here - John Cabot University

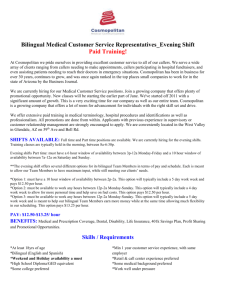

advertisement

Cosmopolitanism and Conflict John Cabot University, Rome, October 11-13 2013 PLENARY SESSIONS Mass Democracy and Republicanism without States James Bohman (St. Louis) My paper explores two interrelated features of modern political organization, both of which have consequences for current practices. The first is an understanding of democracy that I call self-legislation, the act of self constitution of the public as the subject and authors of the laws. I argue that this most common conception of modern political life has lost much its progressive character in light of fundamental changes in processes of self determination. The second set of concepts may offer a way to address the weaknesses of self legislation, based on an argument based in deliberative systems theory. This possibility is based on the emergence of transnational mass publics. One consequence of such mass publics is that they raise the level of contestation and conflict in the international system. Plenary sessions 1 Re-reading Hannah Arendt’s On Revolution with Cosmopolitan Intent Robert Fine (Warwick) Arendt’s On Revolution is not a cosmopolitan text, but it seems to me that, read as a phenomenology of experience and not as a purely normative political theory, there is much to be learnt from it for our vision and understanding of our what Arendt called our 'cosmopolitan existence'. I shall argue that On Revolution is best understood not as a statement of Arendt's own political opinions, but rather as an analysis of the developmental forms of consciousness that constitute the modern revolutionary tradition. In every case we have to deal with the gulf between the modern concept of revolution (as novelty and freedom) and the experience of conflict. It is in this context that I shall approach the further development of revolutionary consciousness, beyond the text itself, in relation to contemporary struggles for a cosmopolitan outlook. Crime and Punishment in a Cosmopolitan Society: The Effectiveness of Emergent International Criminal Justice Daniele Archibugi (Birkbeck and CNR, Rome) The paper tries to identify some key principles that distinguish cosmopolitanism from other approaches in terms of individual responsibility in international affairs. Many of these principles, and most notably the idea that a political community is not responsible for the wrongdoings of its rulers, have been absorbed by international law and practice. After the end of WWII, these principles have been codified in important documents, such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Nuremberg Principles. After the end of the Cold War, a further crucial development has emerged and the international community has started to be more active in pursuing investigations against egregious criminals, through a variety of national and international courts. Plenary sessions 2 But we are still far from a proper cosmopolitan criminal accountability. International hearings have put at the bar the weak players of world politics, rather than the strong. This confirms the realist prediction that the legal infrastructure is likely to reinforce the actual distribution of power, rather than counter-balance it. Moreover, the disproportion between the scale of international crimes, on the one hand, and number of individuals at the bar, on the other hand, undermines the legitimacy of individual criminal justice. This paper explores the following possible integrations to the current judicial system for international crimes following basic cosmopolitan principles. (1) The International Criminal Court should fully implement its mandate, by also being able to cover the crime most likely to be committed by strong world political players, namely, aggression. (2) The ICC should also be empowered to investigate crimes committed by powerful players. (3) The noble tradition of Opinion Tribunals, inaugurated by Bertrand Russell, Jean-Paul Sartre and Lelio Basso with the Tribunal for War Crimes in Vietnam, should become a core aspect of a cosmopolitan criminal justice, since it is more likely to target the powerful and the winners than the powerless and the losers. Even if Opinion Tribunals are not in a position to inflict punishment, they can vindicate the reasons of the weak players. (4) While the cosmopolitan idea that key culprits should be held criminally responsible still holds, there is the risk of exonerating collective responsibility through a few scapegoats. Some fresh forms of addressing major crimes through collective sanctions need to be explored to make a genuine reconciliation possible. (5) Finally, the potential of truth and reconciliation commissions, on the model pioneered by South Africa, should be further developed as a method to integrate individual criminal responsibility. Plenary sessions 3 Kant, Conflict, and Colonialism Pauline Kleingeld (Groningen) Kant is widely regarded as a fierce critic of colonialism. In Toward Perpetual Peace and The Metaphysics of Morals, for example, he forcefully condemns European conduct in the colonies as a flagrant violation of the principles of right. However, his earlier views on colonialism have not yet received much detailed scrutiny. In this essay I argue that Kant actually endorsed and justified European colonialism until the early 1790s. I show that his initial endorsement and his subsequent criticism of colonialism are closely related to his changing views on race, because his endorsement of a racial hierarchy plays a crucial role in his justification of European colonialism. He gave up both while he was developing his legal and political philosophy during the mid 1790s, and adopted a more egalitarian version of the cosmopolitan relationship among peoples. In the final section I address the question of whether Kant’s mature cosmopolitan ideal is the ideal of a future without conflict. Plenary sessions 4 Camus’s Rebellious Cosmopolitanism: Contradictions, Conflicts, and Limits of the Cosmopolitan Disposition Patrick Hayden (St. Andrews) Albert Camus’s existential thinking has been the object of renewed interest over the past decade. Political theorists have looked to his work to shed light on the contradictions and violence of modernity and the dynamics of postcolonial justice. This paper contends that Camus’s account of the modern human condition provides a means of engaging critically with one of the most compelling ideas linked to thinking about global politics today: cosmopolitanism. By developing Camus’s position on absurdity and rebellion, it suggests that the idea of cosmopolitanism should be situated in a post-foundationalist and post-teleological nexus to prevent it becoming a new political ideology of immutable truth. In order to make this argument, the paper focuses on how Camus’s thinking supports a rebellious cosmopolitan disposition towards global transformations, exclusions, and injustices. In so doing, it shows that cosmopolitanism must adopt an oppositional stance against the injustices of a deeply divided world, yet at the same time accept theoretical, factual, and moral limits on its vision and actions. Plenary sessions 5 PANEL SESSIONS A Responsibility for the Symptom or the Cause? Jus ante Bellum and Reevaluating the Cosmopolitan Approach to Humanitarian Intervention Garrett Brown (Sheffield) and Alexandra Bohm (Sheffield) Cosmopolitans often argue that the international community has a humanitarian responsibility to militarily intervene in order to protect vulnerable individuals from violent threats and to pursue the establishment of a condition of cosmopolitan justice based on the notion of a ‘global rule of law’. The purpose of this paper is to argue that many of these cosmopolitan claims are incomplete and untenable on cosmopolitan grounds because they ignore the systemic and chronic structural factors that underwrite the root causes of these humanitarian threats. By way of examining cosmopolitan arguments for humanitarian military intervention and how systemic problems are further ignored in the Responsibility to Protect (RtP), this paper suggests that many contemporary cosmopolitan arguments are guilty of focusing too narrowly on justifying a responsibility to respond to the symptoms of crisis versus demanding a similarly robust justification for a responsibility to alleviate persistent structural causes. Although this paper recognizes that immediate principles of humanitarian intervention will at times be necessary, the paper seeks to draw attention to what we are calling principles of Jus ante Bellum (right before war) and to stress that current cosmopolitan arguments about humanitarian intervention will remain insufficient without the incorporation of robust principles of distributive global justice which can provide secure foundations for a more thoroughgoing cosmopolitan condition of public right. Panel sessions 6 A Cosmopolitan Approach to Military Intervention: Reintroducing Natural Disaster Scenarios Lauren Traczykowski (Birmingham) In this paper I argue that individuals affected by natural disaster, in comparison with those affected by humanitarian emergencies or war, are equally deserving of international assistance. However, military intervention for natural disasters is often discounted because such responses are considered the obligation of national authorities who would consent to such an intervention when required. As I will discuss, these points do not always hold. I therefore argue for the expansion of analysis of cosmopolitan military intervention beyond humanitarian response to include intervention in natural disasters. My argument contains two central claims. First, I argue that humanitarian intervention and natural disaster response are operationally and ethically similar, and therefore a cosmopolitan approach to a military intervention for natural disaster is justified and necessary. Second, and relatedly, I argue that a cosmopolitan approach to military intervention in natural disaster response will enhance policymaking for all types of military intervention and allow for an improved and deep acceptance of a cosmopolitan perspective into both global post-conflict and natural disaster policymaking. Further, I demonstrate that the goal of a cosmopolitan humanitarian military intervention (assisting affected individuals), the issues arising during a military intervention (leadership vacuums, adherence to international conventions, and further atrocities), as well as justifications for intervention (just cause, and last resort) can be directly compared to a military intervention with a cosmopolitan ethic for a natural disaster. After offering this theoretical comparison, I consider a real-world example, the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, to further support my argument. I thus show that by reintroducing natural disasters into a cosmopolitan approach to military intervention, we can allow for more robust post-conflict operations, as well as increase the number of lives saved following a natural disaster. Panel sessions 7 How Cosmopolitanism Reduces Conflict: Narrow and Broad Readings of Kant's Third Ingredient for Peace Luigi Caranti (Catania/CNR, Rome) In the last three decades Kant’s cosmopolitanism has come to be recognized, well beyond the limited circle of philosophers, as a powerful and effective instrument to reduce militarized interstate conflicts. However, in the hands of political scientists, cosmopolitan right has been read narrowly, as nothing more than a precondition for economic interdependence. The third ingredient of Kant’s recipe for peace has thus become a reiteration of the tenet ‒ commonplace among liberal thinkers before and after Kant ‒ that international trade promotes peace (Doyle 1983a, 2005, Russett and Oneal 2001, Garztke, 2007). This paper argues that this amounts to a rather gross conflation between genus and species. The content of cosmopolitan right extends beyond economic interdependence, to cultural exchange and the construction of a global conscience modeled on the ‘natural rights of man’. Moreover, even the narrow reading is questionable. For it tends to conceive of economic interdependence independently of justice, which makes the theory vulnerable to the circumstances under which international trade may cause conflict rather than peace (Mearsheimer 1992, Uchitel 1993, Pogge 2008). This is surprising if one considers that Kant defends the pacific potential of trade in the same context in which he severely criticizes ‘the commercial states’ and their ‘trading companies’ (the multinationals of his time) for the injustice of their business affairs. The paper concludes by proposing a wider reading of cosmopolitan right intended to express its full potential for peace. Panel sessions 8 Contestatory Cosmopolitan Citizenship Kostas Koukouzelis (Crete) Moral cosmopolitanism sees cosmopolitanism’s core idea the equal moral value of every human being. Taken in this sense, it is doubtful whether, as a notion, cosmopolitanism adds anything to moral universalism as such. Political cosmopolitanism sees cosmopolitanism’s basic idea as human being’s having a certain (political) status, that is, certain capabilities, which normatively correspond to a certain kind of freedom. This paper’s argument argues that such a freedom should be conceived as non-domination and involves the power of contestation, an intrinsic element of modern republican citizenship in a democratic regime which should also be part of cosmopolitan citizenship. The first part of the paper will argue that enjoying freedom as non-domination involves having the power to contest laws and policies on an equal footing with others. This is part of the editorial dimension of democracy, which complements the authorial one. The former has to do with equal voice and power as antipower, while the latter has to do with voting. Contestation is exercised in the name of a universal value, that of nondomination, a value that points to inclusion and equal membership and should be exercised in a non-violent way. In the second part, I will attempt to argue that republican contestation refers to what Arendt has named the ‘right to have rights’. Now, in my view, the ‘right to have rights’ points precisely towards cosmopolitan citizenship, because it transcends the domestic, particularistic bias of the political. Such an approach is (a) both normatively robust, since it is based on universal non-domination, and (b) politically feasible, because it involves global institutional structures that enhance the editorial dimension of democracy, or contestation. In contrast, presupposing a collective subject through global legislation that is authorial or electoral democratization at a global level would be both unfeasible and undesirable. Under (a), the claim is that the ‘right to have rights’ has a redistributional aspect. Under (b), the claim is that contestatory cosmopolitan citizenship provides the necessary presuppositions for challenging national sovereignty, and therefore is both desirable and feasible – against to recent attempts (such as David Miller’s) to show that it is not. Panel sessions 9 Conceptualizing Cosmopolitan Solidarity Spela Mocnik (Sussex) In light of contemporary economic crises, a hardening of ethno-religious conflicts and peoples’ suffering, as well as confrontations of global ideologies, cosmopolitan theories of global politics need to move away from one-sided, idealizing presuppositions about rights, legal frames, rationality, and social relations. To respond to this challenge and rethink the constructive role of conflict or violence in shaping cosmopolitan theories, this paper proposes a turn to the idea of cosmopolitan solidarity, which is still undertheorized in the existing literature on cosmopolitanism. Cosmopolitan solidarity rethinks ethical life in the global sphere from the viewpoint not merely of abstract ideas such as justice or peace, but also of ideas of building on the vision of a society that is bound together by a commitment to opposing exploitation and suffering. It takes conflict and suffering as its points of departure, but is not submerged by them and remains committed to cosmopolitan ideas and action. This paper addresses the conceptualization of cosmopolitan solidarity. In the first part, I briefly look at the general account of cosmopolitan solidarity and outline its connection to the political. In the second part, I suggest that the conceptualization of cosmopolitan solidarity should stem from and be committed to constructing and upholding a common world. In the third part, I show that cosmopolitan solidarity does not have to be understood only as an enlargement of our moral imagination or in terms of being encompassed in the institutional structures; it can also be constructed from below, through ties of mutuality in the work of public and political practice. Panel sessions 10 Kantian Theory, Nuclear Weapons, and the Ethics of Coercive Anti-Proliferation Antonio Franceschet (Calgary) This paper examines the ethics of permitting and coercively limiting the possession of nuclear weapons by sovereign states. I argue that Immanuel Kant’s (1724-1804) political theory contains important resources in this regard, because it incorporates and surpasses the strengths of rival ethical approaches to nuclear weapons such as Realpolitik, the Just War Tradition, and Deontological Pacifism. Kant’s theory contains a strong presumption against the use of force. However, I also show how coercive anti-proliferation measures are morally legitimated by three possible justifications within Kantian theory. First, international justice necessarily allows for coercion against genuinely aggressive states engaged in nuclear aspiration. Second, Kant anticipates the need for centralized supra-state authority to guarantee a just form of anti-proliferation. Third, he advocates a cosmopolitan justification for sharing the earth’s surface, one that provides a distinctive and timely rationale for anti-proliferation policies in an era of globalization. Panel sessions 11 The Cosmopolitan Condition, Discourse Ethics, and Migrant Women: Rethinking Constitutional Patriotism Kanchana Mahadevan (Mumbai) ‘A political civic identity, without which Europe cannot acquire the capacity to act independently, can only evolve within a transnational public space.’ (Habermas) For more than a decade, Jürgen Habermas has diagnosed the conflict, or what he terms the ‘state of nature’, between nation-states as the outcome of abandoning international law against war. As a remedy, he proposes Immanuel Kant’s cosmopolitan condition, with its vision of peace in an interconnected world and responsibility to individuals. However, claiming that Kant’s world republic proposal falls into the trap of authoritarianism, Habermas argues for an international law based on deliberative democracy, discerning Kant’s core vision in international law that proscribes war and guarantees civic freedoms to individuals in transnational domains. Accordingly, the law itself – at local, national and transnational levels – is an ongoing project of public deliberation. For Habermas, such validation and institutionalization can take place through the transnational mobilization of local and national public spheres by media and non-governmental organizations. He argues that, rather than shared history, politics and culture, such publics be bound through constitutional patriotism. Yet Habermas’ juridical emphasis becomes suspect in an era characterized by increasing vulnerabilities of migrancy, which are mostly borne by women who confront structural obstacles at the levels of economic production and cultural reproduction. This paper examines Habermas’ reconstruction of Kant’s cosmopolitanism as constitutional patriotism. It argues that despite its strengths of decentering administrative and governmental authority, it remains rooted in the national public and the law. Moreover, constitutional patriotism’s ruptured links to discourse ethics make it immune and even antithetical to some of the challenges confronting migrant women. In conclusion, the paper addresses alternative, less legalistic ways of engaging with the spirit of Kant’s cosmopolitan principles from migrant women’s perspectives. Panel sessions 12 Theorizing Cosmopolitanism and Conflict: Beyond Sovereignty and Global Constitutionalism? Lars Rensmann (John Cabot) The paper problematizes several major schools of thought addressing problems of cosmopolitanism and (international) conflict. First, through the lens of Adorno, the paper offers a critique of both sovereign particularism, inspired by Hegel, and formal legal cosmopolitanism, inspired by Kant and reformulated in Habermas’s global constitutionalism. The former seeks to shield national power and conflict from transnational interferences, while the latter resort – albeit with qualifications – to formal legal principles lacking democratic checks. Both models are ill-equipped to deal with actual conflicts, crises, and crimes against humanity. Second, the paper discusses Adorno’s and Arendt’s non-formalistic cosmopolitan responses to humanitarian crises and conflicts. Notwithstanding substantive contradictions and conceptual shortcomings, turning to these theorists may lead to a more productive discussion of cosmopolitanism and conflict, moving the conversation beyond the dichotomy between democratic sovereigntism and cosmopolitan constitutionalism. Panel sessions 13 From Moral Equality to Political Equality: Making Radical Democracy Work in a Multipolar Pluriverse Helen Lindberg (Linneaus) This paper considers the similarities and differences between James Madison’s aggregative democracy, or federative republicanism, and Chantal Mouffe’s agonist radical democracy, focusing mainly on their assumptions of moral and political equality. The notion of universal political equality is fundamental to any liberal or cosmopolitan democratic theory. Madison’s fear of the concentration of power can be understood as a fear of hegemonic power. Faction for Madison was to be understood as a number of citizens, whether a majority or minority, who are united by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, and adverse to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community. I argue that radical democracy can be understood as a prudential and justificatory strategy for defending democracy, and that this affects the fundamental importance of the Dahlsian ‘principle of strong equality’. Dissolving the democratic paradox in the agonist way presupposes a political realist view on self or groupdetermination, to such an extent that democracy based on a necessary moral equality with its strong moral commitment to participatory and deliberating cooperation becomes unfeasible. I further argue that in a radical democratic and politically realist non-ideal theory of democracy, the relation between moral equality and political equality, and thereby also the basic possibilities for an egalitarian democratic decision making, gets unbalanced and evaded. I also address the question of the possibility of adapting Madison’s federal republicanism and Mouffe’s radical democracy to the international arena, and still maintain a cosmopolitan notion of democratic political equality as the basic value. I conclude that both a multipolar pluriverse based on an equilibrium between communities and a pluralist federal world arrangement will eventually lead to weakened equal standing between individuals within the plurality of communities or subunits, and thus a weakening of basic democratic values such as political equality that should be at the core of the constitutional essentials and political grammar of a cosmopolitan and egalitarian international arena. Panel sessions 14 Enemies, Adversaries and ‘Embedded Cosmopolitanism’: Considering Enmity in Contemporary and Modern Political Philosophy Daniela Ringkamp (Paderborn) Against the background of different cosmopolitan and communitarian visions of international relations, my paper focuses on the universalistic and particularistic premises of those discussions by considering some selected examples for each approach. My aim is to point to the conflictual dimension of even some universalistic, cosmopolitan accounts, which is often disregarded in contemporary debates, and to the concepts of enmity involved in them. The positions I will consider are Immanuel Kant’s construction of the league of peace as alliance between states, Chantal Mouffe’s concept of agonistic politics, and Toni Erskine’s vision of embedded cosmopolitanism. By comparing these approaches, I would like to outline a mediating vision of international relations, based especially on embedded principles as a particularistic starting point for integrative, cosmopolitan debates. Kant’s Toward Perpetual Peace is usually analyzed with a view to its universalistic, cosmopolitan aspects, such as its idea about world citizenship and the league of peace as an institutional framework for preventing war and enabling peace within international political relations. My interpretation, however, focuses on some inconsistencies of Perpetual Peace and its ambiguous descriptions of the league of peace. As the league of peace is exemplified as a negative surrogate of a world republic, the states involved regard each other as adversaries with different aims and interests, which are articulated within the league of peace, but which can also lead to its breakdown. Kant’s concept can be related to Chantal Mouffe’s considerations about international politics as an agonistic struggle between different opponents. By concurrently referring to and criticizing Carl Schmitt’s distinction between friend and enemy, Mouffe establishes a position which accepts the conflictual dimension of politics as a struggle between different opponents – between ‘us’ and ‘them’ – but which is able to construct the friend-enemy relation in a different way. For Mouffe, it is important to construct a mode of conflict which Panel sessions 15 provides space for divergent aspects and opinions without finding a consensus, but which also establishes a common ground between the opponents to prevent a violent outburst of the conflict. Kant’s and especially Mouffe’s approaches pave the way for a significant alternative theory, that of embedded cosmopolitanism established by Toni Erskine in an analysis of universal cosmopolitan and particular communitarian visions of international relations. Even Erskine’s account is based on the particularity of communities and a concept of adversary. However, by referring to common concepts of identity between the members of different communities, Erskine marks a starting point for the extension of one’s moral sphere of responsibility and of one’s identification with foreigners and adversaries. As embedded cosmopolitanism provides a realistic perspective on political relations and is oriented on an integrative, inclusive perspective, I conclude with the proposal to strengthen embedded cosmopolitanism as an adequate theoretical background for considering international relations. Panel sessions 16 The Institutional Implications of Agonistic Politics: From a Multipolar World Order to a Global Federal Union? Ronald Tinnevelt (Radboud) Chantal Mouffe originally developed her theory of agonistic politics to properly understand ‘the nature of a specific political regime: liberal pluralist democracy’ (2009:552). But she does not deny that some of the insights of her theory are also useful for understanding how the dimension of the ‘political’ can be acknowledged and incorporated into an agonistic model for Europe, or even a form of agonistic world order. What kind of institutions should be established on these levels to adequately foster a political forum in which agonistic practices can flourish, and how would these differ from currently existing institutions? How can the potential antagonism that exists in European and international politics ‘be played out in an agonistic way’ (2005:21)? What, in short, are the precise institutional implications of Mouffe’s theory of agonism for European and international relations? Unfortunately, Mouffe has not been very attentive to these specific questions. Although she opts for a European federal union and a multipolar world order in several of her articles, her main focus is on criticizing the normative presuppositions of the dominant cosmopolitan democratic model of theorists like Jürgen Habermas, David Held, and Daniele Archibugi. This paper, therefore, tries to critically reconstruct the extension of Mouffe’s theory of ‘agonistic pluralism’ to the European and international level, and argue that its institutional implications are not all that different from the cosmopolitan theoretical model she vehemently criticizes. In particular, it will be shown that, properly understood, agonistic pluralism leads to a form of global federal union, instead of a multipolar world order. Panel sessions 17 Cosmopolitan Adversaries: Exploring the Cosmopolitan Potential of Chantal Mouffe’s Adversarial Model Tamara Caraus (Bucharest) Agonistic theories of politics assume the permanence of conflict, disagreement, and contestation, and apparently are incompatible with cosmopolitanism considered as a vision of peace, looking for what unites humankind rather than divides it. Nevertheless, the purpose of this paper is to examine the potential for a theory of cosmopolitanism in the agonistic thinking of conflict and contestation. The focus will be on Chantal Mouffe’s position, which resolutely negates every ingredient necessary for a cosmopolitan theory. Her agonism postulates an ineradicable political antagonism, refers to groups and collectivities articulated through an ‘us-them’ distinction, and assumes ‘contingent foundations’ and traditions, while the core idea shared by all cosmopolitan views is that all human beings belong to a single community and the ultimate units of moral concern are individual human beings, not state or particular forms of human associations. However, the disambiguation of Mouffe’s theses makes room for a possible cosmopolitan adversarial agonism. In the first section of the paper, I provide a brief sketch of Mouffe’s adversarial agonism and of her account of a multipolar world, pointing to contradictions and inconsistencies of this model. In the second section, four elements from Mouffe’s adversarial agonism are examined, showing their cosmopolitan potential. Firstly, I will argue that Mouffe’s account of pluralism cannot be consigned to the ‘people’ and to the Western tradition, and that it allows for seeing the interconnectedness of political practices at different levels beyond ‘the people’. Secondly, the transformation from enemy to adversary through ‘conversion’ presumes a subject undergoing transformation endowed with moral and rational abilities and committing himself to a way of action which is more acceptable for others, a transformation which can also qualify as a ‘conversion’ to cosmopolitanism. Thirdly, I will argue that such notions of Mouffe’s as ‘shared symbolic space’, ‘conflictual consensus’, and the ‘common bond of adversaries’ are adequate for a cosmopolitanism that could avoid a global consensus, but will be based nevertheless on a minimal commonality of all human Panel sessions 18 beings. Finally, I will argue that contestation, as conflict in the ‘tamed’ mode, is a cosmopolitan possibility to contest hegemony wherever it is manifested in the world. In conclusion, I elaborate on the similarities and differences between agonistic cosmopolitanism and the standard sense of cosmopolitanism, emphasizing the plausibility and advantages of agonistic cosmopolitanism. Panel sessions 19 Kant and R2P Jennifer Ang (SIM, Singapore) Since the 1990s, there has been a rise in the number and magnitude of conscience-shocking humanitarian crises, and after several failed humanitarian interventions, the norms of international law shifted when the World Summit endorsed the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) document in 2005. Under the R2P, genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing, and crimes against humanity were formally identified as threats to international peace and security. Such human catastrophes were thus considered not only to allow, but also to demand a response. In fact, a growing number of governments have been shaping their foreign policies with R2P in mind, and we are now presented with an urgent need to clarify the notion of ‘responsibility’, especially in light of developments in Syria. Existing work by scholars such as Gareth Evans, Edward Luck, Alex Bellamy, and Thomas Weiss has established R2P as a duty to others based on human rights arguments, and offers us details as to what these responsibilities entail and their legal permissibility. Political and moral philosophers such as Tan Kok-Chor, Carla Bagnoli, Jennifer Welsh, and Miranda Banda have taken a reflective look into the nature and scope of our responsibility to protect, which is of specific interest to this paper. I urge a re-evaluation of the basis and nature of the duty to others using Kantian ethics in The Metaphysics of Morals, and aim to address the extent of its moral obligations. Further, I explain why we are morally required to rescue others even though we should not impose formal obligations, so as to maintain the moral significant of these duties and, hence, also the moral merit of those who choose to make this their duty. Panel sessions 20 Cosmopolitanism and Jus Soli: A Lesson Drawn from Lord Shaftesbury Angela Taraborrelli (La Sapienza, Rome) In an age of massive transnational migration, there is an undeniable tension between an international system of human rights, perhaps entailing the right of first admittance and just membership (including citizenship), and the authority claimed by nation states to control and sometimes restrain the flow of migrants. This paper suggests a theoretical basis which could be useful in dealing with this tension. I start by discussing the limits of the principles of jus sanguinis and jus soli in deciding who has the right to citizenship. Since, for example, the conscious will of the individual is not taken into account, it is suggested that neither principle can be consistent with a cosmopolitan view of citizenship. I go on to suggest that in Lord Shaftesbury’s search for a way to reconcile cosmopolitanism and patriotism into a coherent vision resources can be found for reconciling the tension between claims to citizenship and claims of the state. This is through a reinterpretation of jus soli such that the right of the immigrant to choose to seek citizenship is acknowledged and, at the same time, the cohesion of the original community is supported by a requirement that the immigrant has had a continued residence within the community and also has a stake in the continuity and democratic government of that community. A Brief Sketch of the Possibility of a Hegelian Cosmopolitanism David Rose (Newcastle) This paper is an attempt to investigate the possibility of a different account of cosmopolitan thought inspired by Hegelian considerations of Kant’s ethical theory. I contend that cosmopolitanism requires the objective freedom of a common shared humanity grounded in rational self-determination and that Hegel’s outline of the state in the Philosophy of Right can be extrapolated (contrary to Hegel’s own intuitions) to describe such a global community. Panel sessions 21 Toward a Constructive Conception of Human Rights Sine Bagatur (Rotterdam) Two approaches are often perceived to be dominant in the philosophical literature on human rights: the traditional/naturalistic/natural law conception and the practical/political conception of human rights. The traditional conception of ‘human rights as natural rights’ embraces the most common and well-known definition of human rights as those rights individuals have in virtue of being human. According to this conception, human rights are derived from some basic feature of human beings which are intrinsically valuable and essential, and recognized as such universally. Scholars with a naturalistic view of human rights propose various conceptions of humanity and fundamental goods as the source of human rights, such as the agency conception of humanity (Gewirth 1982, Griffin 2008), the conception of basic interests (Finnis 1980), or the idea of human dignity and freedom (Hart 1955). In recent debates, an alternative to the naturalistic view of human rights and their ethical justifications has been developed. Called the political/institutional (Cohen 2008) or practical approach (Beitz 2009), this starts from a functional account of the discursive practices of international human rights and stresses the political-legal aspect of human rights. Most versions of the political view adopt Rawls’s formulation of the main role human rights play in international legal and political practice, which is ‘to provide a suitable definition of, and limits on, a government’s internal sovereignty’ (Rawls 1999, p. 27) or ‘to restrict the justifying reasons for war and its conduct’ (Rawls 1999, p. 79). In this paper, I will argue for a constructive conception of human rights, taking my inspiration from Rainer Forst (1999, 2010). Firstly, I will examine the two main strands of thought on human rights and mention the core claims of each conception, briefly examining some theories of human rights associated with each strand and pointing to their problematic aspects. I will argue that naturalistic theories do not incorporate or make use of considerations about the political character or discursive functions of human rights within the existing practice. Moreover, they provide a primarily ethical justification of human rights, such that they focus on the Panel sessions 22 importance of human interests (associated with a notion of good life) they are meant to protect. Unlike naturalistic views, practical views regard human rights as having a primarily political and legal international status, but they leave their moral justification open. Using Forst’s constructive conception of human rights as a point of reference, I will argue that this approach is more plausible and has some advantages over other accounts. It pays attention to the two-tieredness of moral and political constructivism of rights: rights are constructed both as general moral rights and concrete legal rights. Moreover, human rights are seen as the result of the intersubjective, discursive construction of rights claims that cannot be reciprocally and generally denied between persons who respect one another’s right to justification. Finally, I will argue that this new political conceptualization of human rights embraces the social and historical aspects of human rights as ‘struggle concepts’ with a specific reference and examination of the case of ‘the right to housing’ struggles. Panel sessions 23 Conflicts of Citizenship: The Right to be a Non-Citizen with Political Rights Melina Duarte (Tromsø) A non-citizen is a resident-alien, a temporary resident, a refugee, an irregular immigrant, a stateless person, and a visitor; it is a person who lives in a country holding rights, a passport, and a deep root else/nowhere. Many of the non-citizens are, in fact, citizens elsewhere: Turks living in Germany, for example, are mostly (still) non-citizens in Germany, but they are citizens in Turkey. Others are simply citizens nowhere: the Rohingyas living in Myanmar, the Nubians living in Kenya, and the Bidoon living in Kuwait. In both cases of exclusionary citizenship, a citizenship in the country where they live is not granted in order not to endanger the alleged unity of the actual citizens. Indeed, Turks are culturally and ethnically different from Germans, as are the Burmese from the Royingya, the Kevans from the Nubians, and the Kuwaiti from the Bidoon. The ethnic differences are not going to be considered, since we have learned from our times that ethnicity per se should not be a condition for the distribution of any privilege or adversity. Setting the ethnicity aside, it seems that one solution to the limit or lack of rights of non-citizens would be the promotion of their full cultural integration into their hosting country. However, under the perspective of our contemporary liberal states, it would be unreasonable to forge a multicultural and pluralistic society by homogenizing its differences. My solution will rather be concerned with the enablement of different groups and persons to follow their own conception of good life, where they have the right to change what was once determined to them, as well as to review their choices, and, most importantly, where they can exercise their right to mobility and selfgovernance. Due to the loaded conception of citizenship, I will use the term in a very specific way: citizenship is a type of membership which requires the fulfilment of some conditions as well as of the external attestation from the group already formed. It means that it is not enough to a person to declare herself a citizen of one country; the group must also accept her claim to belong. Certainly this acceptation cannot be arbitrary and the conditions for claiming citizenship must be transparent, but the person seeking citizenship must observe them. However, non-citizens must be able not to need to completely integrate and assimilate the new culture, Panel sessions 24 abdicating their former personal attachments, in order to acquire rights in the hosting country. That is why I advocate for the right to the non-citizens to keep their foreigner citizenship or their stateless condition (if they wish) and still share the same rights as the citizens. I will argue that, although citizenship can somehow be restrictive, national membership should be a question of individual choice, rather than a prerogative of the nation-states or of any other external condition. Panel sessions 25