Supporting Children*s Healthy Weight Module

advertisement

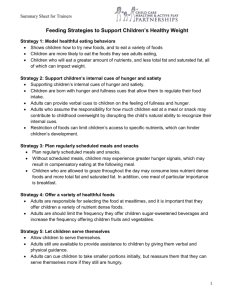

Background Information for Trainers Feeding Strategies to Support Children’s Healthy Weight Prevent Overweight and Support Healthy Weight Caregivers’ feeding strategies can impact children’s weight. For example, controlling or restricting feeding practices can lead to weight preoccupation (Fisher & Birch, 1999). Further, children’s exposure to an obesigenic food environment increases their desire and consumption for less nutrient dense foods (Briley, Roberts-Gray, & Simpson, 1994). Appropriate feeding strategies can be used to prevent overweight and support a healthy weight. Strategy 1: Model healthful eating behaviors Preventing overweight and supporting children’s healthy weight starts with adults modeling healthful eating behaviors as they eat with the children. When adults eat with children, they can show children how to try new foods, and to eat a variety of foods (see recommendations by the American Medical Association at the end of the background information). Modeling increases healthful eating behavior, because children are more likely to eat the foods they see adults eating, particularly nutrient dense foods (Moag-Stahlberg, 2003). Therefore, when adults eat foods of high nutritional value children are more likely to eat those same foods. The result of adults modeling healthful eating behaviors is children who will eat a greater amount of nutrients, and less total fat and saturated fat, all of which can impact weight. Strategy 2: Support children’s internal cues of hunger and satiety While adults are responsible for modeling healthful eating behaviors, they also are responsible for supporting children’s internal cues of hunger and satiety. 1 Background Information for Trainers As Satter (1987) describes in her Division of Responsibility, adults are responsible for what food is offered and the children decide how much or whether to eat the food. Children are born with hunger and fullness cues that allow them to regulate their food intake (Johnson, 2000). However, some children who are obese or overweight may need additional support in the development and recognition of their hunger and fullness cues. Adults can provide verbal cues to children on the feeling of fullness and hunger, such as phrases with children that will cue them to whether their stomach feels hungry or full (Ramsay, et al., 2010). Adults who assume the responsibility for how much children eat at a meal or snack may contribute to childhood overweight by disrupting the child’s natural ability to recognize their internal cues. When adults limit children’s food intake children can develop fears about food. These fears can result in children’s overconsumption of food, or specific foods, at another time (Fisher & Birch, 1999). Adults support children by offering a variety of nutrient dense foods for meals and snacks, and then children should be allowed to decide how much or whether they eat foods from what adults offer (Moag-Stahlberg, 2003). Further, restriction of foods can limit children’s access to specific nutrients, which can hinder children’s development. There are short term and long term consequences that occur when adults take over the child’s job of deciding how much to eat, even with a child who is overweight. When adults assume this responsibility, they are suggesting, “I don’t trust your cues.” In the long term the 2 Background Information for Trainers child is going to stop trusting their own cues because the adults have taken over their natural self-regulation. Strategy 3: Plan regularly scheduled meals and snacks Another strategy to prevent childhood overweight and support a healthy weight is to plan regularly scheduled meals and snacks. If adults fail to provide routines for meals, children’s ability to self-regulate caloric intake can be disrupted. Without scheduled meals, children may experience greater hunger signals, which may result in compensatory eating at the following meal. If this continues, children begin to eat out of fear of not having enough food rather than whether they are hungry or full, which will contribute to childhood overweight (Sigman-Grant, 2008). Encouraging regularly scheduled meals and snacks is important throughout the day. First, when meals are scheduled throughout the day there is less reliance on children grazing or eating foods at any time of the day. Children who are allowed to graze throughout the day may consume less nutrient dense foods and more total fat and saturated fat. In addition, one meal of particular importance is breakfast. Children who regularly consume breakfast are more likely to maintain a healthy weight (Rampersaud, Pereira, Girard, Adams & Metzl, 2005). Adults can reinforce the importance of eating breakfast, ensure children are offered breakfast on a regular basis, and create structured mealtimes at consistent times throughout the day. Strategy 4: Offer a variety of healthful foods 3 Background Information for Trainers As adults plan regularly scheduled meals and snacks, they must do their job of deciding what foods to offer children, the fourth strategy of feeding young children. Adults are responsible for selecting the food at mealtimes (Satter, 1987), and it is important that they offer children a variety of nutrient dense foods. Children should be offered a variety of nutrient dense foods that provide adequate vitamins, minerals and calories. As supported by the AMA, children should be offered foods that are rich in calcium and fiber; balanced in carbohydrate, protein, and fat; and limited in energy-dense foods is optimal. Also, adults are should limit the frequency they offer children sugar-sweetened beverages and increase the frequency offering children fruits and vegetables. By offering children these foods, adults are better supporting children’s consumption of those foods, which can result in a healthy weight. Strategy 5: Let children serve themselves The fifth strategy is allowing children to serve themselves. This strategy helps children self regulate their food intake. Adults still are available to provide assistance to children by giving them verbal and physical guidance. Adults can cue children to take smaller portions initially, but reassure them that they can serve themselves more if they still are hungry. In order to facilitate letting children serve themselves, adults must consider how the food is offered. With the increase in portion distortion in our society, children have been offered foods in portions that may be unsupportive of their natural ability to recognize hunger and fullness (Fisher, 2007). Adults may often forget how to offer foods to children that meet their physical and physiological 4 Background Information for Trainers development. Preventing overweight can be done by offering children smaller units of food, or “child sized servings,” which gives them a greater ability to physically manage the food. For example, rather than offering a child whole sandwiches or even half sandwiches, cut the sandwich into fourths can allow children to choose the amount that is more appropriate for them. When children are offered smaller units, adults are better supporting children’s fullness cues and to prevent overeating. For example, offering a child pizza in small “child serving size” slices, rather than the standard large pizza slices, allows them to select the amount they need to meet their hunger needs. Not only can adults facilitate smaller units of food, but they also can make sure children are given smaller serving utensils that discourage over-serving. As children are serving themselves, adult can assure the child that they can have more food if they are still hungry. Strategy 6: Supportive Environment The sixth feeding strategy is that adults must determine whether the environment during mealtimes supports children’s self regulation. A pleasant mealtime environment fosters children’s ability to self-regulate intake, encourages a variety of foods, and promotes communication and interaction between children and the adults. The way to ensure the mealtime environment is pleasant is accomplished by establishing a positive physical, auditory, and social environment. A television that is turned on, even if not in the room, during mealtimes can negatively impact the mealtime environment (Dennison, B.). Televisions can be 5 Background Information for Trainers distracting to the adult and children, and deter mealtime conversations and children’s interest in the food. Adults can create a social environment that gives children the opportunity to express themselves in a comfortable and safe environment. When children feel comfortable and safe at mealtimes they are more likely to want to continue the mealtime, share in the mealtime conversations, and try foods offered on the table. Adults who pressure or force a child to eat or to limit food create a negative mealtime environment. To encourage children to eat a variety of nutrient dense foods, mealtimes must be supportive and pleasant, which are supportive of a healthy weight. Strategy 7: Avoid rewarding or consoling with food When adults consistently reward and console children with food, they are creating a food habit that may last the child’s lifetime. Rewarding with food elevates the preference for that food. Further, rewarding and consoling with food along with other manipulative feeding strategies to persuade children to eat more, eat less, or to behave in a specific way, hinders children’s ability to self regulate intake of food. Better strategies are rewarding with a desired activity or giving the child extra time with the caregiver. The seven feeding strategies are guiding strategies for mealtimes with young children in group settings. Using these feeding strategies, adults can provide an optimal mealtime environment that is supportive of children’s healthy weight. These strategies are aimed so that adults can support children’s self-regulation of intake by cueing them to their feelings of hunger and fullness. Adults can 6 Background Information for Trainers encourage the consumption of a variety of foods by eating those foods with the children, talking about those foods, and helping children familiarize themselves with those foods. Adults should plan regularly scheduled meals and snacks, offer children a variety of nutritious foods, and adults should allow children to serve themselves. By using these appropriate feeding practices children’s health weight can be supported and children can develop a positive relationship with food that will last their lifetime. 1. Moag-Stahlberg, A., Miles, A., & Marcello, M. (2003). What kids say they do and what parents think kids are doing. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 11, 1541-1546. 2. Satter, E. (1987). How to get your kid to eat but not too much. Boulder, CO: Bull Publishing Company. 3. Johnson, S. L. (2000). Improving preschoolers’ self-regulation of energy intake. Pediatrics, 106, 1429-1435. 4. Sigman-Grant, M., Christiansen, E., Fernandez, G., Fletcher, J., Johnson, S.L., Branen, L.J., & Price, B. (2008). Hungry Mondays: Low-income children in child care. Hunger & Environmental Nutrition, 2, 19-38. 5. Fisher, J.O., Liu, Y., Birch, L.L., & Rolls, B.J. (2007). Effects of portion size and energy density on young children’s intake at a meal. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 86, 174-179. 6. Fisher, J.O. & Birch, L.L (1999). Restricting access to palatable foods affects children's behavioral response, food selection, and intake. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 69,1264–1272. 7. Dennison, B.A., Erb, T.A., & Jenkins, P.L. (2002). Television viewing and television in bedroom associated with overweight risk among low-income preschool children. Pediatrics, 109, 1028 – 1035. 8. Weight Relativities Division of the Society for Nutrition Education. (2003). Guidelines for childhood obesity prevention programs: Promoting healthy weight in children. Journal of the Nutrition Education and Behavior, 35, January-February. 9. Barlow, S.E., & Dietz, W. H. (1998). Obesity evaluation and treatment: Expert committee recommendations. Pediatrics, 102, 1-11. 10. Wardle, J., Carnell, S., Haworth, C. M. A, & Plomin, R. (2008). Evidence for a strong genetic influence on childhood adiposity despite the force of the obesogenic environment. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 87, 398-404. 11. Rampersaud, G. C., Pereira, M. A., Girard, B. L., Adams, J., & Metzl, J. D. (2005). Breakfast habits, nutritional status, body weight, and academic 7 Background Information for Trainers performance in children and adolescents. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 105, 743-760. 8 Background Information for Trainers AMA Expert Committee Prevention Recommendations for Physicians 1. Physicians and allied healthcare providers counsel the following: i. Dietary Intake: 1. Limiting consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and encouraging consumption of diets with recommended quantities of fruits and vegetables. ii. Physical Activity: 1. Limiting television and other screen time to 1 or 2 hours per day in children starting as young as age 5 years, as advised by the American Academy of Pediatrics and removing television and computer screens from children’s primary sleeping area. iii. Eating Behaviors: 1. Eating breakfast daily. 2. Limiting eating out at restaurants, particularly fast food restaurants. 3. Encouraging family meals in which parents and children eat together. 4. Limiting portion size. 2. Physicians, allied healthcare professionals, and professional organizations advocate for: a. The federal government to increase physical activity at school through intervention programs as early as grade 1 through the end of high school and college, and through creating school environments that support physical activity in general. b. Supporting efforts to preserve and enhance parks as areas for physical activity, informing local development initiatives regarding the inclusion of walking and bicycle paths, and promoting families’ use of local physical activity options by making information and suggestions about physical activity alternatives available. 3. Use the following techniques to aid physicians and allied healthcare providers who may wish to support obesity prevention in clinical, school, and community settings: a. Actively engaging families with parental obesity or maternal diabetes, because these children are at increased risk for developing obesity even if they currently have normal BMI. b. Encouraging an authoritative* parenting style in support of increased physical activity and reduced sedentary behavior, providing tangible and motivational support for children. c. Discouraging a restrictive† parenting style regarding child eating. d. Encouraging parents to model healthy diets and portion sizes, physical activity, and limited television e. Promoting physical activity at school and in child care settings (including after school programs 4. Children of healthy weight participate in 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity daily. i. The 60 minutes can be accumulated throughout the day, as opposed to only single or long bouts. ii. Ideally, such activity should be enjoyable to the child iii. Whereas some health and psychological benefits may be attained by achieving the 60 minute goal, greater duration should yield increased benefit 5. Suggests counseling patients and families to perform these behaviors: i. Dietary Intake: 1. Eating a diet rich in calcium 2. Eating a diet high in fiber 3. Eating a diet with balanced macronutrients (calories from fat, carbohydrate, and protein in proportions for age recommended by Dietary Reference Intakes) 4. Encouragement, support, and maintenance of breastfeeding ii. Eating Behaviors: 1. Limiting consumption of energy-dense foods. * Authoritative parents are both demanding and responsive. "They monitor and impart clear standards for their children’s conduct. They are assertive, but not intrusive and restrictive. Their disciplinary methods are supportive, rather than punitive. They want their children to be assertive as well as socially responsible, and self-regulated as well as cooperative" (Baumrind, 1991, p. 62). † Restrictive parenting (heavy monitoring and controlling of a child's behavior) 9