Buffington Indian Legend

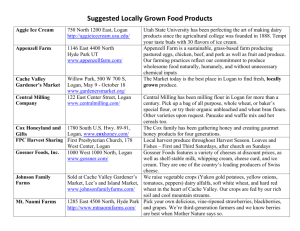

advertisement