HomeWork 2 - WordPress.com

advertisement

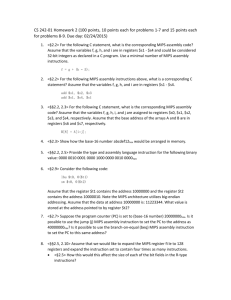

Exercise2.1 a.) f = g – h; b.) f = g + (h – 5); 2.1.1 For the C statements above, what is the corresponding MIPS assembly code? Use a minimal number of MIPS assembly instructions. a.) sub f, g, h # The sum of g and h is placed in f b.) subi f, h, 5 # Temporary variable f contains h – 5 addi f, f, g # the sum of f “(h-5)” and g in the place of f 2.1.2 For the C statements above, how many MIPS assembly instructions are needed to perform the C statement? For f = g – h; you would only need one subtraction, so only one MIPS assembly instruction is needed. But for f = g + (h – 5); there is one addition and one subtraction, so we’ll need two MIPS assembly instructions. 2.1.3 If the variables f, g, h, and i have values 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively, what is the end value of f? The end values of f are: f = g – h; —-> f = 2 – 3 ——> f = -1 f = g + (h – 5); ——-> f = 2 + ( 3 – 5) ——> f = 2 + (-2) —–> f = 0 even though there is a value for F to begin with, that doesn’t matter seeing as f is going to be over written. 2.1.4 For the MIPS assembly instructions below, what is a corresponding C statement? a.) addi f, f, 4 b.) add f, g, h add f, i, f a.) f = f + 4; b.) f = g + h; f = i + f; f = i + (g + h); // (g + h) is being stored in the value of f // the value of f from the first statement is being added to i and stored in f // same as the two before but is more readable 2.1.5 If the variables f, g, h, and i have values 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively, what is the end value of f? a.) f = f + 4; —-> f = 1 + 4 —> f = 5 b.) f = g + h; —–> f = 2 + 3 —-> f = 5 f = i + 5; ——> f = 4 + 5 —> f = 9 f = i + (g + h); —-> f = 4 + (2 + 3) —-> f = 4 + 5 —–> f = 9 Exercise 2.2 a.) f = g – f; b.) f = i + (h – 2); 2.2.1 For the C statements above, what is the corresponding MIPS assembly code? Use a minimal number of MIPS assembly instructions. a.) sub f, g, f # The sum of g and f is placed in f b.) subi f, h, 2 # Temporary varible f contains h – 2 add f, i, f # The sum of i and f is placed in f 2.2.2 For the C statements above, how many MIPS assembly instructions are needed to perform the C statement? For f = g – f; there is only one subtraction so that’s going to be only one MIPS assembly instruction. For f = i + (h – 2); there is one addition and one subtraction, so there is going to be two MIPS assembly instructions. 2.2.3 If the variables f, g, h, and i have values 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively, what is the end value of f? a.) f = g – f; —> f = 2 – 1 —> f = 1 b.) f = i + (h – 2); —> f = 4 + (3 – 2) —> f = 4 + 1 —> f = 5 2.2.4 For the MIPS assembly instructions below, what is a corresponding C statement? a.) addi f, f, 4 b.) add f, g, h sub f, i, f a.) f = f + 4; b.) f = g + h; // (g + h) is being stored in the value of f f = i – f; // the value of f from the first statement is being subtracted to i and stored in f f = i – (g + h); // same as the two before but is more readable 2.2.5 If the variables f, g, h, and i have values 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively, what is the end value of f? a.) f = f + 4; —-> f = 1 + 4 —> f = 5 b.) f = g + h; —> f = 2 + 3 —> f = 5 f= i – 5; —-> f = 4 – 5 —> f = -1 f = i – (g + h); —-> f = 4 – (2 + 3) —> f = 4 – 5 —> f = -1 Exercise 2.3 a.) f = -g – f; b.) f = g + (-f – 5); 2.3.1 For the C statements above, what is the corresponding MIPS assembly code? Use a minimal number of MIPS assembly instructions. a.) sub f, -g, f # The sum of -g and f is placed in f b.) subi f, -f, 5 # Temporary variable f contains -f – 5 add f, g, t0 # The sum of g and f is placed in f 2.3.2 For the C statements above, how many MIPS assembly instructions are needed to perform the C statement? For f = -g – f it’s just one subtraction so that will be only one MIPS assembly instruction. For f = g + (-f – 5) that is one addition and one subtraction, so you will need two MIPS assembly instructions. 2.3.3 If the variables f, g, h, i, and j have values 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively, what is the end value of f? a.) f = -g -f; —-> f = -2 – 1 —-> f = -3 b.) f = g + (-f – 5); —> f = 2 + (-1 – 5) —-> f = 2 + (-6) —> f = -4 2.3.4 For the MIPS statements below, what is a corresponding C statement? a.) addi f, f, -4 b.) add i, g, h add f, i, f a.) f = f + (-4); b.) i = g + h; // (g + h) is being stored in the value of i f = i + f; // the value of f from the first statement is being added to i and stored in f f = (g + h) + f; // same as the two before but is more readable 2.3.5 If the Variables f, g, h, and i have values 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively, what is the end value of f? a.) f = 1 + (-4); —–> f = -3 b.) i = g + h; —> i = 2 + 3 —> i = 5 f = i + f; —-> f = 5 + 1 —> f = 6 f = (g + h) + f; —-> f = (2 + 3) + 1 —> f = 5 + 1 —-> f = 6 Exercise 2.4 Assumptions: variables f, g, h, i, and j are assigned to registers $s0, $s1, $s2, $s3, and $s4, respectively. Base address of the arrays A and B are in registers $s6 and $s7, respectively. a.) f = -g – A[4]; b.) B[8] = A[i - j]; 2.4.1 For the C statements above, what is the corresponding MIPS assembly code? a.) lw $t0, 32($s6) # Temporary reg $t0 gets A[4] sub $s1, $zero, $s1 # Subtracting 0 – g to get -g, contained in $s1 sub $s0, $s1, $t0 # $s0(f) = $s1(-g) – $t0(A[4]) b.) sub $t0, $s3, $s4 # Temporary variable $t0 gets i –j, i is stored in $s3 and J is stored in $s4 lw $t1, $t0($s6) # Temporary variable $t1 gets A[i-j] sw $t1, 32($s7) # B[8] = A[i-j], Stores A[i-j] back into B[8] 2.4.2 For the C statements above, how many MIPS assembly instructions are needed to perform the C statement? For both a) and b) there are 3 MIPS assembly instructions where needed to perform the C statement. Because we have to perform a (lw) transfer to a register first and then we perform a (sw) transfer back to the memory. 2.4.3 For the C statements above, how many different registers are needed to carry out the C statement? For a) we used; $t0, $s6, $s1, $zero, $s0. Five different registers were need to carry out the C statement. For b) we used; $t0, $s3, $s4, $s1, $s6, $t1, $s7. Six different registers were needed to carry out the C statement. Excerise 2.6 Assumptions: variables f, g, h, i, and j are assigned to registers $s0, $s1, $s2, $s3, and $s4, respectively. Base address of the arrays A and B are in registers $s6 and $s7, respectively. a.) f = f + A[2]; b.) B[8] = A[i] + A[j]; 2.6.1 For the C statements above, what is the corresponding MIPS assembly code? a.) lw $s0, 4($s6) # Temporary reg $s0 gets A[2] sub $s0, $s0, $s1 #$s0(f) = $s0(A[2]) - $s1(f) add $s0, $s0, $s2 # $s0(f) = $s0(A[2]) + $s2(f) b.) add $t0, $s6, $s3 # $t0 = $s6(A[2]) + $s3(i) lw $t0,0($t0) # Temporary variable $t0 gets A[i] add $t1, $t0, $s7 #$t1 = $t0(A[i]) + $s7(A[j]) lw $s0, 4($t0) # B[8] = A[i] +A[j] 2.6.2 For the C statements above, how many MIPS assembly instructions are needed to perform the C statement? For a) there are 3 MIPS assembly instructions where needed to perform the C statement. For b) there are 4 MIPS assembly instructions where needed to perform the C statement. Because we have to perform a (lw) transfer to a register first and sub and add operations. 2.6.3 For the C statements above, how many different registers are needed to carry out the C statement? For a) we used; $s0, $s6, $s1, $s2. Four different registers were need to carry out the C statement. For b) we used; $t0, $t1, $s0, $s6, $s7. Five different registers were needed to carry out the C statement. Excerise 2.10 a.) 00000 0010 0001 0000 1000 0000 0010 0000_two b.) 0000 0001 0100 1011 0100 1000 0010 0010_two 2.10.1 For the binary entries above, what instruction do they represent? a.) 0000 0010 0001 0000 1000 0000 0010 0000 Name Format op rs rt rd shamt 0000 00 10 000 1 0000 1000 0 000 00 6 bits 5 bits 5 bits 5 bits 5 bits funct 10 0000 6 bits add 32 R 0 16 16 16 0 b.) Name Format sub R 0000 0001 01000 1011 0100 1000 0010 0010 op rs rt rd shamt 0000 00 01 010 00 101 1 0100 1000 0 6 bits 5 bits 5 bits 5 bits 5 bits funct 10 0010 6 bits 0 34 10 5 20 16 2.10.2 What type (I-type, R-type, J-type) instruction do the binary entries above represent? As you can see from the table in 2.10.1 the op code for both a. and b. is 0, therefore they represent the R-type of format. 2.10.3 If the binary entries above were data bits, what number wouuld they represent in hexadecimal? 32 16 8 4 2 1 a.) binary 0000 00 10 000 1 0000 1000 0 000 00 10 0000 deccimal 0 16 16 16 0 32 hexadecimal 0 10 10 10 0 20 0 1 16 + 4 + 2 + 1 = 23 0 1 1 1 b.) binary 0000 00 decimal 0 hexadecimal 0 01 010 10 A 00 101 5 5 1 0100 20 14 1000 0 16 10 10 0010 34 22 0 0 0 1 1 1 4+2+1=7 I labeled the top row 32, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1 then fill in the binary number below. If there is a 1 present you count it and if there is a 0 you don’t. Once you add them together you get the decimal conversion of the binary number. If the binary number is bigger than double the top row until you get the appropriate length. Excerise 2.11 a.) 0x01084020 b.) 0x02538822 2.11.1 What binary number does the above hexadecimal number represent? Using a hexadecimal converter I got a.) 1010 1110 0000 1011 1111 1111 1111 1100two b.) 1000 1101 0000 1000 1111 1111 1100 0000two 2.11.2 What decimal number does the above hexadecimal number represent? Using a hexadecimal converter I got a.) 2920022012 b.) 2366177216 2.11.3 What instruction does the above hexadecimal number represent? Using a hexadecimal converter I got a.) sw $t3, -4($s0) b.) lw $t0, -64($t0)