Promoting Critical Thinking through Cooperative Learning

advertisement

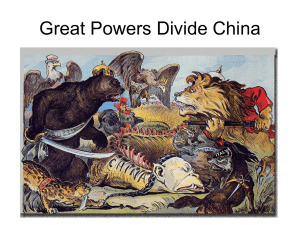

Supplemental Handouts for Promoting Critical Thinking through Cooperative Learning Title Slide Introduction to Barbara Cowboy boots: Texas White water rafting: Knee surgery May 25 Slide: Goals of this presentation Participants will: • Explore some of the theory behind learning and critical thinking; • Experience some active learning, student-centered techniques they can adapt for their own classes; • Reflect on the nature and process of learning; • Enjoy interacting with colleagues. Four Cartoons: stop and think, how birds see the world, fish’s fault, dogma bag Agenda • An Overview/Introduction, including a look at Critical Thinking • Snowball discussion: barriers to cooperative group work • A look at one cognitive development/teaching implication • Guided Reciprocal Peer Questioning (Question Shuffle or Guided Peer Discussion) • Send-a-Problem • Conclusion Slide: Critical thinking involves entering imaginatively into opposing points of view to create “dialogic exchange” between our own view and those whose thinking differs substantially from our own. —Richard Paul, cited in John C. Bean, Engaging Ideas Slide: Two Activities Central to Critical Thinking • Identifying and challenging assumptions, and • Exploring and imagining alternatives. —Stephen Broookfield Slide: In critical thinking all assumptions are open to question, divergent views are aggressively sought, and the inquiry is not biased in favor of a particular outcome. —Joanne Kurfiss Cartoon: Your problem is you see the world in black and white. Slide: Eight Teaching Principles that Support Critical Thinking Across the Curriculum Kurfiss, J. G. (1988) Critical Thinking: Theory, Research, Practice, and Possibilities. ASHEERIC Higher Education Report No. 2. Washington, DC: Associate for the Study of Higher Education Slide: 1. Critical thinking is a learnable skill; the instructor and peers are resources in developing critical thinking skills. Slide: 2. Problems, questions, or issues are the point of entry into the subject and the source of motivations for sustained inquiry. Cartoon: Elephant Hide Slide: 3. Successful courses balance challenges to think critically with support tailored to students’ developmental needs. Slide : 4. Courses are assignment centered rather than text-and-lecture centered. Goals, methods, and evaluation emphasize using content rather than acquiring it. Cartoon: Irrelevant Slide: 5. Students are required to formulate and justify their ideas in writing or other appropriate modes. Cartoon: Writer’s Block Slide: 6. Students collaborate to learn and to stretch their thinking, for example, in pair problem solving and small group work. Slide: 7. Several courses, particularly those that teach problem-solving skills, nurture students’ metacognitive abilities. Cartoon: I lift, you grab. Slide: 8. The developmental needs of students are acknowledged and used as information in the design of the course. Teachers in these courses make standards explicit and then help students learn how to achieve them. Slide: These eight principles can be promoted through structured group work: Cooperative Learning Slide: What is cooperative learning? Slide: Snowball Discussion Two people respond to the given question with as many ideas as they can generate They join another pair and share their ideas before generating additional ones together The four remain a team. Slide: What are the barriers to cooperative learning? Your own? Your students? Your chair’s? Your instituition’s? Slide: Spiral Curriculum Sequencing is important. Wiggins and McTighe, for example, use the term “the spiral curriculum.” Others speak of “scaffolding.” Wiggins, G. & McTighe, J. 1998. Understanding by Design. Alexandra, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. Slide: Helping Students Make Connections: The Importance of Previewing Material. Slide: Time for a Story If the balloon popped, the sound wouldn’t be able to carry, since everything would be too far away from the correct floor. A closed window would also prevent the sound from carrying, since most buildings tend to be well insulated. Since the whole operation depends on a steady flow of electricity, a break in the middle of the wire would also cause problems. Of course, the fellow could shout, but the human voice is not loud enough to carry that far. An additional problem is that a string could break on the instrument. Then there could be no accompaniment to the message. It is clear that the best situation would involve less distance. Then there would be fewer potential problems. With face to face contact, the less number of things could go wrong. From Bransford & Johnson (1973) Slide: Think-(Write)-Pair-Share How many ideas can you remember from the story? Students’ memories benefit from linking new information to things they already know. To be maximally effective, the context/schemas need to be activated BEFORE students receive ambiguous information Cartoon: One must think before one speaks Slide: • • • • Generic Question Stems What is the main idea of…? What if…? How does. . .affect…? What is the meaning of…? • • • • • • • • • • What is a new example of…? Explain why…? How does this relate to what I’ve learned before? What conclusions can I draw about…? What is the difference between A and B? How are A and B similar? How would I use A to B? What are the strengths and weaknesses of …? What is the best…and why? Explain how…? Question Shuffle: Preparation for a Midcourse, Final, or Short Answer Exam • Out-of-class: Each student reviews the material and writes on an index card two thoughtprovoking essay questions based on the generic question stems. • In-class: Students pair and select from their four questions the two most viable ones—the two that best synthesize the material and promote learning; they write these two questions on another index card. • The cards are passed around the room so that each pair receives a different card with two viable questions; they agree on the best question. • The teacher indicates a time period similar to the time available on the exam (20 minutes?) and each student individually writes a response to question selected with his or her partner. • When time is called, the two partners swap papers, read, and discuss their two answers. • Depending on the time available, the process is repeated. • The teacher collects all the papers and reviews them, using some questions on the actual exam and using the student responses as the starting point for a grading rubric. Slide: Guided Reciprocal Peer Questioning in groups of 4–5 each bring three or more “authentic” questions based on the stems. • A leader sees that every student has an opportunity to pose a question as long as they use different stems. • A recorder notes the question and captures the “gist” of each discussion. • When time is called (at least 30 minutes) the group reviews the recorder’s notes and selects their best question and discussion. • A spokesperson from each group summarizes this information for the class as a whole (Recorders’ notes—with the best question starred—can be submitted later for later distribution or for posting to a Web site.) • The individual questions are turned in to the instructor to ensure accountability. Slide: Send-a-Problem This structure is particularly effective for problem solving. Its exact source is unknown. The Howard County Maryland Staff Development Center developed a version of it inspired by Kagan's (1989) work. The starting point is a list of problems or issues, which can be generated by students through an activity such as a Roundtable or Snowball Discussion or can be teacher-selected. Each team identifies the particular problem or issue upon which they wish to focus initially and records their choice on the front of a folder or envelope. Each team selects a different problem. The teams then brainstorm effective solutions for these problems and write them down on a piece of paper. At a predetermined time, the ideas are placed in the folder or envelope and forwarded to another team. The members of the second team, without looking at the ideas already generated, compile their own list. This second set of ideas is forwarded to a third team which now looks at the suggestions provided from the other teams, adds its own, and then decides on the two most effective solutions. Alternatively, the teams can come up with a synthesis of the ideas from all three teams. Besides encouraging collaborative higher order thinking skills, this structure results in student evaluative judgments, the highest cognitive level in Bloom's well-known taxonomy. Reports to the whole group occur as time permits and can take many forms, including written reports when the material is relatively complex. Some faculty members use this structure for examination review sessions by putting typical exam questions in folders for group problem solving. Instructions: Select one of the barriers you identified earlier through the snowball discussion and write it down on the post-it-note on your folder in question form (i.e, How can we prevent freeloading?) On a sheet of paper brainstorm all the solutions to the problem and when time is called, place it in your folder. Pass the folder—closed—to the group with the next highest number. When you receive a new folder, look at the problem/question on the post-it note and answer it on a separate sheet of paper, which will be placed in the folder and passed. Slide: Bloom’s Taxonomy: Evaluation, Synthesis, Analysis, Application, Comprehension, Knowledge Slide: Higher Order Thinking Higher-order thinking (HOT) requires students to manipulate information and ideas in ways that transform their meaning and implications, such as when students combine facts and ideas in order to synthesize, generalize, explain, hypothesize, or arrive at some conclusion or interpretation. Manipulating information and ideas through these processes allows students to solve problems and discover new (for them) meanings and understandings. —F. M. Newmann and G. G. Wehlage Slide: Parker Palmer Knowing and learning are communal acts. They require a continual cycle of discussion, disagreement, and consensus over what has been and what it all means. Cartoons: Stop and think, turn negative thoughts around, brain aerobics, galloping. Trichinosis be damned Slide: The End