Ivanov_Dodykhudoeva_Sociolinguistic_features_of_Gilaki_an

advertisement

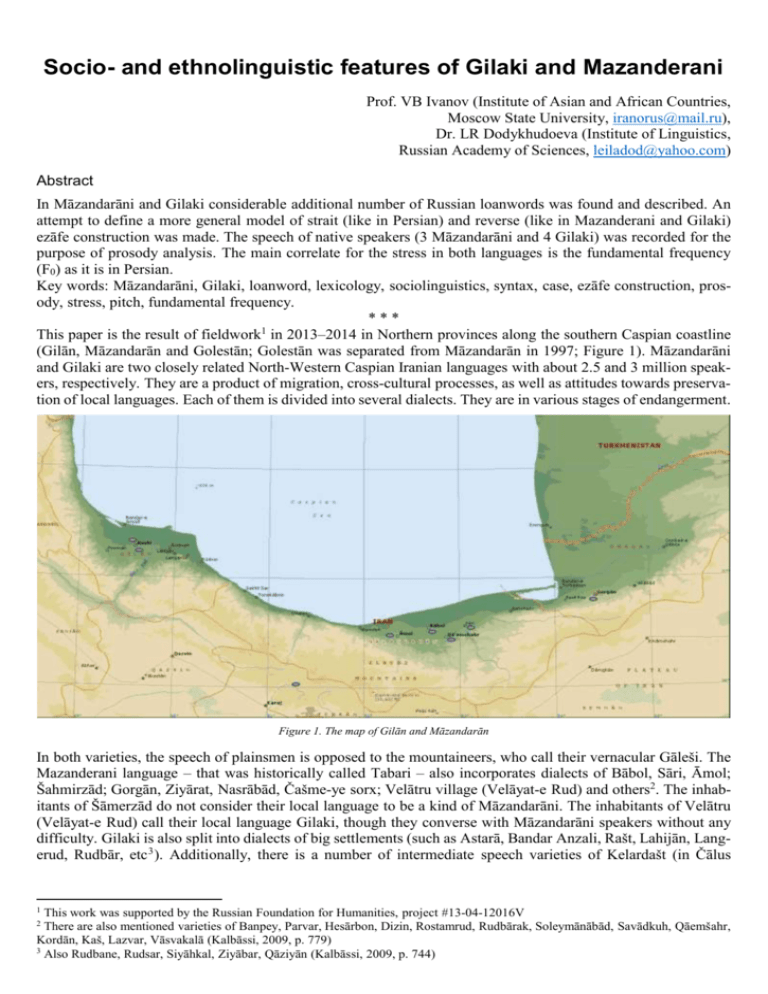

Socio- and ethnolinguistic features of Gilaki and Mazanderani Prof. VB Ivanov (Institute of Asian and African Countries, Moscow State University, iranorus@mail.ru), Dr. LR Dodykhudoeva (Institute of Linguistics, Russian Academy of Sciences, leiladod@yahoo.com) Abstract In Māzandarāni and Gilaki considerable additional number of Russian loanwords was found and described. An attempt to define a more general model of strait (like in Persian) and reverse (like in Mazanderani and Gilaki) ezāfe construction was made. The speech of native speakers (3 Māzandarāni and 4 Gilaki) was recorded for the purpose of prosody analysis. The main correlate for the stress in both languages is the fundamental frequency (F0) as it is in Persian. Key words: Māzandarāni, Gilaki, loanword, lexicology, sociolinguistics, syntax, case, ezāfe construction, prosody, stress, pitch, fundamental frequency. *** This paper is the result of fieldwork1 in 2013–2014 in Northern provinces along the southern Caspian coastline (Gilān, Māzandarān and Golestān; Golestān was separated from Māzandarān in 1997; Figure 1). Māzandarāni and Gilaki are two closely related North-Western Caspian Iranian languages with about 2.5 and 3 million speakers, respectively. They are a product of migration, cross-cultural processes, as well as attitudes towards preservation of local languages. Each of them is divided into several dialects. They are in various stages of endangerment. Figure 1. The map of Gilān and Māzandarān In both varieties, the speech of plainsmen is opposed to the mountaineers, who call their vernacular Gāleši. The Mazanderani language – that was historically called Tabari – also incorporates dialects of Bābol, Sāri, Āmol; Šahmirzād; Gorgān, Ziyārat, Nasrābād, Čašme-ye sorx; Velātru village (Velāyat-e Rud) and others2. The inhabitants of Šāmerzād do not consider their local language to be a kind of Māzandarāni. The inhabitants of Velātru (Velāyat-e Rud) call their local language Gilaki, though they converse with Māzandarāni speakers without any difficulty. Gilaki is also split into dialects of big settlements (such as Astarā, Bandar Anzali, Rašt, Lahijān, Langerud, Rudbār, etc 3 ). Additionally, there is a number of intermediate speech varieties of Kelardašt (in Čālus 1 This work was supported by the Russian Foundation for Humanities, project #13-04-12016V There are also mentioned varieties of Banpey, Parvar, Hesārbon, Dizin, Rostamrud, Rudbārak, Soleymānābād, Savādkuh, Qāemšahr, Kordān, Kaš, Lazvar, Vāsvakalā (Kalbāssi, 2009, p. 779) 3 Also Rudbane, Rudsar, Siyāhkal, Ziyābar, Qāziyān (Kalbāssi, 2009, p. 744) 2 County), and Tonekābon (County); administratively both are included in the territory of Mazandaran province. The places we have taken interviews from the native speakers are marked by blue ellipses (Figure 1, Figure 2). In addition to other similar features, both languages are characterized by: 1. Strong influence of Persian at all levels (phonetics, morphology, syntax, vocabulary). 2. Considerable number of Russian borrowings (a higher number in vocabulary, and more frequent in usage, than in modern Persian). 3. Reverse Status construction (in terms of the sequence of elements), i.e. (ezāfe construction), which unlike Persian begins with a marked dependent determiner followed by the head noun. 4. Pitch accent. Figure 2. Location of Velayat-e Rud Russian loanwords The following material refers to Māzandarāni (see article of Mohanna Rezai, who also took part in our research (Сейед Агаи Резаи, 2013)). These borrowings cannot be found in Persian and are specific for Māzandarāni: آفتکāftek drugstore سیبلوکهsibluke stellate sturgeon بولکهbulkә sturgeon سیچاسsičās deal بتbot skittle سولودکاsoludkā herring بتکهbotkә shack سمشکهsәmәškә pip, seed بدرهbedәrә bucket اسپشکهәspeškә match قاالچqālač white loaf اسدلosdol chair, seat کلشkaloš/ گالشgālәš rubbers تورکاturkā cezve, ibrik (coffee pot with a long handle لوسمانlusmān pilot and no lid) مناتmәnāt coin ختکاxotkā duck ناسوزnāsuz pump خوالینسکم مورهXәvālinskom-more Caspian sea نتکهnotkә thread چرنلčәrnel ink آبشکهābәškә small window شرفšarf scarf آستراāstrā sturgeon شتšot brush پابلوسpāblus mouthpiece cigarette چکاčekā pike, jackfish رزینrezin gum, rubber یاشیگyāšig box سپیستاکsәpistāk whistle Ezāfe construction and the case problem In the proceedings of well-known Russian iranianists (A. Arends 1941, L. Peysikov 1959, Yu. Rubinchik 2001) harmonious system of Persian syntax description from the level of word collocations to the level of complex sentences has been developed. With some reservations this description can be applied to other Iranian languages and their dialects. More elementary syntax level - links between clitics and connective parts of speech (subsyntax) - was not developed at all. One of the aims of this article is to draw attention to it to fulfill this gap and to revise those parts of the syntax theory that are responsible for the interface between subsyntax and more higher levels the syntax of collocations and sentences. Our iranianists postulate 3 cases for Māzandarāni and Gilaki languages (Kerimova et al, 1980, Rastorgueva et al. 1971, Rastorgueva and Edelman 1982, Rastorgueva 1999 I, Rastorgueva 1999 II): Nominative, Genitive and Accusative/Dative. Each of them has its own marker. After closer examination, we notice that the Genitive in many respects differs from the Genitives that can be found in other Indo-European languages. On the one hand, the so called Genitive case marker -ә is used to form pure possessive relations, like: Gil. mi zakanә4 ahvål xob nubu my children’s health was not good; Gil. åhuyә čuman gazelle’s eyes Maz5. pərә xәnә father’s house, Maz. mә bәrarә pәr my brother’s father. That supports the point for being “good” Genitive case marker. But on the other hand the same marker can also be found in Maz.: a) qašəngә kijā beautiful girl, qәrmezә māhi red fish, keškә vačә small child, where it forms attributive collocations (adjective has no case in Māzandarāni and Gilaki, there is no agreement between noun and adjective, so it is no case marker here); b) mә xāxerә-vesse for/to my sister, amә šahrhahә-dәlә in our towns, where the marker joins a noun to a postposition, i.e. forms a subcollocation (so it is no case marker here either). Typological comparison of Mazandaranian and Gilaki vs. Persian can be maintained more correctly in the terms of ezāfe-, head- and dependant-marking (see also (Samvelian, 2008)) and globally the marker of congruence (coupling). All three instances in Caspian languages: 1) possessive relation; 2) attributive relation; 3) postposition link can be combined into a single case - ezāfe case or dependant marking. At the same time in Persian and other Southwestern languages (Dari, Tajik) similar marker is head marking (see also Ivanov 2014): Maz. qašəngә kijā vs. Pers. doxtar-e qašang beautiful girl. Generally, our iranianists avoid indicating the status of the case and ezāfe markers. If we apply to them the property of separability, we see that they are inseparable from the stem. Thus, in both groups of languages the ezāfe markers are endings (flexions). The other case - Accusative/Dative - has the marker Gil. -re/-a, Maz -rә ← *-rā̆ and according to the same authors can mark/indicate (Rastorgueva, Edelman 1982, p. 546): a) addressee: Gil. An-әm bәgәm šume-re Should I tell you, b) appropriation: Gil. Tu tani ame-re utāq peydā bokoni? Can you find me a room? c) purpose: Gil. Huseyn zud bәtanәstә xušanә huquqa bәdanә vә ušanә fagiftәnә-re mubarәzә bokonә Hossein could quickly realize his rights and fight for their fulfillment, d) reason: Gil. Zirābә-re xeyli alamšәnge rā dәgadidi Because of Zirāb much noise was started. If we look closer, we assume that instead of all four function we can introduce only one syntactic role - beneficiant. In Persian the same postposition can be separated from the noun by adjectives and other words: Pers. doxtar-e qašang-rā vs. Maz. qašəngә kijā-rә a beautiful girl (+Akk.). In Māzandarāni and Gilaki we cannot separate the postposition -re from the noun because there is the reverse word order and the ezāfe construction always ends with a noun. Thus, the postposition -re in Māzandarāni and Gilaki can be considered an ending (flexion, part of a word), while in Persian it is a separate word (functional part of speech). There is a lot of other postpositions in Māzandarāni and Gilaki (Rastorgueva, Edelman 1982, p. 546-549), but only postposition -re is said to be as much grammaticized as to be able to form a case. The reason for such a peculiarity is explained by different historical paths of development. But we can also notice the different morphology of the postpositions’ attachment to the stem of the nominal part of speech: the postposition -re is attached directly to the stem, but The other postpositions seem to be used the same way as the postposition -re: Maz. -vәssә for: Intā kār-rә mә-vәssә hākәrdә He did it for me. Maz. -jā from: Mәn tә-jā batәrsimә I was scared by you. Gil. -jir under: Mizә-jir kāqәzana pәxš kudi He threw the papers under the table. Gil. -bija near: Ita duxtar-beče dәrә-bija bāzi kudi This little girl was playing near the door. 4 5 Bold characters show stressed vowels within a word. Otherwise, the words have final stress. Mazandaranian examples are transcribed in Babol pronunciation. Either we invent a case for each of the postpositions, or we must explain the criterion for distinguishing the peculiar postpositions from the ordinary ones. One of the possibilities to distinguish them is to take into consideration the flexion of the ezafe case. The postposition -re joins the stem without it, while the others tend to need the flexion. Vowels and pitch accent The duration of the Māzandarāni and Gilaki vowel system was studied by V. Zavialova in 1956. Vowel [ә] was usually shorter than the others. Māzandarāni vowel system in Rastorgueva, Edelman 1982 p. 465 and Rastorgueva 1999 p. 126 is shown to be asymmetrical (Figure 3 a). Usually in world languages asymmetrical vowel systems are unstable and thus rare. We have found no vowel [ɛ] in Māzandarāni, but instead slightly labialized vowels [ә] and [ā] were discovered. With those corrections, the Māzandarāni vowel system acquires natural symmetrical form (Figure 3 b). Besides, in our recordings we encountered cerebral (retroflex) pronunciation of sonorants (like ṛ, ṇ) that was not mentioned in previous descriptions. Figure 3. Māzandarāni vowels according to Rastorgueva (1999) (a), Māzandarāni vowels revised (b), Gilaki vowels (c) After our corrections made the Māzandarāni vowel system (Figure 3 b) becomes very similar to the Gilaki one (Figure 3 c). The only difference is the presence of relic long vowels [ī] and [ū] in Māzandarāni that was mentioned in Rastorgueva, Edelman 1982 p. 456 and Rastorgueva 1999 p. 114. In order to analyze the acoustic properties of the stress, the speech of native speakers (3 Māzandarāni and 4 Gilaki) was recorded. Segmentation and further analysis was done using Praat (www.praat.org). A sample segmentation with a textgrid is shown on Figure 4. Candidate parameters that usually affect the prosody were extracted from the vowels (the syllable bearers) of the recorded words: a) Scalar: Duration (in msec), F0 (mean fundamental frequency), Imean (mean intensity), Jitter (average absolute difference between consecutive periods, divided by the average period), Shimmer (average absolute difference between the amplitudes of the consecutive periods, divided by the average amplitude), Harmonicity (harmonics-to-noise ratio), b) Integral 2-dimensional (2D): F0area (area under the F0 curve; Figure 5 a), Iarea (area under the intensity curve; Figure 5 b.); c) Integral 3-dimensional (3D): Volume (volume of the 3D-figure made by F0 and intensity curves; Figure 5 c). Multivariate ANOVA analysis done by SPSS showed that the defining feature of the stressed syllables in both languages is pitch (p<0.001). Therefore, we may call this type of word stress tonal. Mazanderani stress has no other significant factors, while in Gilaki intensity (p=0.006) and complex 3D-factor (pitch-intensity-duration) (p=0.034) are also very important. Thus, the stress in Gilaki is complex: tonal-dynamic. The main reason for the common basis of the stress (pitch) could be that the speakers of both languages are bilingual, and Persian, being common for them, has pitch accent. More detailed description of the experiment can be found in (Ivanov, 2014) and (Ivanov, 2015). Figure 4. Segmentation of the Gilaki sentence Ti avāl četo? How are you? Figure 5. Integral parameters of a vowel, 2-dimensional: F0area (a) and Iarea (b), 3-dimensional Volume (c) The extracted parameters were arranged in tables. Then absolute parameters were transformed into relative ones. The value of the parameter in the accented syllable was assumed to equal to 100% (Table 1). Table 1. A sample of relative parameters of the syllables pronounced by Gilaki speakers Sāsān and Hamid Duration Dialect Gender Name Vowel Word Meaning Gilaki m Sāsān a salām hi salām avāl avāl % % % % 1 0 42 91 34 95 27 36 1 100 100 100 100 100 100 0 43 94 35 94 41 40 1 100 100 100 100 100 100 0 151 88 88 96 162 91 1 100 100 100 100 100 100 0 165 92 152 97 193 146 1 100 100 100 100 100 100 0 36 114 57 103 32 61 1 100 100 100 100 100 100 0 71 127 93 110 79 103 1 100 100 100 100 100 100 1 100 100 100 100 100 100 1 2 ā o koni (you) do 1 i o koni 2 i e nemә no 1 šimi your 1 ә i i Volume % ā a Iarea % 2 condition Imean Stress ā a F0area Try ā a F0 0 64 74 46 83 55 39 1 100 100 100 100 100 100 0 105 107 143 102 102 121 Duration a a zakan children 1 F0 F0area Imean Iarea Volume 0 69 87 50 99 66 59 1 100 100 100 100 100 100 Glossing of a Mazandaranian story with Persian translation (author T. Yazdān Panāh Lamuki) Attā pīte bīy-e attā šexpespǝlik attā hessekā One log PSTStem.be-PST.3Sg one wren one bone Kande-i xošk-e puside bud, yek-i elikāyi va yek ostoxān. Attā zemessun ruz bīy-e vūrd-enǝ attā xǝne-i delǝ One winter day PSTStem.be-PST.3Sg PSTStem.go-PST.3Pl one house-Art in Ruz-e zemestāni bud, raftand dāxel-e yek xāne. Šexpespǝlik būrd-ǝ kǝle pǝšt henīšt-e Wren PSTStem.go-PST.3Sg fireplace behind PSTStem.sit-PST.3Sg Elikāyi raft bālā pošt-e ojāq nešast. Hessekā būrd-ǝ bālā kǝle sī Bone PSTStem.go-PST.3Sg top room in Ostoxān dar sadr-e očāq. Pīte miyun-e kǝle sī henīšte Log between-Izf room in sit.PST.3Sg Kande-ye xošk vasat nešast. Kǝle per-e taš bīye Fireplace full-Izf fire be.PST.3Sg Ojāq por'āteš bud. Šexpespǝlik hamintī_ke čort zue kafǝne kǝle delǝ Wren as_soon_as drowsiness beat.PST.3Sg fall.PST.3Sg fireplace in Elikāyi hamin-ke raft čort bezane, oftād dar ojāq-e āteš. Pītǝ būrd-e šexpespǝlik-ǝ nejā dāde vere taš kafǝn-e Log PSTStem.go-PST.3Sg wren-Akk saving PSTStem.give.PST.PCPT go.PST.3Sg fire PSTStem.catch-PSЕ.3Sg Kande-ye xošk raft elikāyi-rā begirad, āteš oftād be jān-aš. Hessekā ke badiy-ǝ hamǝ-rǝ taš dakǝt-e Bone as_soon_as PSTStem.see-.PST.3Sg all-Akk fire PSTStem.take-PST.3Sg Ostoxān ke did hame-rā āteš oftād, Būrd-ǝ barīm mardem xaver hākǝnǝ PSTStem.go-PST.3Sg outside people news PRSStem.do-SUBJV.PRS.3Sg Raft birun mardom-rā xabar konad. Sag en-ǝ ver-e vayn-e Dog it-Akk PSTStem.go-PST.3Sg PSTStem.take_away-PST.3Sg Sag āmad u-rā bord. Miscellaneous We have detected some discrepancies with the generally accepted description of Mazanderani, especially in the field of phonetics. Although nowadays Mazanderani has no written presence, some books in Arabic script with Latin transcription (dictionaries, collections of proverbs and sayings, legends and narratives) can be found. The actual pronunciation and phonemic composition of some words differ, first, from their presentation in traditional literature, and, secondly, from the manner linguistically educated native speakers write themselves. Well-educated Gilaki speakers use Persian alphabet to write books and articles. A well-known Gilaki writer M.P. Jektaji publishes the literary journal Gilavā. Here, a special superscript letter (7) is used to denote the vowel [ә] (ezafe) in the texts. A corpus of texts on these speech varieties was compiled, and can be accessed on the site of the Institute of Linguistics of the Russian Academy of Sciences. The database is given for these language varieties in audio- and written transcription (in Iranian and IPA variants), Russian translation. For the Gilaki language, we also provide the audio recording of texts from V.S. Rastorgueva et al (1971) (http://iling-ran.ru/iranistika/4tmp/). Comparing the speech of our language consultants with this book, we have found out that the vocalism in the book tends towards Tajiki. For instance, there is written the expression Či kuni? “What are you doing?” (text 1). Our consultants pronounce it Če koni? In many other texts we see the same kind of substitution (e↔i, o↔u). Thus, the phonetic description of Gilaki requires further work and refining. For the Mazandarani language, we offer recordings of the Mazandarani proverbs and parables (Yazdān Panāh Lamuki 1997 6771 ، ;یزدانپناه لموکیAnsari 2011 6731 ،انصاری, as well as some narratives on the lifestyle history and cultural traditions of the people taken during our fieldwork. In general, Māzandarāni and Gilaki speakers can understand each other, though customarily they communicate in Persian. From a sociolinguistic point of view, Māzandarāni is not treated as a prestigious language. Unacquainted people in the streets usually address each other in Persian and change to their local language only after they get acquainted. For instance, a local passer-by would buy a newspaper from a local newspaper seller, using Persian. Even a local woman would discuss her divorce suit with a local attorney exclusively in Persian. Parents, especially in rural communities, encourage their children to speak Persian always, in order to make their speech undistinguishable from that of residents in the capital. They do this so that their children can seek a better career in Tehran. This striving for a better life and higher social status is one of the reasons why the social basis for Caspian languages is shrinking. Our native speakers References Ansāri, M, Dictionary of Mazandarani proverbs, 2011 ، شااال ین، سااااری.انصااااری مسااا ی فرهنگ زربالمثلهای مازندرانی .661-6 . ص.6731 ISBN 978-964-2731-21-3. Arends AK. Brief syntax of the literary contemporary Persian. Арендс А.К. Краткий синтаксис современного персидского литературного языка. Moscow-Liningrad. Академия наук СССР, Институт востоковедения. Proceedings, 1941. V. XLII, pp. 1-189. Ivanov, VB. Gilaki prosody. Иванов В. Б. Гилякская просодия // Ломоносовские чтения. Востоковедение. Тезисы докладов научной конференции. Moscow: Moscow State University, April 2015, pp. 86-87. ISBN 978-5-19-011059-3. Ivanov, VB. Mazandaranian prosody. Иванов В. Б. Мазандеранская просодия // Ломоносовские чтения. Востоковедение. Тезисы докладов научной конференции. Moscow: Kluch-S, 2014. pp. 103-105. ISBN 9785-906751-02-7. Ivanov, VB. To the classification of nominal forms in Southwestern Iranian languages. К классификации именных форм в юго-западных иранских языках // Вопросы языкознания. Москва, №2, 2014 Kalbassi, I. A Descriptive Dictionary of Linguistic Varieties in Iran. Institute for Humanities and Cultural Studies, Tehran, 2009. 6711 ، تهران،پژوهشگاه علوم انسانی و م العات فرهنگی. فرهنگ توصی ی گونههای زبانی ایران،کلباسی ایران Kerimova AA., Mamedzade AK, Rastorgueva VS. The Gilaki-Russian dictionary. Керимова А.А., Мамедзаде А.К. и Расторгуева В.С. Гилянско-русский словарь Moscow, Nauka, 1980, pp. 1-467 Peysikov LS. The issues of the Persian syntax. Пейсиков Л.С. Вопросы синтаксиса персидского языка. Moscow, IMO, 1959, pp. 1-411. Rastorgueva VS. Mazandaranian language. Расторгуева В. С. Мазандеранский язык // Языки мира. Иранские языки. II. Северо-западные иранские языки. Moscow: Indrik, 1999. V. II. 3. ISBN 5-85759-099-X. Rastorgueva VS. The Gilaki language. Расторгуева В. С. Гилянский язык // Языки мира. Иранские языки. II. Северо-западные иранские языки. Moscow, Indrik, 1999. V. II, 3. ISBN 5-85759-099-X. Rastorgueva VS., Edelman JI. GIlaki, Mazandaranian (with dialects of Shamerzadi and Velatru). Расторгуева ВС. и Эдельман Дж.И. Гилянский, мазандеранский (с диалектами шамерзади и велатру) // Основы иранского языкознания. Новоиранские языки: западная группа, прикаспийские языки. Moscow: Nauka, 1982. V. 3. VIII. Rastorgueva VS., Kerimova AA., Mamedzade AK., Pireyko LA., Edelman JI., Gilaki Language (1971). Расторгуева В. С. и др. Гилянский язык Moscow, Nauka, 1971, pp. 1-321. Rezāi, M. The evolution of Russian loanwords in Mazandaranian. Сейед Агаи Резаи М. Эволюция русских заимствований в мазандеранском языке // Фундаментальные исследования. October 2013, pp. 3011-3015. ISSN 1812-7339. Rubinchik YuA. The grammar of the contemporary literary Persian. Рубинчик Ю. А. Грамматика современного персидского литературного языка. Moscow, Vostochnaya literatura RAN, 2001. pp. 1-600. ISBN 5-02-018177-3. Samvelian P. The Ezafe as a head-marking inflectional affix: Evidence from Persian and Kurmanji Kurdish // Aspects of Iranian Linguistics: Papers in Honor of Mohammad Reza Bateni Cambridge Scholars ltd, 2008, pp. 339-361. Yazdān Panah Lamuki, T., Dictionary of Mazandarani proverbs, 1996. یزدان پنااااه لموکی یاااار فرهناااگ مثلهاااای .721-6 . ص.)6337( 6771 ، فرزین،تهران. مازندرانیISBN 964-90006-8-2. Zavialova VI. New information on Iranian languages phonetics. Gilaki and Mazandaranian languages. Завьялова В.И. Новые сведения по фонетике иранских языков. Гилянский и мазандеранский языки. // Труды ИЯз. Москва, 1956. V. VI.