deliberately limited palette (consisting of [his] signature colors of ochre, white, black, and red)’ (‘International Success’ 21) augments the restrained richness in Coolidge’s dark suit and his deep blue bow-tie. He holds in his right hand a red piece from Halma, the board game that this prominent Boston figure had invented. Most striking, perhaps, is George Peabody Gardner (1899), a handsome full-length image of Jack Gardner’s nephew set opposite Zorn’s photograph. Gardner stands and leans, like the cue stick to his right, against a green felt-covered billiard table. The male figure’s strong vertical presence in the canvas’s center splits the composition. As with the other portraits, Zorn limits the background’s detail. Flat swaths of brown and deep cream throw into greater prominence Gardner’s masculine self-assurance. The sophisticated grey shades in his suit with its long frock coat, the deep navy cravat, the casual drape in his gold watch chain all contribute to the image’s understated force. Together, the portraits signified that in 1898 and 1899 Zorn was indeed, again, ‘our visitor’; they iterated Zorn’s centrality in the familial context of Isabella Stewart Gardner’s Boston world and displayed his great talents with portraiture. Viewers could enter the Hostetter Gallery’s larger section from the right or the left. Either way we were greeted by the portrait, Isabella Stewart Gardner in Venice (1894) which hung on its own small wall in the room’s middle. This masterful design decision contributed a delightful effect in its continued emphasis of Zorn’s relationship with Gardner and its reminder that the luxurious installations in Gardner’s Fenway rooms and residence lie adjacent to the impersonal modernity of the Museum’s new wing. Zorn painted this lyrical portrait during the visit he and his wife made to the Palazzo Barbaro in 1894.13 In it, Gardner has turned away from watching the fireworks over the Grand Canal outside her window and steps back into the salon. Mrs Gardner (1860-1920) in Venice, 1894 (oil on canvas), Zorn, Anders Leonard (1860-1920) / © Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, MA, USA / The Bridgeman Art Library Zorn portrays the middle-aged Gardner in a joyful moment – the strong contrasts between her shimmering white evening dress and pearl necklace and the deep dark space behind and around the figure emphasize his hostess’s radiant personality. His great skill with light effects shows in how he renders Gardner’s hands whose palms and outstretched fingers reflect in the glass panes they touch. Tostmann’s audio commentary made the especially marvelous point that the reflections both anchor and suspend Gardner in a floating and light-filled moment.14 Hanging directly opposite this welcoming portrait, was the selection ‘Artists’ Studios,’ a grouping of paintings and etchings of artists at work. The arrangement functioned as yet another engaging tribute to Gardner’s keen love for the arts, her pleasure in collecting, and her hope that her Fenway Court museum would be ‘for the education and enjoyment of the public forever.’15 The small etching Augustus Saint-Gaudens II (1897) suggests ‘an intimate boudoir scene’ (JNN and OT, Catalog 136) with the artist in collar and cuffs seated on a bedside while behind him his naked female model curls in the shadows created by Zorn’s clear lines. The harmonizing diagonals in Saint-Gaudens’ posture and the woman’s torso and legs unite the two in more than an inspirational bond. Both In Wikström’s Studio (1899) and Self-Portrait (1889) more conventionally represent artists and their work spaces. Zorn varies his brushstrokes and his muted monochromatic palette in his painting of the sculptor Emil Wikström’s atelier. Thick forceful applications of grey create the heavy clay model on the canvas’s left and lower side and enclose the nude model who stands in the studio. The moment is private – the model seems lost in thought. The inanimate clay and stone frame her radiant warmth, an effect Zorn creates with softer and less visible applications of paint. Zorn’s Self-Portrait, done ten years before, is a testament to both his artistic self-regard and his international reputation. Zorn painted Self-Portrait for the Uffizi Gallery in Florence which commissioned it for its collection of artists’ self-portraits but at a time when his career had not yet achieved the international scope it soon would. Zorn shows himself as both painter and sculptor. The crowded composition arranges the artist in the canvas’s right half while the left-hand foreground shows his work-inprogress, the clay bust of his wife Emma, and, behind, the back of a canvas signed ‘Zorn.’ The blended greys and beiges in Zorn’s suit, vest, clay, and canvas unite the artist with his creations even while the ruddy pinks in his complexion and his concentrated gaze separate him from the dull tones and blind gaze in the statue’s face. The touch of red so noticeable in Zorn’s many paintings, appears here, too, as a single small stroke on his lapel. It is the badge he had received recently for his 1889 induction into the French Legion of Honor. The paintings on the third wall, labeled ‘Society Portraits,’ emphasized their female sitters’ wealth and social standing, not unlike those by Zorn’s contemporary, John Singer Sargent. Zorn’s approach, however, differed significantly from the American painter’s – his ‘quick, sweeping brushstroke’ (Curator’s Label) always effected a vibrant animation, in startling contrast to Sargent’s ‘delicate fragility’ (Tostmann 17). Mrs. Potter Palmer (1893) shows Berthe Honoré Palmer, Chicago’s celebrated society hostess, dressed in a shimmering gown with a long train, crowned with a starry tiara and holding a delicate wand-like scepter, speaking before the Board of Lady Managers of the Women’s Building at the 1893 World’s Fair. Palmer knew Isabella Stewart Gardner and, like her Boston friend, was a keen supporter of the arts. In 1890 she had purchased Zorn’s painting The Small Brewery, and, when she knew he would be in Chicago as Sweden’s commissioner of fine art for the exhibition (A-ME, Catalog 89), made sure to arrange for the portrait. The painting’s vast scale (258 x 141.2 centimeters) emphasizes the stark contrast between the glimmering resplendent figure and the darkened background space to enhance the visual celebration for the ‘Empress of Chicago.’16 The portrait – not unlike the Chicago Exhibition itself – shows the mid-west capitol as a place of culture and advancements. A second painting, Mrs. Walter Rathbone Bacon (1897) portrays Virginia Bacon, sister-in-law to railway magnate Edward Rathbone Bacon seated with her arm around her collie dog. Zorn achieves a quiet intimacy and dignified tone by using a soft, light palette and brushstroke. Virginia’s face is lit by a gentle light from the right; she looks gracefully up at her viewer since Zorn adopts a perspective a bit higher than his sitter. The Bacon family became one of Zorn’s best American patrons and his work for them represented not only his recognition by the American industrial elite, but another triumph over Sargent who had painted Virginia the year before. Mrs. Walter Rathbone Bacon was exhibited in the 1897 Paris Salon where Zorn’s loose and light-filled image drew high critical acclaim (A-ME, Catalog 88). The etchings, small studies and larger paintings that comprised the show’s fourth section,’In the City,’ perhaps best fulfilled the exhibit’s mission and aspirations. Tostmann claims these urban scenes – only twelve – the ‘most ambitious’ in Zorn’s prolific career and illustrate his easy alignment with the Impressionist impulse to paint a quotidian modernity. Most were executed when Zorn and Emma lived in Paris from 1888-1896 (20). An exception is The Large Brewery (1890), powerful in its diagonal line of kerchiefed women workers on the right that stretches into the painting’s depth and that frames an empty gleaming space – perhaps the Stockholm brewery floor – that occupies most of the composition. Night Effect (1895), done in his singular color-combination of white, black, red, and ochre, shows a Parisian streetwalker, not an uncommon subject for late-nineteenth painters by any means; however, Tostmann states Zorn had his eye on an audience less accustomed to Paris’s café and nighttime scenes. He worked the topic out in different etched versions, two of which Gardner eventually owned (20). Positioned as it was in the exhibit, between Zorn’s American society portraits and his other urban scenes, the large painting created a provocative connection between subject matter and social environment. The prostitute staggers and reaches for a tree with her left hand while her right hitches up her red skirt, revealing her lacy petticoat. Her overly fancy red bonnet adds to the figure’s vague immodesty – what was often a slight crimson note in other works, is here the dominant tone. In the background is a café’s interior. In contrast to the women in the society portraits, the Parisian streetwalker is outside a room or home; yet, unlike the women in Zorn’s pastoral and nature paintings, she strikes an awkward pose, exaggerated by her tilted stance and the thick and hasty application of paint. ‘In the City’s’ crowning achievement was its showcasing of Zorn’s two finished versions of The Omnibus, brought together in public display for the first time. This engrossing section of the exhibit illustrated Zorn’s methodical process behind his finished oils in scrupulous and detailed evidence, and proved his canny business acumen about different art markets. As the scholarship has noted, Zorn loved riding the Paris streetcars and enjoyed sitting among the riders who came from all social classes.17 Several preliminary studies in oil and watercolor, as well as an 1892 etched version, demonstrated Zorn’s absorbed process and approach that resulted in the first finished oil painting in 1891-1892. A group of riders sits in a diagonal line that stretches into the canvas’s right-hand background. The young woman in the front holds on her lap a cumbersomely large square box. Short and swift brushstrokes evoke rather than carefully define the figures and faces. Zorn restricts his colors to whites, greys, and, most strikingly, black, reflecting his great admiration for Manet’s technique and palette.18 Pleased with the painting and its Paris reception, in late 1892 Zorn began the second version with a different audience and venue in mind: Chicago’s 1893 Exposition. Set side-by-side with the first version, the second shows significant differences. The smooth brushstroke produces careful and specific details in the figures’ postures and faces, especially that of the young woman in the foreground who is prettier, more refined, and, no longer alone in the foreground holding the oversize box, sits in a relaxed pose between a partially hidden male passenger and a female rider (also prettier). The rough white rectangular box has become more manageable – cylindrical and bound by a gleaming leather strap. The impressionistic black patches have evaporated, transformed into warmer and more varied tones; the vaguely rendered windows and interior are now sharper clearer panes and wooden frames The Omnibus, 1892 (oil on canvas), Zorn, Anders Leonard (1860-1920) / © Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, MA, USA / The Bridgeman Art Library This version of the painting plays a significant part in the Zorn and Gardner hagiographies. As Sweden’s commissioner of fine art for the Chicago World’s Fair, Zorn was in the United States to curate the great number of works on loan for the Exposition. Gardner, too, was in the city, having lent her picture of Saint Denis Cathedral by Paul Helleu for the momentous occasion. She saw The Omnibus, loved it, and bought it immediately for $1600 (OT, Catalog 98). Thus, began their long and stimulating friendship. Despite his affluent urbanity, Zorn spent many months each year in Stockholm and Mora, remaining loyal to ‘the peasant culture from which he came’ (Facos 3). He became pivotal in Sweden’s National Romanticism’s efforts to create a ‘collective awareness of Sweden’s unique and diverse natural and cultural heritages’ (6) by preserving its folklore and culture. He encouraged local crafts and arts production. He collected costumes and musical instruments and assisted in building a concert hall for lectures and performances of Swedish folk dance and music (9). According to Arvid Nyholm, a former student who visited Zorn in 1914 at his small home outside Mora, the artist who ‘reveled in the exclusive international social circles of industrial magnates and aristocrats throughout his life,’ who could name Sweden’s King Oscar II not only as a portrait subject but also a ‘favorite sailing companion’ (Facos 3), sat contentedly ‘whittling little wooden spoons,’ savoring a simple life ‘where everybody eats his porridge from a pewter plate with a wooden spoon and sleeps naked under a white, soft sheepskin cover in his bed in the wall’ (Nyholm 470). The exhibit’s fifth arrangement, ‘Rural Life,’ emphasized this abiding fidelity. It was one of the show’s loveliest groupings that included The Ice Skater, notable as both a first in the ice-skating genre to depict the activity at night and as an experiment in shadows for Zorn (Tostmann 110; 113). The Ice Skater’s stunning asymmetrical composition privileges a slightly higher point-of-view; we look down at the single female skater who stands (or leans) at a mild angle in the left foreground while shadows and unfocused shapes swirl on the ice and into the night behind her. Despite his dismay about The Ice Skater’s weak critical reception, Zorn loved this painting which he made that winter in Mora. Included here, too, were several works that show his light and graceful touch with nudes, a subject he began to explore in 1891 during a summer idyll in the Swedish countryside. The nude-in-nature image became a particularly potent symbol for Sweden’s National Romanticism’s vision. In Zorn’s hands, the subject becomes something more, circumventing the erotic and epitomizing the transcendent link between man and the natural world (Facos 6).19 Opal (1891), for instance, with its two women who recline amid a river bank’s leafy and sun-dappled greenery, romanticizes the conventional nineteenth-century female nude and rejects the New Woman’s fin-desiècle metropolitan independence.20 This lyrical simplicity is most evident in Morning Toilet (or With His Mother), the 1888 oil that became part of Isabella Stewart Gardner’s collection in 1896. Unlike the thick-impasto surface and short brushstroke technique he uses in Opal, Zorn applies his thinned oils with delicate and sheer brushstrokes. The Morning Toilet, 1888 (oil on canvas), Z orn, Anders Leonard (1860-1920) / © Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, MA, USA / The Bridgeman Art Library Working en plein air demanded Zorn paint quickly, and Morning Toilet’s glints and glimmers of light reflect off the surface of the lake. The equally luminous rocks along the shore embrace the nude woman who stands quietly in the water and leans down tenderly to steady her small rosy child. The image is naturally serene; the young mother and her child unself-conscious and content. Without question, ‘Anders Zorn: A European Artist Seduces America’ provided a pleasurably informative survey of Zorn’s oeuvre, most especially in the strong curatorial design that anchored all five of the distinct subject categories. The exhibit cultivated the solid understanding that Zorn’s fluency with genre, media, and technique, his experiments with composition and light, and his intelligent yet voluptuous eye for detail were consistent throughout his professional life. Various descriptive signs and label cards offered the basic information standard to any museum’s display; the succinct audio guide augmented that printed information in limited fashion. Those wishing for more will find the handsome reproductions and scholarly essays in the exhibition catalog richly satisfying particularly as the scrupulous attention the contributors pay to Zorn’s life and work fill in the many unfortunate – but, perhaps, inevitable – blanks in the show. Despite, however, the show’s heartfelt mission and skillful presentation, its lasting effect lingers as generally neutral. Most awkward was the unwitting paradox that this show constructed between two visions for a public museum: Isabel Stewart Gardner’s idiosyncratic and privately funded dream and the Museum’s unavoidably more corporate and commercial objective. Aside from the whimsical intimacy established by the gallery’s opening room and the strategically placed Venice portrait, the exhibit registered as tepidly cautious. The show lacked an exuberant and sensuous joy, i.e., those qualities Gardner evoked so skillfully in installations with many works the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum had selected and then rearranged for its own purposes in the recent display. As Alan Chong has noted, Gardner’s Fenway Court provided a totality in contrast to the ‘cold, isolating experiences provided by modern museums, which lacked emotion and failed to interact with the other arts. The Gardner Museum’s multisensory experience prevented visitors from analyzing any individual object in an intellectual fashion’ (‘Museum of Myth 216). Paintings such as The Omnibus, Morning Toilet, and Isabella Stewart Gardner in Venice – all owned by Gardner – first hung in the sumptuous spaces of Gardner’s Back Bay home and, later, in those of Fenway Court. Those interested are strongly encouraged to turn to Anne-Marie Eze’s splendid essay, ‘Zorn in Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner’s ‘Faithful Painter’,’ that makes superb use of original photographs that document the shifting places these specific paintings occupied within those richly ornamented interiors and explains Gardner’s meticulous eye for aesthetic harmony in textures, shapes, and natural light. Of course, Tostmann’s exhibit did not (and could never) attempt to recreate Isabella Stewart Gardner’s arrangements. Anyone wishing to indulge in the intoxications of the ‘treasure-trove’ in what Trevor Fairbrother has called the ‘knowing eclecticism of Mrs. Gardner’s installations’ (575) can stroll through the gleaming glass corridor that joins the new wing’s easy neutrality to the original building’s lush aesthetic. Nonetheless, the show seemed erroneously titled for the America it claimed it would ‘seduce’ very well might be still in thrall to the ‘suggestive, nonexpository museum’ (‘Museum of Myth 219) of its formidable founder. Acknowledgements I wish to thank M.T. Sharif for his keen proofreading commentary of this review’s initial draft. My special thanks to the College of General Studies at Boston University and Deans Natalie McKnight and Megan Sullivan for their assistance in providing funding for reproduction rights. All images used with the permission and courtesy of the Bridgeman Art Library in New York in conjunction with the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Let me add my gratitude to Tom Haggerty of the Bridgeman for his patience in helping me with the permissions process. Works Cited ‘Anders Zorn: A European Artist Seduces America, February 28 to May 13, 2013.’ Cur. Oliver Tostmann. Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Boston. 3 May 2013. Anders Zorn: A European Artist Seduces America, February 28-May 13, 2013. Web. http://www.gardnermuseum.org/collection/exhibitions/__exhibitions/anders__zorn. 21 June 2013. Carter, Morris. Isabella Stewart Gardner. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1925. Chong, Alan. ‘Anders Zorn (1860-1920).’ ‘The Palazzo Barbaro Circle.’ McCauley, Chong, Zorzi, and Lingner. 271-272. ---. ‘Artistic Life in Venice.’ McCauley, Chong, Zorzi, and Lingner. 87-128. ---. ‘Mrs. Gardner’s Museum of Myth.’ Museums: Crossing Boundaries. Spec. issue of Anthropology and Aesthetics 52 (2007): 212-220. JSTOR. Web. 13 May 2013. ---. ‘Mrs. Gardner’s Two Silver Boxes by Christian Eriksson and Anders Zorn.’ Cleveland Studies in the History of Art 8 (2003): 222-229. JSTOR. Web. 12 May 2013. Eze, Anne-Marie. ‘Zorn in Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner’s ‘Faithful Painter.’’ Tostmann, 55-65. Facos, Michelle. Swedish Impressionism’s Boston Champion: Anders Zorn and Isabella Stewart Gardner, May 4 to August 22, 1993. Exhibition Catalog. Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 1993. ---. ‘’The Unstudied, Unposed Naturalness of Life’: Zorn’s Bather Paintings.’ Tostmann, 41-53. Fairbrother, Trevor. ‘Museums in Massachusetts: Boston and Cambridge, MA.’ Review. The Burlington Magazine 146.1217 (2004): 575-577. JSTOR. Web. 12 May 2013. Hawley, Anne. ‘Director’s Foreward.’ Tostmann, 7. McCauley, Elizabeth Anne. ‘A Sentimental Traveler: Isabella Stewart Gardner in Venice.’ McCauley, Chong, Zorzi, and Lingner. 3-51. McCauley, Elizabeth Anne, Alan Chong, Rosella Mamoli Zorzi, and Richard Lingner. Gondola Days: Isabella Stewart Gardner and the Palazzo Barbaro Circle. Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2004. Nyholm, Arvid. ‘Anders Zorn: The Artist and the Man.’ Fine Arts Journal 31.4 (1914): 469-481. JSTOR. Web. 13 May 2013. Shand-Tucci, Douglass. The Art of Scandal: The Life and Times of Isabella Stewart Gardner. New York: HarperCollins, 1997. Tostmann, Oliver, ed. Anders Zorn: A European Artist Seduces America. London: Paul Holbertson, 2013. ---. ‘Anders Zorn and His International Success.’ Tostmann, 13-26. ---. ‘Curator’s Forward.’ Tostmann, 8-9. Zorn, Anders. The Morning Toilet. 1888. Oil on canvas. Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Reproduced by permission of the Bridgeman Art Library, New York. ---. Isabella Stewart Gardner in Venice. 1894. Oil on Canvas. Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Reproduced by permission of the Bridgeman Art Library, New York. ---. The Omnibus. 1892. Oil on canvas. Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Reproduced by permission of the Bridgeman Art Library, New York. ---. Zorn and His Wife. 1890. Etching. Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Reproduced by permission of the Bridgeman Art Library, New York. A specialist in Victorian Literature and Culture, Joellen Masters is a senior lecturer at Boston University. She is editor of THE LATCHKEY, a journal of New Woman studies. To return to the Table of Contents of THE CRITIC AS CRITIC, please click here To return to our home page, please click here. 1 Unless otherwise noted in the text, all information and quotations by Michelle Facos refer to Swedish Impressionism’s Boston Champion: Anders Zorn and Isabella Stewart Gardner, May 4 to August 22, 1993. Facos curated this exhibit which, as I say above and in note 6 below, was one of only two Zorn exhibits in the United States before this year’s at the Gardner Museum in Boston. 2 As the anonymous writer for Art in America’s obituary remarked, in 1920 Zorn’s fame “rests upon his etchings. His paintings are not easy to find, but the etchings are in every public museum” (5). 3 See Oliver Tostmann’s “Curator’s Foreword,” in the show’s catalog Anders Zorn: A European Artist Seduces America. Additional citations from Tostmann’s foreword will appear as “Curator’s Foreword” in the parenthetical citation; references to Tostmann’s scholarly essay in the book, “Anders Zorn and His International Success,” will be abbreviated as “International Success.” In addition, references to the catalog’s briefer analyses of individual works cite the writer’s initials, Catalog and page number – OT, for Oliver Tostmann, A-ME for Anne-Marie Eze, and JNN for Jessica Njeri Dnungu. 4 As readers can tell, the exhibition closed shortly before this review’s publication. 5 http://www.gardnermuseum.org/collection/exhibitions/- __exhibitions/anders__zorn 6 The first, “Zorn, Paintings, Graphics and Sculpture,” was in Birmingham, Alabama in 1986, and the second, curated by Michelle Facos, was the Gardner’s 1993 exhibit, “Swedish Impressionism’s Boston Champion: Anders Zorn and Isabella Stewart Gardner,” a show that used only works Gardner herself had owned. For a listing of Isabella Stewart Gardner’s complete Zorn holdings – paintings, drawings, letters, and so forth – see Anders Zorn: A European Artist Seduces America, 168-187. 7 Tostmann laces this point about Zorn’s shrewd marketing of his work throughout his finely persuasive essay “Anders Zorn and His International Success,” noting, for instance, that Zorn’s Paris urban genre scenes “catered to a clientele outside France” (20). 8 As the exhibit’s audio guide – modest in its explications and information – states, the American popular press had coined this title for Zorn who would make a total of six visits to the United States. 9 Gardner helped instigate Zorn’s American reputation, spearheading his shows at Boston galleries, including his two exhibits at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, the first in March 1894 when the museum was still in its Copley Square location (Eze 62) and the second, in 1899 when Gardner arranged for a show of sixteen portraits of “American sitters” Zorn had completed during one of his visits to Gardner in Boston (Facos 33). 10 As Alan Chong has noted, like so many others who traveled to Venice, Zorn found it inspiring. “Gondolas and gondoliers fascinated Zorn” and during his stay at the Palazzo Barbaro he made many sketches and oil studies of the canals, boats, and the men who rowed their passengers around the watery city (“Anders Zorn 1860-1920” 271). 11 The Gardner Museum’s archives hold sixty-three letters the Zorns wrote the Gardners, beginning in 1893 and concluding in 1923, three years after the painter’s death. Appendix 4 in Anders Zorn: A European Artist Seduces America reproduces all sixty-three and includes two Gardner wrote to Zorn’s widow, now in the archives of the Zorn Museum in Mora. 12 In 1903, when Fenway Court first opened, Gardner placed this lovely piece in the Dutch Cabinet, stashing it with many other silver objects, making it difficult to see its glorious whimsy and sophisticated craftsmanship. For a fascinating discussion of the box’s conception, see Chong’s essay “Mrs. Gardner’s Two Silver Boxes by Christian Eriksson and Anders Zorn.” 13 Gondola Days: Isabella Stewart Gardner and the Palazzo Barbaro Circle is a sumptuous collection of finely researched and illustrated essays. For example, Alan Chong’s “Artistic Life in Venice” includes Emma and Anders Zorn’s stay with the Gardners in its focus on the busy and stimulating social circle the American couple cultivated. Elizabeth Anne McCauley’s “A Sentimental Traveler: Isabella Stewart Gardner in Venice” describes the Boston hostess’s love for Italy and its influence on her collecting and on her eventual construction of Fenway Court. 14 In the catalog’s discussion, Tostmann persuasively explains the reflections create the sense that Gardner is one in a larger group of dancers, and links that effect to the maenads and their association with “eternal youth and powers of seduction” (80). Opinions about the portrait’s origin vary from the charmingly anecdotal in books such as Shand-Tucci’s The Art of Scandal: The Life and Times of Isabella Stewart Gardner, 149 and Morris Carter’s Isabella Stewart Gardner and Fenway Court, 147 to stringent scholarly arguments that trace influences in Zorn’s image and describe his creative process. See in addition to Tostmann’s discussion, Alan Chong in Gondola Days: Isabella Stewart Gardner and the Palazzo Barbaro Circle, 271. 15 I take this statement from Gardner’s will from “Mrs. Gardner’s Museum of Myth,” 214. 16 The title is one Emma Zorn assigned for the Chicago hostess although whether her ironic remark signifies any jealousy (Zorn was known for his sexual infidelities) is unclear. See “Catalog,” page 89, note 5. 17 See Facos’s thoughtful essay “’The Unstudied, Unposed Naturalness of Life’: Zorn’s Bather Paintings” in the exhibition catalog as well as Swedish Impressionist’s Boston Champion. 18 As she claims, like his Impressionist contemporary, Zorn “achieved masterful results with black” (24). Facos provides a convincing comparison between the second version of The Omnibus and English painter William Maw Egley’s 1889 Omnibus Life in London as a possible influence. 19 See also “’The Unstudied, Unposed Naturalness of Life’: Zorn’s Bather Paintings.” 20 Facos draws this observation about Zorn’s “anti- cosmopolitanism” from Nilsen Laurvik’s study of Zorn’s nudes. See “’The Unstudied, Unposed Naturalness of Life’: Zorn’s Bather Paintings,” page 53.