Special and spotless? Or maybe not? Language myths in tourism

advertisement

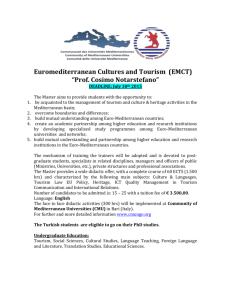

SPECIAL AND SPOTLESS? OR MAYBE NOT? LANGUAGE MYTHS IN TOURISM Višnja KABALIN BORENIĆ Department of Business Foreign Languages Faculty of Economics and Business, University of Zagreb 6 J. F. Kennedy Square, Zagreb, Croatia vkborenic@efzg.hr Sanja MARINOV Department of Foreign Languages and PE Faculty of Economics, University of Split 5 Cvite Fiskovića, Split smarinov@efst.hr Martina MENCER SALLUZZO Department of Languages and Culture Vern – University of Applied Sciences, Zagreb 3 Ban Jelačić Square, Zagreb, Croatia martina.mencer.salluzzo@vern.hr Abstract The aim of this paper is to address two myths related to English as the language of tourism. One is that undergraduate students of tourism, similar to a significant part of Croatian population, believe they have a high level of proficiency in English, and two, that they are with their high level of English, well equipped with the language they need for working in the tourism field. The language of tourism is unique. Although it may not have a well-defined content and clear functional boundaries as it is influenced by a wide range of disciplines (Calvi, 2005), it has specific purposes and should be addressed as such, different from general English. It is structured, it follows certain grammar rules, has a specialised vocabulary and semantic content, and it adopts a special register (Dann, 1996). Furthermore, the language of tourism uses a special register with a corresponding set of genres that are appropriate for particular communication situations within the industry and with and among both tourists and tourees (Dann, 2012). Awareness of the existence of the specific language of tourism and its skilful usage should increase the quality of the tourism product. In order to weigh tourism students’ language skills against their perceptions, attitudes and expectations a written assignment designed to demonstrate students’ language competences has been combined with a specially designed targeted questionnaire. The survey will investigate students' attitudes to and perceptions of the need for improving and refining their language skills (both English and other languages) as part of the undergraduate Tourism courses. Tourism sells and delivers dreams. The industry is characterized by fierce competition, and we believe that a high level of language competence is required in order to reach the ultimate aims of the language of tourism: to persuade, lure, woo and seduce millions of human beings and, in so doing, convert them from potential into actual clients (Dann, 2003:2). Keywords: language of tourism, ESP, tourism students, language attitudes JEL code: A22, A23, L83 1. Introduction At a mythical place, a perfect Destination, tourists would find the dream they came searching for. They would also find a perfect host – a charming, communicative, hospitable local, willing to help, ready to serve, eager to communicate. But what happens when the perfect host does not speak the perfect language, when he derails the impression, spoils a reservation, shakes the image created by perfect semantics; when language full of mistakes wakes our guests up from the mythical dream. Should the world “myth” then be linked with the mythical image, or should we interpret it as a “popular belief” or “false notion.” (http://www.merriam-webster.com). In this paper the latter will be the case: the myth of Croatia as an anglophone country will be analyzed from the perspective of the English-for-specific-purpose teachers and students getting ready for the careers in the tourism field. In globalised economies English is considered a basic skill (Graddol, 2006). Its dominance as a lingua franca in business settings is indisputable (Nickerson, 2005; Čepon, 2005; Klein, 2007); and as many as 79% of Europeans believe English is the most useful language their children should learn for their future (Eurobarometer, 2012). For decades now Croatian educational authorities have promoted learning foreign languages from an early age (Mihaljević Djigunović, in press) and 85-90% of children nowadays learn English from grade one of formal education (Medved Krajnović & Letica, 2009). Upon passing the state high school leaving exam, typically after 9 to 12 years of English instruction, Croatian high-school graduates enter higher education with a lot of self-confidence and a satisfactory command of general English: the levels required by the national curriculum are reached (A2 by the age of 14, and B1 by the age of 18, according to CEFR 2001), but students are better in language reception than in language production (Bagarić 2007; Geld and Stanojević 2007; Josipović Smojver 2007; Medved Krajnović 2007; Zergollern-Miletić 2007). At that point, reasonably proficient and accustomed to using general English for private purposes, most Croatian university students embark on English for special purposes (ESP) courses designed for their professional needs (Kabalin Borenić, 2010a). As inexperienced ESP learners, freshmen university students are seldom aware of the specific nature of the ESP, and when it comes to English of Tourism the misunderstandings appear to be even more widespread. Two myths regarding English and other foreign languages used in the tourism industry will be addressed: 1) In Croatia, most young people these days speak good English, and 2) English of Tourism is just general English used to speak about more specific contents that we are all more or less familiar with because we live in a country with a highly developed tourism industry. Speaking good (general) English is therefore sufficient for handling most jobs in the tourism field. In order to respond to these two myths we have set several more specific goals: Present an overview of the most widely accepted theory of the specific sociolinguistic characteristics of the Language of Tourism. Explore the awareness of the difference between general English and English of Tourism among the students of tourism. Analyze the students' motivation for studying English of Tourism as a specific form of English. Investigate students' perceptions about their proficiency in English: general proficiency, proficiency in each of the four main skills, and proficiency in specific skills studied as part of the language of Tourism curriculum. Compare the students' perceptions with the actual results they achieve. In particular, we will analyze a written assignment and indicate the most frequent types of errors. The results should help create the guidelines for approaching this and similar written assignments in the future. 2. Theoretical background 2.1. English of Tourism Tourism plays a prominent role in modern society. Millions of people are on the move, choosing, using and experiencing countless social and natural phenomena. The language preceding these encounters as well as that deriving from them is necessarily a special kind of language, one capable of fulfilling the manifold communicative goals and needs of the tourism discourse community. According to Swales (1990: 24-27), a discourse community follows the recognized public goals, has a communication mechanism that includes providing information as well as feedback, uses one or more genres, has a specific vocabulary and a perspective of acquiring new membership. All of the above holds true for the tourism discourse community that represents reality using a communicative loop in which verbal representations of the producer respect the expectations of the receiver. The language of tourism reflects social functions fulfilled by tourism: the search for authenticity (MacCannel, 1989 as quoted in Dann, 1996: 7-11), the search for strangehood (Dann, 1996; 12-17), the desire to play (Dann, 1996: 17-23) and the desire to experience the excitement resulting from conflict (Dann, 1996: 25-26). The language of tourism is therefore affected by the need to provide/obtain the desired experiences. For example, the authenticity perspective is reinforced by explicit expressions and the strangeness perspective by words expressing novelty. The language of tourism has four principal properties: functions, structure, tense and magic (Dann, 1996). In order to reinforce the claim that the language of tourism follows a set of special rules we quote a few examples. While the directive function is often reduced to vague imperatives, and the metalinguistic function is underutilized, the expressive function of LoT is fulfilled by replacing "I" with "we" and "our" and the use of value judgments and superlatives. To fulfill its poetic function LoT relies mostly on metaphors and metonyms. As regards the structure of tourism discourse, it aims to capture attention, maintain interest, create desire and get action. The temporal focus of tourism is either in the past or in the future, as this approach allows the tourist to escape from the present. In order to inspire desire the industry touts the 3Rs (romanticism, regression and rebirth), 3H's (happiness, hedonism and heliocentrism), 3F's (fun, fantasy and fairy tales), and 3S's (sea, sex and socialisation). On top of it all, a willing suspension of disbelief on the part of the tourist is crucial in achieving the escape. All of these social functions are reflected in the language of tourism. Furthermore, as the language of tourism implies intercultural communication, a tourism professional should also be aware of the required levels of politeness in intercultural communication and of both universal and country-specific taboos (Mader and Camerer, 2010). And finally, the complex issue of politeness is made even more intricate by the postmodern ethos of trialogue between the key players of tourism: the industry, the tourist and the touree (Dann, 2012), which means that a tourism professional has to master several different genres. Since the English of tourism should be used to "persuade, lure, woo and seduce millions of human beings, and, in so doing, convert them from potential into actual clients" (Dann, 2003:2), the level of language competences can well make the difference between success and failure of a tourism product. 2. 2. Motivation Language attitudes and motivation play a vital role in the language learning process (Mihaljević Djigunović, 1998; Dörnyei, 2005; Gardner, 2010). Motivation determines the amount of energy an individual is ready to put into his/her language learning. The fact that English has become a global lingua franca induced increasing numbers of people to ‘study it as an obvious and selfevident component of education’ (Dörnyei, Csizér & Németh, 2006, p. 89). Consequently, many EFL environments are characterized by the vague, but pressing sense of need to learn English. There is, however, evidence that such vaguely expressed goals fail to support a serious learning effort (Yashima, 2000; Lamb, 2004, Kabalin Borenić, 2013). 3. Study Description 3.1. Participants Altogether 115 first-year students of tourism from the Faculty of Economics, University of Split, took part in the study. The sample was divided into two groups at random: 65 who took part in the survey and 51 who responded to an e-mail booking inquiry. This study design was chosen as we wanted the latter group of participants to be unaware of our research goals. The two groups were comparable in every way and the background information on participants collected by the questionnaire can be taken as representative of the whole sample. More than 80% of the participants were 18- and 19-year olds, and about 85% had had between 9 and 12 years of formal English instruction. The average grade for English at the end of primary school was excellent for 70% and very good for the further 18% of participants. Interestingly, the number of excellent grades in highschool decreased by 25% while there was a 20% increase in very good grades. The average English grades at university level decreased dramatically: only 4.6% of participants had excellent grades, 15.4% had very good grades and there was an equal percentage of good and sufficient grades (27.7%). As regards the situation in which the participants use English skills in their private life or for professional/educational purposes, it was established that the participants used English more frequently for professional or educational purposes, with between 64% and 69% using English often or all the time across the four skills. At the same time, between 35% and 45% of participants used English frequently in private life. The only exception to this rule was listening in private life with 86% of participants using English often or all the time. 3.2. Instrument The data were collected using a four-part questionnaire developed by the authors. The first part of the questionnaire collected the background information (gender, age, year of study, number of years studying English so far, average grades for English during formal education and frequency of English usage in private and professional life). The second part investigated the participants' perception of the differences between GE and LoT (8 Likert statements). Motivation for learning English was briefly investigated in the third part of the questionnaire. The participants were asked to choose only one reason for learning GE among five reasons commonly quoted in the literature: English is a lingua franca (e.g. Lamb, 2004; Yashima, 2000), personal development (e.g. Mihaljević Djigunović, 1998; Dörnyei, 2005), international communication (e.g. Yashima, 2000), and two kinds of instrumental motives (employability - instrumental motivation with future focus, and GE as educational tool - instrumental motivation with present focus; Kabalin Borenić, 2013). Next they evaluated nine Likert statements for the particular motives related to Tourism as an academic subject and Tourism as industry. In the last part of the questionnaire, the participants were asked to assess their language competences and problems (ranking lists of general language skills, specific tourism-related language skills, self-assessing the ability to communicate efficiently in writing / speaking, determining the biggest source of problems in spoken and written communication). 3.3. Writing task – response to an e-mail booking inquiry The participants were asked to reply to an e-mail booking inquiry (a typical task taken from a business correspondence textbook). They attempted the task before receiving any formal instruction on business correspondence. 3.4. Methods The participants completed the questionnaires during regular English for Tourism classes. The data collected were analysed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences. Responding (handwritten) to an e-mail booking inquiry was assigned as a writing task in class. All participants' responses were analysed using content analysis method and AntConc concordancing software. 4. Results analysis 4.1. Perceived differences between GE and EoT The analysis of the participants' perception of the differences between GE and EoT revealed as many as 67.7% of students agree that there is a difference, but there is a lot of disagreement regarding its source: approximately equal numbers agree (35.3%), disagree (35.4%) or stay neutral (29.2%) regarding the claim that the difference between GE and LoT derives from the specific content of tourism. In keeping with the popular perceptions of LSP, as many as 77% of the participants agree that EoT is just GE with specific tourism vocabulary added. Furthermore, 87.5% students believe it is necessary to have a good background in GE before advancing to EoT. Almost half of the students (45.3%) think that studying EoT is more challenging than studying GE, many remain neutral (35.9%) and 18.8% do not see it as a challenge. This result is not contrary to the finding that a good background in GE is a valuable prerequisite (86.2% agree). It may indicate that certain students feel they have the necessary background and are therefore able to respond adequately to the challenge of EoT. Finally, as many as 70.7% of students believe that communicating with tourists and colleagues in the tourism industry requires special communication skills, admitting thus, be it indirectly, there is a difference between EoT and GE. The above results, obtained by simple descriptive analysis, reveal a certain confusion. Even though a significant majority claims that there is a difference between GE and EoT, they cannot determine the nature of the difference and a surprisingly large percentage do not realize that EoT has quite specific goals. The participants, furthermore, seem to be uncertain regarding the important features of EoT: even though 77% agree that lexis only makes EoT what it is, 70.7% believe they will need special English communication skills as tourism professionals. In order to probe these controversies, we looked at the interrelation between the claim that special communicative skills are required and the claim that there is a difference between GE and EoT. The results show that 29 students who see the difference also believe that special skills are needed for communication in tourism. There are, however, 12 students who are neutral about the difference but still agree that special skills are needed. Finally, there are 10 students who are neutral about whether we need special skills for communication in tourism but still see the difference between GE and EoT. 4.2. Student motivation for learning EoT Confronted with the task of picking only the most important motive from a list of five typical motives for learning GE, more than half of students (55.4%) chose the explanation that English has become a lingua franca of modern age. The next most popular reason (18.5%) for learning GE is that it gives advantage in the labor market. Only 10.8% study it because it broadens the mind and opens up new horizons, and 4.6% learn it to communicate with foreigners. Sadly, only 1.5% of our participants (first year undergraduate students) learn it primarily because it is essential for their studies. Although the choice of studying English as a lingua franca sounds a reasonable one, a cause for worry stems from the findings of a recent research study into the motivation of Croatian business students to learn English (Kabalin Borenić, 2013). Instrumental motivation with present focus (English is essential for one's current studies) correlated most strongly with effort invested into learning English. At the same time, the vague claim that English should be learnt because it is a lingua franca had no correlation with the learning effort. Clearly, the correlation results for learning effort and affective factors obtained by Kabalin Borenić make us wish that our participants' ranking list of motives were turned up-side down. The results obtained in the present study are also slightly discouraging for the teachers of EoT who expect the students at this stage of their education to be interested in increasing their employability by developing skills related to their career prospects. We also hope that, as the students progress through their professional courses at the Faculty, more than one student (1.5%) will find English essential for their studies and start reading professional literature and academic articles in English. The curious fact that students do not consider employability issues could be the reflection of the current situation on the labor market where students do not see many realistic opportunities of finding employment. When employability is mentioned directly, however, 95.3% do believe studying EoT can increase their employment competitiveness. This result is not at all in line with the fact that only 33.9% of participants think that studying EoT is more useful for them than studying GE, whereas as many as 35.4% are neutral on this point. The contradiction of this pair of answers is best seen in Table 1 which presents the results of interrelatedness between the two questions. The contradiction is concentrated on the two highest scores in the table. Namely, there are 18 (1 + 12 + 5) students who do not think studying EoT is more useful than GE but they do think studying EoT can help them improve their employment competitiveness. Also, there are 22 (14 + 8) students who do not know if it is more useful for them to study EoT, but they still think it can help them increase their employment competitiveness. Table 1: Interrelatedness between the to variables: I believe studying EoT can help me improve my employment competitiveness / For me it is more useful to study EoT than GE For me it is more useful to study English of Tourism than General English. strongly disagree disagree neutral agree strongly agree Total I believe studying English of Tourism can help me improve my employment competitiveness. strongly neutral agree strongly agree disagree 0 0 1 0 Total 0 1 0 0 1 19 23 18 4 65 2 0 0 0 2 12 14 11 2 40 5 8 7 2 22 1 Source: own research Taking into consideration all students’ responses in this part of the questionnaire, we have to conclude that students persistently favor GE over EoT, even to the point that they think GE, rather than EoT, is more useful for them / can help them improve their position in the tourism labor market. A weak interest in LSP has been recorded in other Croatian studies as well (Mihaljević Djigunović, 1998; Mihaljević Djigunović, 2007; Kabalin Borenić, 2010b). Finally, this particular sample of students is not very motivated by discussing tourism related topics. Almost half of the students gave a neutral answer (49.2%) and 11 students (16.9%) are not motivated at all. These results come as a great surprise but are related to and supported by other results from this study. The participants’ lack of interest is in contrast to the teachers’ effort to motivate students by linguistic activities that are related to their actual needs (Tribble, 1997) and to help them understand the actual relationship between the subject of their studies and the language use (Donna, 2000). Even though EoT is not very motivationally effective, the participants seem to appreciate some of the content taught in EoT courses. Namely, the students think that the course has helped them acquire tourism related contents of direct relevance to their study program (60%) as well as to their future employment possibilities (73.9%). The slight advantage of the latter could be due to the fact the course itself emphasizes more professional and less academic contents, but also the fact the students are still in the first year and other modules they are taking are still focused on acquiring some general knowledge of economics rather than on specific tourism contents. 4.3. Self-assessed language competences and problems The third specific issue we are investigating in this study is students' perception of their proficiency in English. When assessing their own general proficiency in English the students are rather confident about their knowledge. More than half (52.4%) think they are sufficiently proficient and only 4.6% (three students) do not think so. All the rest (43.1%) are neutral. Overconfidence about their language skills is a commonplace among the Croatian learners of English and probably presents one of the main obstacles in acquiring knowledge and language skills (Kabalin Borenić, 2013). It may have resulted from a long record of formal language learning and from the fact they can manage with their English in common everyday situations. To support this view we can quote a comparative study of Croatian and Hungarian learners of English at age 14: Croats performed significantly better in communicative tests, with significant differences in overall scores and listening and reading comprehension (Mihaljević Djigunović et al., 2008). Moreover, overconfidence may have resulted from high exposure to spoken English (films, music). Research on such exposure has shown evidence of its effect on incidental learning of English (Mihaljević Djigunović and Geld 2002/2003). The question is: Can this be enough for a tourism professional with an academic degree? Table 2 shows how students assess themselves when the four specific language skills are considered separately. On a scale from 1 to 4, number 1 stands for the best developed skill and 4 for the worst. Therefore, the lower the mean the better the skill. Accordingly, students see speaking as their main strength, followed closely by reading and listening. Writing is positioned far behind listening, and we can say it is seen as the major weakness. Table 2: Students' perception of their proficiency in the four language skills Statement Mean My proficiency in speaking compared to the other three skills (on the scale 1- 4). 2,1385 My proficiency in writing compared to the other three skills (on the scale 1-4). 3,2154 My proficiency in listening compared to the other three skills (on the scale 1-4). 2,4154 My proficiency in reading compared to the other three skills (on the scale 1-4). 2,2308 Source: own research As language instructors with a lot of classroom experience we do not share this perception of skills distribution (Kabalin Borenić, 2010a). Namely, we believe that ranking speaking so high is the students' overstatement of their speaking abilities. It is not likely productive skills (speaking and writing) will be better developed than their receptive skills (reading and listening). The overstatement may result from a lot of exposure to spoken English which deceives students into believing that if they understand a language well they can also speak it well. This assumption has been confirmed during recent focus group interviews with business students (Kabalin Borenić, 2013). Another reason may be that writing is practiced less in the formal language education. It takes time for the students to write the text and teachers to assess the written work, so it is often avoided. Speaking is also seen as more useful. 76.6% of students enrolled into English for Specific Purposes course at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciencies are most interested in spoken communication on current issues of relevance to younger people (Jelovčić, 2008). These results only confirm the fear that students prefer conversational classes because they feel they do not need to be very precise in their language choices and they will still be understood. They also think they do not have to fit into a strict form but their speech can be loose. However, if we consider the spoken forms such as presentations, meetings, negotiations, telephone bookings, or responding to face-to-face complaints it becomes quite obvious that speaking is also rule driven and these rules have to be learnt and followed. The answers students provided for two of the questionnaire items concerning the difficulties they encounter in speaking or writing only support the theory that speaking and writing are not two such different skills and it takes time and practice to master them both. As Table 3 shows the students were asked to identify which of the four difficulties present a bigger obstacle in speaking and writing respectively. It is evident that the problems are not significantly different. Although it is also true all of these problems are present in all student speaking and writing, for the sake of comparison we wanted the students to choose only the one that presents the greatest challenge. Table 3: Comparison between the main problems students encounter in speaking and writing. Problem Speaking Writing I lack ideas/content 10.8 % 15.4 % I lack vocabulary to express ideas I have 16.9 % 15.4 % I can get my ideas across but not very clearly 27.7 % 27.7 % I have the vocabulary but I lack structures 44.6 % 41.5 % Source: own research Finally, it is also worth noting which of the nine specific skills studied as part of the English of Tourism course the students see as more important, and at which they consider themselves to be better. For easier comparison and clarity the results are presented in Table 4 and the means are given as a score. Number one was assigned for the most important or the best at and number nine for the least important or the worst at. Therefore, the lower the mean the more important the skill (in case of the first column), or the better they are at it (in case of the second column). The number in the brackets indicates the relative order within the same column. Table 4: Students' perceived importance of the four skills and own perception of own proficiency. skill important I am good at making and delivering a presentation 5,2500 (6) 3,6491 (2) writing a report 4,7656 (5) 5,1053 (5) taking a telephone booking 3,8906 (1) 3,2456 (1) replying to a booking via e-mail 4,5938 (4) 3,9649 (3) reading a tourism related article in a newspaper or a specialised magazine / journal 6,3906 (9) 4,7018 (4) reading a contract in order to understand the agreed terms 4,4688 (3) 6,0000 (7) negotiating a contract on behalf of a tour operator 4,2344 (2) 6,3158 (8) writing a text for a brochure 5,4063 (7) 5,6842 (6) delivering a high quality tour guide's commentary 5,9375 (8) 6,4211(9) Source: own research Although the whole of Table 4 is interesting and each item deserves a close analysis we will point out only several figures of direct relevance for our study. The first thing that catches the eye is the first line where delivering a presentation is not considered very important - but the students do feel they are good at it. This information asks for further analysis because all Business English and English of Tourism language instructors would probably disagree with it. This is, however, in line with the students' perception of their proficiency in speaking in general. Another interesting point to make is the order of the first three skills the students feel they are good at: telephone bookings, presentations, and replying to a booking via e-mail. It is exactly these three skills that students have encountered in this course so far. Again, the confidence in choosing these as the first three might have been encouraged by a feeling of familiarity. Finally, we would particularly like to emphasize the skill of responding to bookings via e-mail, since it was the object of our final analysis. According to our students this is the fourth skill in order of importance and the third most developed. We will analyze this rather short piece of writing in order to check whether the students were realistic in their assessment and to indicate the major problems as a guideline for tackling this writing assignment with further generations of students of tourism. 4. 4. Written assignment analysis In the above-mentioned survey the students indicated writing as the most difficult language skill to become proficient at - the results show it is ranked far behind the other three major language skills. We have, however, also shown that the problems students encounter in both productive skills (speaking and writing) are similar and the perceived difference between the two is not as big as it may seem. In the 51 written assignments we have found many errors, all related to the four main problems indicated in the survey questionnaire: the lack of content, the lack of vocabulary, the lack of correct structures to incorporate the vocabulary in, and finally the feeling that the message has been conveyed but not very clearly. In order to both present the extent of the problem and to inform future teaching practice we have broken down the errors into the three main categories which are then further divided into subcategories. There is, of course, some overlapping, which is to say that some errors can fall under more than one category. It is, however, not our aim to draw a detailed map of errors but to either confirm or reject the students’ rather high perception of general proficiency in English and to either confirm or reject their rather poor perception of their writing skills. As shown in Figure 1 there are three main categories: structure, language, and style. inappropriately organised content no introductory information no closing grammar lexical grammar vocabulary syntax Style lack of paragraphs Language Structure Figure 1: Categories of errors in students' written assignments formal vs. informal written vs. spoken inappropriate content confusing content incorrect salutation lack of relevant information incorrect closing politeness As the main structural flaws we have noticed almost a complete lack of paragraphing (in 30 assignments) or inappropriately organized content (in 3 assignments). Twelve assignments lack introductory information, while nine of them lack a closing. We have also listed incorrect salutations and closings under this category although they could be also errors of lexical grammar, e.g. knowing what “dear” is followed by at the beginning of a formal letter or knowing what “looking forward” is followed by at the end of a letter. The latter could be considered syntactical, as well as a lexical grammatical error. We’ve selected several lines from the corpus of students’ assignments to illustrate the misusage of “dear” (Dear John Bean we accepted ...; Dear John, I'm happy …; Dear Sir Bean, we are …; Dear Sir John, ...) and “look/ing forward” (we look forward to see you...; we are looking forward seeing you...; hotel is looking forward to meet you). In the language category we have noticed a series of grammatical errors mainly regarding the wrong singular-plural agreement (in 8 assignments; e.g. all of your question…; room for two person…), wrong article (repeatedly in 25 assignments), wrong choice of tense (e.g. we will be having a few options for you), misuse of passive (e.g. I have been received your request…; how I been read), wrong verb form (e.g I sayed…; our hotel don’t have), wrong indirect questions (you can choose do you want a room with). An area more extensive and more complex, however, is that of lexical grammar. Many errors that would traditionally be classified as grammar are now seen as lexical grammar for the longer stretches of meaningful language items they form with other lexical elements. A typical functional word such as a preposition will depend on the word it is used with and may present a frequent source of confusion and errors. E.g. prepositions have been misused 11 out of 17 times after the noun “view,” a noun frequently occurring in LoT. Other errors of this type may include such lexical items that require to be followed by a definite verb form or type of sentence. E.g. I like you to inform about … is wrong because the verb like has its own rules about larger lexical structures into which it can fit. The lack of knowledge of how words combine to produce a desired meaning is what we refer to in the questionnaire item “I have the vocabulary but I lack structures.” 41.5% of students have identified this as an obstacle in their written production whereas a much lesser percentage (15.4%) think they lack the vocabulary itself. Our analysis has confirmed these results. Vocabulary problems have been noticed on two levels: semi-technical and general vocabulary while technical vocabulary was not to be expected in a short communication exchange such as a reply to an e-mail booking. Semi-technical vocabulary, which is used in general language but has a higher frequency of occurrence in specific descriptions and discussions (Dudley-Evans and St John, 1998:83) has been erroneously used in the following examples: all-inclusive room, full-pansion, aviable. Most errors, however, are made in the use of general vocabulary. The most evident is the wrong use of collocations caused in particular by mother tongue interference (e.g. we accepted your request; if you have additional questions; price is accessible; normal room you are interesting for our hotel). Next, a number of typical syntactic problems have been identified as well. Again, as it was the case with lexis and grammar it is very difficult to draw clear boundaries between syntactic errors and lexical grammar ones. If a verb is followed by a certain structure it is equally lexical grammar and syntax because it is that particular verb that will decide the final order of elements in the sentence. Another typical syntactic error is wrong word order such as: in price is included; there are available two types of rooms. Finally, the vast majority of the students used a register which is not appropriate when responding to a booking enquiry via e-mail. Such professional encounters require that conventional rules of politeness be observed. As part of the first encounter, an impolite or inappropriate response to a booking inquiry will likely put off a potential client. Even more, the higher the level of English the more serious politeness breaches appear (Camerer, 2012). Our linguistically competent but sociolinguistically immature students could have therefore committed many serious blunders by using informal or spoken style (e.g. You won't regret it!); as a result of alluding to taboo topics (e.g. I recommend a room for married couples with a jacuzzi and a big bed.), as they overwhelmed the guest with unnecessary or confusing information, or as they addressed the guest with arrogance (e.g. if you need more information, check our website!). It is therefore of paramount importance that future professionals fully understand the sociolinguistic requirements of their job, that they are aware of taboo topics and can express the correct level of politeness. 5. Conclusion In this paper we set out by proposing two myths regarding foreign languages as related to the tourism industry: 1) Croatian students are highly proficient speakers of English, and 2) Sufficient knowledge of general English is enough for working in the field of tourism. In response to the first myth the study has shown the following: Overall, first year students consider themselves sufficiently proficient in English. Even in a short professional piece of writing students show having problems at different linguistic and non-linguistic levels that we have identified, classified, and exemplified in the study. Students perceive speaking as their biggest strength and writing as their biggest weakness, the latter being in accordance with language professionals'/lecturers' view but the former not. The problems identified are only partially related to the specificities of EoT. They are more related to the general English language issues, thus the myth of having a student population of highly proficient speakers of English can be rejected. In response to the second myth and a series of specific goals that resulted from it we have shown that: Language of tourism is specific and should therefore be treated distinctively in language instruction at the institutions of higher education. Students are aware of the difference between GE and EoT only to an extent. Professional content does not contribute to the increase in tourism students' motivation to learn EoT. Although students see possible benefits of having EoT skills for increasing their employment competitiveness, they are still primarily interested in learning English as a lingua franca. There is a common agreement among BE teachers and business executives that excellent communication skills are requisites students need when they enter the business world and when they become members of the “discourse community” (Widdowson, H.G.,1998). The same can be said of EoT with an additional emphasis on the subtleties of its sociolinguistic features. Thus, it follows: EoT teachers and courses should be committed to raising students’ awareness of particular skills typical of the specialized language of tourism. Despite a rather high level of GE and the linguistic confidence students may have, those extra skills need to be added to the range of their language competencies. Sociolinguistic competence should be strongly emphasized. EoT courses should address the language related both to professional and academic skills in order to meet (1) the present need of the students to consult academic sources and produce academic texts in English, and (2) the future need to competently use English in their prospective tourism careers. Let future tourism professionals not forget that the first step toward their professional success will hinge on their ability to use the (English) language to lure, seduce, bring and conquer the evergrowing number of English speaking tourists. References Bagarić, V. (2007). English and German learners' level of communicative competence in writing and speaking, Metodika 8 (14): 235-257. Calvi, M. V. (2005). „El español del turismo: problemas didácticos‟. Ideas (FH-Heilbronn): 1. Available at http://ideas-heilbronn.org/artic.htm. Council of Europe (2001). Common European Framework of Reference. Cambridge; UK: Cambridge University Press. Camerer, R. (2012). Your politeness or my politeness? Matters in international encounters. BESIG-Conference Stuttgart, November 2012. Čepon, S. (2005). Business English in practical terms. Scripta Manent [online], 1 (1), 45-54. Dann, G. (1996). The language of tourism: a sociolinguistic perspective. UK: CAB International. Dann, G. (2003). Noticing notices: tourism to order. Annals of Tourism Research 30 (2): 465-484. Dann, G. (2012). Remodelling a changing language of tourism: from monologue to dialogue and trialogue. Pasos Vol. 10 No. 4. Special Issue, 59-70. Donna, S. (2000), Teach Business English. Cambridge University Press Europeans and their languages (2012). Special Eurobarometer 386. Dörnyei, Z. (2005). The psychology of the language learner. Individual differences in second language acquisition. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers. Dörnyei, Z., Csizér, K. and Németh, N. (2006). Motivation, Language Attitudes and Globalisation: A Hungarian perspective. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. Dudley‐Evans, T. and Jo St John, M. (1998). Developments in English for Specific Purposes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Gardner, R. C. (2010). Motivation and second-language acquisition. The socio-educational model. New York: Peter Lang. Gatehouse, K. (2001) ”Key Issues in ESP Curriculum Development”, The Internet TESL Journal, Vol. VII, No. 10, October 2001., http://iteslj.org/ Geld, R. and Stanojević M.-M. (2007). Reading comprehension: Statistical analysis of test results for primary and secondary schools. Metodika 8 (14): 137-147. Graddol, D. (2006). English next. The British Council. http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_386_sum_en.pdf International Journal of Multilingualism vol. 4 (4), 262-281. Jelovčić, I. (2008). English for Specific Purposes: Student Attitude Analysis. Metodika 20 (1/2010), str. 124-136. Josipović Smojver, V. (2007) Listening comprehension and Croatian learners of English as a foreign language. Metodika 8 (14): 137-147. Kabalin Borenić, V. (2010a) Teaching languages for specific purposes to students of non philological studies. Survey results. Presentation given at the Round table: Languages for Specific Purposes – 5 years of Bologna at the Faculty of Economics, University of Zagreb, December 3 rd 2010 Kabalin Borenić, V. (2010b). Should business students learn about EU language policy and the changing status of English. Paper presented at Language Teaching in Increasingly Multilingual Environments. Warsaw, September 16th – 18th 2010. Book of Abstracts (p 52). Ed: Michal Paradowski. Warsaw, Poland: Liber. Kabalin Borenić, V. (2013). Motivation and language learning in non philological study programmes. Unpublished PhD thesis. Klein, C. (2007). The valuation of plurilingual competences in an open European labour market. Lamb, M. (2004). Integrative motivation in a globalizing world. System, 32, 3-9. Laurence, A. A freeware concordance program for Windows, Macintosh OS X, and Linux., available at http://www.antlab.sci.waseda.ac.jp/software.html Mader, J. and Camerer, R. (2010). International English and the Training of Intercultural Communicative Competence. Interculture Journal 12, 97-116. Medved Krajnović, M. (2007). How well do Croatian learners speak English?. Metodika 8 (14): 182-189. Medved Krajnović, M. & Letica, S. (2009). Foreign language learning in Croatia: policy, science and the public. In: Granić, J. (ed.), Language policy and language reality. Zagreb: Croatian Association of Applied Linguistics. Mihaljević Djigunović, J. (1998). The role of affective factors in foreign language learning. Zagreb: Faculty of Phylosophy , University of Zagreb. Mihaljević Djigunović, J. (2007). Croatian EFL learners’ affective profile, aspirations and attitudes to English classes. Metodika 8, no. 14: 115-126. Mihaljević Djigunović, J. (in press). Multilingual attitudes and attitudes to multilingualism in Croatia. In Singleton, D., Fishman, J., Aronin, L. and Ó Laoire, M (eds) Current Multilingualism: a new linguistic dispensation. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. Mihaljević Djigunović, J. i Geld, R. (2002/2003). English in Croatia Today: Opportunities for Incidental Vocabulary Acquisition, SRAZ XLVII-XLVIII: 335-352. Nickerson, C. (2005). English as a lingua franca in international business contexts. English for Specific Purposes 24 (4), 367-380. Retreived from the web December 7, 2012. http://www.sdutsj.edus.si/ScriptaManent/2005_1/Cepon.html Retreived from the web January 27, 2013. Swales, J. (1990). Genre Analysis: English in Academic and Research Settings. Cambridge: Cambridge Applied Linguistics. Tribble, C., (1997), Improvising corpora for ELT: Quick and dirty ways of developing corpora for language teaching. U: Lewandowska- Tomaszcyk B. and Melia P.L. (eds)., Practical applications in language corpora. Lodz, Poland: University Press. accessed on November 5th 2006 at http://web.bham.ac.uk/johnstf/palc.htm Zergollern-Miletić, Lovorka (2007). Writing – the proficiency of Croatian students at the end of primary and secondary education. Metodika 8 (14): 205-220. Yashima, T. (2000). Orientations and motivation in foreign language learning: A study of Japanese college students. JACET Bulletin, 31, 121-134. Widdowson, H. G. (1998). Communication and Community: The pragmatics of ESP. English for specific purposes, vol. 17, 3-14.