BYRNE Philip John and WEAVER Jacqueline

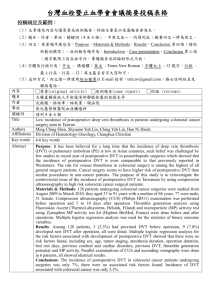

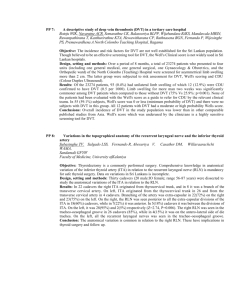

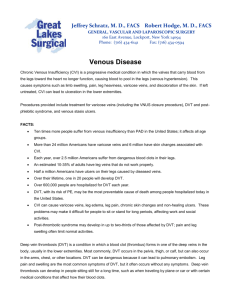

advertisement