Japanese-American Internment

During World War II about 117,000 people of Japanese ancestry

living in the United States were interned (confined). They were

taken from their homes. Then they were held in wartime

concentration camps. These camps were called "relocation

centers." This was the largest single forced relocation in U.S.

history. America's entry into the war followed Japan's attack on

Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on December 7, 1941.

Almost two-thirds of those interned were American citizens. They

were interned from 1942 until the end of World War II in the

Pacific, in 1945. In 1988 the U.S. government apologized to the

Japanese Americans. Their forced internment, the government

admitted, was based on "race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure

of government leadership."

The Reasons for Internment

There were anti-Japanese feelings in the United States long before

Pearl Harbor. These feelings were especially strong in California.

A majority of Japanese immigrants to the continental United States

had settled there. Many of them had found success in farming.

The Japanese attack fueled even greater hostility. People believed

that Japan would now attack the U.S. mainland. And they feared

that Japanese Americans would work against the American war

effort.

Japanese Americans

According to the 1940 U.S. census, almost 285,000 people of

Japanese ancestry lived in the United States. About 158,000 were

in Hawaii, which was then a U.S. territory. The other 127,000 lived

in the continental United States. About 75 percent of those were in

California. Washington and Oregon accounted for another 14

percent.

There were no plans to intern Japanese Americans living in

Hawaii. Nor were there plans to intern Japanese Americans living

east of the Sierra Nevada mountains. Only those living on the West

Coast were interned. But they accounted for 89 percent of Japanese

Americans living in the continental United States. The Canadian

government adopted a similar policy in the province of British

Columbia.

The Internment Camps

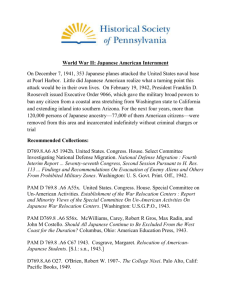

President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 in

February 1942. It established a Pacific military zone. All persons

of Japanese ancestry had to leave that zone. The government gave

two reasons for this. The first was to prevent spying. The second

was to protect people of Japanese descent from harm at the hands

of Americans.

Roosevelt signed another executive order in March. It created the

War Relocation Authority (WRA). The WRA soon built ten

relocation camps. Within weeks, people of Japanese ancestry were

ordered to assembly centers near their homes. They were then sent

to WRA relocation centers. These centers were situated many

miles inland. Often they were in remote and desolate areas. Sites

included Minidoka, Idaho; Manzanar, California; Topaz, Utah;

Jerome, Arkansas; Rohwer, Arkansas; Heart Mountain, Wyoming;

Gila River, Arizona; Poston, Arizona; and Granada, Colorado.

Troublesome people were sent to a special camp at Tule Lake,

California.

The internees lived in buildings made of wood and tar paper. There

were schools, libraries, hospitals, and post offices. People slept on

army cots and kept warm with coal-fired potbellied stoves. Many

made their own furniture from scrap wood. There were also guard

towers. The camps were guarded by military police.

The WRA camps were the largest and best known. The

Immigration and Naturalization Service and other agencies ran

other camps.

The End of Internment

The camps were closed after World War II ended in the Pacific in

September 1945. Many Japanese Americans returned to their home

states. Others found new places to live.

During World War II, more than 20,000 Japanese Americans had

served in the U.S. Army. Many, such as those of the 442nd

Regimental Combat Team, had fought bravely in Europe. Others

had been in U.S. military intelligence in the Pacific. Americans

soon realized that a terrible thing had been done to loyal American

citizens.

After the war, some Japanese Americans received compensation

for property losses. Their losses were estimated at more than $400

million. But Congress appropriated only $38 million to settle all

claims. Much later, Congress passed a special bill. It awarded each

of the surviving internees $20,000 in 1988. The bill also

apologized for the internment of the Japanese Americans.

Two of the internment camps are now National Historic Sites.

They are Manzanar in California and Minidoka in Idaho. The

Nidoto Nai Yoni Memorial on Bainbridge Island, Washington, is

part of the Minidoka National Historic Site. The Japanese

Americans who lived on Bainbridge Island were the first to be

forced to leave their homes. Nidoto Nai Yoni is Japanese for "Let it

not happen again."

Among the Japanese American internees who later rose to

prominence was Norman Mineta. He served in the cabinets of

Presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush. Other notable former

internees include singer-actress Pat Suzuki and actors Pat Morita,

Jack Soo, and George Takei. Today, Japanese Americans form a

thriving community of 1.2 million people.

How to cite this article:

MLA (Modern Language Association) style:

"Japanese-American Internment." The New Book of Knowledge.

Grolier Online, 2013. Web. 5 Feb. 2013.

Chicago Manual of Style:

"Japanese-American Internment." The New Book of Knowledge.

Grolier Online

http://nbk.grolier.com/ncpage?tn=/encyc/article.html&id=1000307

9&

type=0ta (accessed February 5, 2013).

APA (American Psychological Association) style:

Japanese-American Internment. (2013). The New Book of

Knowledge. Retrieved February 5, 2013, from Grolier Online

http://nbk.grolier.com/ncpage?tn=/encyc/article.html&id=1000307

9&

type=0ta

™ & © 2013 Scholastic Inc. All rights reserved.