one

advertisement

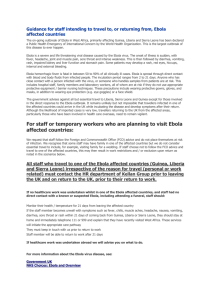

The magazine’s science journalist brings dramatic testimony from Liberia and Sierra Leone, hotbeds of ebola. At the heart of an epidemic 23/08/2014 ‘Only if the world helps us will we be able, in a few months’ time, to get this horrible disease under control.’ The current ebola epidemic is many times larger than ever before in the number of victims, the length of the outbreak, and the size of the territory affected. So far in West Africa, there have been 2,473 cases of ebola resulting in 1,350 deaths, writes Tanja Rudez. The current situation in Liberia is truly dramatic because of ebola. All of the appeals from international organisations such as Doctors Without Borders who are fighting on the frontlines treating patients in Liberia are more than justified. Many hospitals are closed because staff are infected with ebola. Some aviation companies have stopped flying to Liberia and many companies have shut down their operations there. Food and transport prices are rising so there are fears there could be unrest in this impoverished country, says Brigadier Predrag Mikolic, who has been in Liberia as a member of the UN Mission (UNMIL) since last November. Mikolic’s voice sounds a little tired. From early morning until evening, this Split resident who was first an army observer in Sierra Leone, then an officer in Afghanistan, then at NATO in Brussels is now dedicated to only one goal: to quench what has so far been the biggest and longest epidemic of ebola, one of the deadliest diseases for which mankind has neither vaccine nor medicine. It’s not only Brigadier Mikolic: many thousands of UN forces have set their priorities as stopping the epidemic of ebola in Liberia. False hope Heavily devastated by a bloody civil war, Liberia has been fighting a horrible battle for the past few months with the ebola virus, which has taken away 572 lives already out of 972 people it infected. ‘Ebola started in Liberia in March this year, after cases in Guinea and Sierra Leone were recorded. And just when it looked like we had the epidemic under control, because 42 days had passed since the last case, the disease reappeared,’ Mikolic tells me, and then explains how ebola started spreading again in May. ‘One woman was at a funeral in a distant part of the country when she got infected and transmitted the disease to Montcerrado county which Monrovia belongs to as well. One of the most frequent ways in which ebola spreads in Liberia is precisely through funerals because the tradition here is to have physical contact with the deceased,’ Mikolic explains. The fact that physical contact with infected people was key to spreading the disease was highlighted by Dr. Linda Rahal, a doctor from Freetown, capital of neighbouring Sierra Leone in which 374 have died out of 907 people infected so far. Linda Rahal was educated in the USA and now works for the World Health Organisation at the Ministry of Health of Sierra Leone. She spent Wednesday in areas hit by ebola and spoke to me on Thursday, just before a press conference in Freetown. No information ‘We are fighting with all our strength, but the ebola epidemic has a huge influence on our country’s society and economy,’ says Rahal. ‘The key for prevention of the ebola epidemic is information. The problem is that our people don’t understand information about ebola and don’t know how to turn it into protective measures. Also, in Sierra Leone the culture is predominantly closed, whereby people often touch themselves to express mutual closeness, and that only increases the spreading of the disease. That is the reason that ebola has spread so far,’ explained the African doctor. Although the impoverished countries of west Africa have been battling this deadly infectious disease for months, it looks like the developed world only become aware of ebola after a priest, Miguel Pajeras, died in a Madrid hospital, as the first European who was infected this year by helping patients with the disease. Many have faced the fact that in a globalised world, viruses and diseases are no longer limited to isolated areas of a jungle but instead thanks to intense airway traffic can travel with people from one part of the world to the other. Ebola has so far been limited to some isolated areas in Africa. It first appeared at the end of August 1976 in a Catholic mission in Yambuku, deep in the tropical forest about 1,000 km north of Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo (then Zaire). The first cases were noted in one village on the banks of the river Ebola: all of the infected people suddenly got a high temperature, headache, vomiting, diarrhoea, strong muscle pains, voluminous bleeding and finally organ failure. The mortality rate was high: of 318 cases, 280 ended fatally. In a small hospital run by Flemish nuns, 11 of 17 members of the medical staff died soon after. Risking his own life, a Belgian doctor and scientist, Dr Piter Piot, bravely headed to Yambuku with his colleagues. Soon they discovered that the key to the spreading of the infection was badly sterilised needles in the hospital and close contact of healthy people with the deceased just before the funeral. Piot and his colleagues set up a quarantine and microbiological analysis showed that the cause of the deadly infection was a virus. They called it ebola. ‘Intellectually the most exciting and at the same time terrifying aspect was the fact that we didn’t know at the time how the virus was being transmitted: air, food, mosquitoes, sexual contact, blood or water, which are the usual ways of transmitting a virus,’ Piot remembered in a conversation with Jutarnji List two years ago. ‘So it wasn’t clear how we were supposed to protect ourselves.’ Since that first instance of a new and terrifying disease, there have so far been 20 ebola epidemics. Given that these epidemics broke out in isolated African villages near tropical forests far from urban centres, the number of victims was mainly in the range of tens and sometimes hundreds of people. When the world media reported back in March on the first cases of ebola in Gueckedou prefecture in southern Guinea, it seemed that this epidemic would be also be limited to a narrow area. That was wrong: today we know that ebola in Guinea appeared towards the end of last year and its first victim was a two-year-old boy from the village of Meliandou in Gueckedou who died on the 6th of December 2013. Soon after, his mother and three-year-old sister also got the disease and died, and the villagers that were in contact with them spread the sinister virus to other villages. By the end of March, the World Health Organisation reported ebola in four districts of southern Guinea and the first cases in neighbouring Sierra Leone and Liberia. ‘This epidemic started in southeastern Guinea at the border with Liberia and Sierra Leone where there are many roads and dense traffic with many people crossing the borders. The epicentre of the epidemic was near urban centres so the human-to-human contact was much larger than in previous epidemics which were recorded in isolated villages whose citizens weren’t overly mobile,’ says Srdjan Matic, coordinator for environment and health in the regional office of the World Health Organisation in Europe. Since May this year, Liberia and Sierra Leone took the unenviable lead in the number of victims and during the summer the first cases of ebola have been recorded in Nigeria. ‘So far in west Africa, there have been 2,473 registered cases of ebola, of which 1,350 resulted in death,’ says Nyka Alexander, who is in charge of public relations at the WHO’s coordination centre for ebola, which is located in Conakry. The death of doctors The reasons for the seriousness of the current ebola epidemic, which is many times bigger than all previous ones in terms of the number of victims, length of the epidemic and the size of the territory it affects, the WHO experts also see in the fact that the heaviest-hit countries have modest or nonexistent public health services, so the conditions for an outbreak of any infectious disease is dramatically bigger than elsewhere. Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone are amongst the poorest countries in the world, and years of bloody conflicts and civil wars have destroyed their education and health systems. For example, in Liberia there is only one doctor per 100,000 citizens and in Sierra Leone there are 2. ‘The worst hit in Sierra Leone are Makena county, towards the border with Guinea, and the areas bordering Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia. This region is densely populated and very undeveloped, despite it being a hotbed of diamond mining,’ says Ivica Stankovic, a football manager from Johannesburg who lived in Sierra Leone from 1997 to 2003 and visited Liberia several times. ‘I worked for a humanitarian organisation, World Vision, and my permanent base was Freetown, but I was often in districts which are now hit with ebola. I have many friends there whom I am in contact with and for whom I fear. People in these countries have it hard anyway, and especially in such an extraordinary situation because they have neither the human resources nor the infrastructure to cope with ebola,’ says Stankovic. He also knew Dr. Sheikh Umar Khan, leader of an expert team for fighting ebola in Sierra Leone, who recently died himself from this terrifying disease. One of the characteristics of this epidemic is precisely a very large number of infected and deceased medical workers: so far 160 have been infected and 80 of those died. Below standards ‘Ebola is new in this part of Africa, so the population and health workers don’t know the symptoms of the disease or how to prevent them. Many health workers were scared and didn’t know how to protect themselves from infection. Health systems in these countries were weak at the start of the epidemic and ebola has weakened them even further. It was necessary to close several medical centres to disinfect them properly,’ highlighted a spokesperson for the World Health Organisation in Conakry, Nyka Alexander. The fact that hospitals in west Africa have much lower standards than those we’re used to is testified to by the experience of a doctor from Split, Dr. Marijana Geets-Kesic, who spent almost two years volunteering in a local clinic in Freetown in the early 2000s. ‘It’s hard to describe: the clinic was under a roof made of sheet metal without windows and there were animals walking through it. The hospital had some beds, but only some patients lay in them. Others lay on the floor. Most of these people were so poor that they had never slept on a bed before,’ remembers Marijana Geets-Kesic. ‘Women were giving birth while chickens walked around them. Malaria and AIDS were a daily occurrence. Every day I had at least one or two patients infected with HIV. There was no ultrasound or MRI in the hospital and it was unsafe because of the rebels. Despite all of that, it was a big challenge for me to help these people,’ added M. Geets-Kesic. Given that the epidemic hasn’t been brought under control even after 6 months, the WHO has proclaimed ebola an international threat. They have introduced a series of measures, amongst which is a recommendation to stop air traffic to and from affected countries. Neighbouring countries introduced special measures says Marko Skreb, former governor of the National Bank who now works in Ghana as an official with the International Monetary Fund. ‘Ghana has introduced quite a few measures, although it still doesn’t have any cases of ebola. Among these measures is a ban on any international conferences or gatherings in the next three months. Several isolation centres have been set up and at the airport in Accra there are sanitary staff who look over people who come in with symptoms,’ says Skreb. ‘They’ve especially insured all doctors and medical nurses and limited travel to the affected countries. In the public institutions, including my office, there are educational posters about ebola and hand disinfection units. Also, the media constantly transmit instructions on how to prevent infection,’ added Skreb. Plan for ebola While around the world there have been increased precautions to prevent the infection spreading, in the affected countries there are superhuman efforts to control the deadly virus. ‘For us the challenge now is to discover every new suspected case and all of its contacts and to follow them for 21 days to ensure medical attention as soon as the person gets sick,’ says Nyka Alexander. Meanwhile, Croatian Brigadier Predrag Mikolic together with thousands of other members of the UN who are taking care of peace and safety in Liberia are trying to help the local population to control the dangerous disease. ‘People in Liberia are uninformed and uneducated and often follow traditions that only aid the spread of infection.’ And Dr Linda Rahal and her colleagues are also trying to educate people so that they don’t hide symptoms of ebola because of a fear of being stigmatised. ‘Our country has a plan for ebola that were are trying to implement now. One of the strategies is isolating suspected cases and when they are confirmed, putting them into medical centres. In Sierra Leone, even some villages are in quarantine to prevent the spread of the disease and their citizens are given food and necessary medicines,’ says L. Rahal. ‘But we need help from the WHO and Doctors Without Borders because we have a problem with human potential and the capacity of our medical institutions,’ highlighted L. Rahal. ‘The duration of the epidemic will depend on how people react to information about ebola and on the amount of help we get in fighting this infection. If we get the help, and if our people follow the prevention measures, we could end this epidemic in a few months’ time, that is, by the end of this year,’ concludes Linda Rahal. Ten facts to know about ebola 1) What is ebola? It is an infectious tropical disease considered by Doctors Without Borders to be one of the deadliest diseases in the world. 2) What causes the disease? The cause is the epinomious virus, named after the river Ebola in the Democratic Republic of Congo where the disease first appeared in 1976. 3) How is the disease spread? Ebola is not spread by air, but through direct contact with the bodily fluids of an affected person, such as blood, saliva, feces and sperm. 4) Who is at greatest risk of infection? The greatest risk of infection is faced by family members of infected people, those who are in contact with the bodies of the deceased, and those who take care of infected people including medical workers who do not wear protective gear. 5) What is the incubation period? From 2 to 21 days. During this period, if the patient is infected but has no symptoms of the disease, there is no secretion of the virus and so these patients are not infectious. 6) What are the symptoms of ebola? The early symptoms ressemble flu, and include weakness, muscle pain, headache, high temperature, and cough. Some patients get a rash, hiccups, chest pain, heavy breathing and swallowing, and their eyes become red. As the disease develops, there is vomiting, diarrhoea, internal and external bleeding, and kidney and liver failure. 7) What is the source of the ebola virus? The origin of the virus is not fully understood, but it probably comes from the natural reservoir of fruit bats. So far, ebola cases have come from contact with blood, organs or other bodily fluids of infected chimpanzees, gorillas, fruit bats, forest antelopes and other species. 8) How many types of ebola virus are there? There are five types of the virus, the deadliest of which is the Zaire strain that first appeared in 1976. The cause of this epidemic is a strain very similar to the Zaire strain. At the beginning of this epidemic in March and April, the mortality rate was very high, but it has now stabilised at 64%. 9) Are there any vaccines or medicines against ebola? So far, there are no registered vaccines or medicines against ebola, although a certain number of products is in development. 10) How do you fight ebola? The only available measures that work are preventative, aiming to stop further transmission of the virus from one person to another. This includes isolating infected and diseased people, using protective suits and gear, washing and disinfecting hands, properly dealing with the deceased, keeping an aseptic environment in the areas where patients are being treated, etc. [Pictures of ebola funerals in west Africa, a map of west Africa showing affected areas]