Chapter 32: Burns - Paramedic.EMSzone.com

advertisement

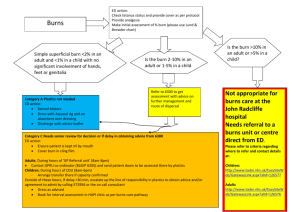

Chapter 32: Ready for Review Although you probably will not see moderate or severe burns on a daily basis, you will encounter some serious burn injuries during your career. The skin has four functions: to protect the underlying t issue from injury and exposure, to regulate temperature, to prevent excessive loss of water from the body, and to act as a sense organ. Burns are diffuse soft-tissue injuries created from destructive energy transferred via thermal, electrical, or radiation energy. Significant burn damage to the skin may make the body vulnerable to bacterial invasion, temperature instability, and major disturbances of fluid balance resulting in burn shock. Thermal burns include flame, scald, contact, steam, and flash burns. Beyond the visible soft-tissue injury, burns can affect the cardiovascular, respiratory, renal, gastrointestinal, hematological, and endocrine systems. The most important systemic response to significant burn trauma is burn shock. When burn shock occurs, capillaries leak out of the circulation into the interstitial spaces. Cells take in increased amounts of salt and water from the fluid around them. As with other types of shock, the body’s ability to distribute oxygen and glucose is hampered. Adequate fluid resuscitation is essential treatment. Burn wounds of the skin may be superficial, partial thickness, or full thickness. A superficial burn involves only the epidermis, and skin appears red and swollen. A partial-thickness burn involves the epidermis and part of the dermis. Moderate partialthickness burns usually are blistered, red, and extremely painful. Deep partial-thickness burns damage the hair follicle and sweat and sebaceous glands. A full-thickness burn involves destruction of the epidermis, the dermis, and the basement membrane of the dermis. After this type of burn, skin will not regenerate. Such a burn may appear white and waxy, brown and leathery, or charred. Inhalation burns may cause rapid airway compromise via heat and/or toxic chemicals entering the airway and lungs. Signs of irritation include coughing, wheezing, and possible stridor, signifying airway swelling. Carbon monoxide intoxication is also a concern. Establishing scene safety should be your first priority in responding to a burn call. Significant threats are likely to remain at the scene of a fire, chemical spill, electrical burn incident, lightning strike, or radiation leak. The many types of burns, coupled with the many possible presentations of burn patients, can challenge your assessment skills. Address a burned patient in a consistent, efficient, and systematic manner so you do not develop tunnel vision for the major burn trauma and miss other occult injuries that could affect the patient’s outcome. Once ABCs are addressed, assess the total body surface area (TBSA) burned, using the rule of palms, rule of nines, or Lund and Browder chart. This is an important step because burn severity relates to the need for transport to a burn unit. Most practitioners advocate counting only the areas of partial- and full-thickness burns (ignoring the areas of superficial burns). Remember that when using the rule of nines, different rules apply for infants, children, and the elderly. Three cornerstones of the emergency medical care of burns are airway management, with the potential need for field intubation, fluid resuscitation to prevent shock, and pain management. Cooling and sterile bandaging are indicated for certain thermal burns. Chemical burns of the skin or eyes generally require copious flushing with water, with certain exceptions. Many burn patients will ultimately require intubation, even if during their initial presentation they were able to talk to you. Patients who are in cardiac or respiratory arrest, or whose airways are rapidly swelling, will need field intubation. A deteriorating airway may or may not require field intubation. A patient whose airway is currently patent but who has a history consistent with risk factors for airway compromise may or may not need field intubation. Patients with more than 20% body surface area burns will need fluid resuscitation. It is important to give the correct amount of fluid; too much fluid may be as bad as too little. If fluid resuscitation is delayed more than 2 hours from the time of the burn in severely burned patients, resuscitation is complicated and mortality increases. Deliver an appropriate amount of fluid to the burn patient as soon as is reasonable. The Consensus formula is an equation used to determine the amount of fluid a burned patient will need during the first 24 hours. Note that only a small portion of this time will occur in the prehospital environment. Half of the amount must be given during the first 8 hours. The remainder is given over the remaining 16 hours. Remember to assess the patient’s pain and provide aggressive pain management. Pain medication is best given intravenously. Burn patients may require higher than usual doses of pain medications to achieve relief. Reassess the patient’s pain every 5 minutes. Chemical burns may affect the skin, eyes, or airway. Alkali burns are especially devastating. Typical management for removal of chemical solutions from the skin is copious flushing with water; management of powders requires brushing off as much of the substance as possible before washing. Management of chemicals from the eye involves flushing the eyes with copious amounts of water, and possibly removing contact lenses. Consider use of a Morgan lens. In cases of electrical burn, electric current is converted to heat as it travels through the body, causing extensive damage. Electrical burns generally leave two wounds, an entrance wound and a much larger exit wound. Assessment of electrical injuries first includes scene safety considerations, then beginning CPR if indicated. Management includes treating life-threatening injuries and potential shock. Most radiation burns are caused by gamma radiation, or x-rays. Assessment includes scene safety concerns. Management involves decontamination, irrigation, washing, possibly antidote administration, and transport. Pediatric patients can be more easily harmed by thermal injuries than other patients, and fluid resuscitation may be more challenging. Children may require dextrose- containing solutions earlier than adults; perform blood glucose monitoring routinely in seriously ill children. Pay careful attention to mechanism of injury; burns may raise the suspicion of child abuse. Elderly patients are also particularly sensitive to respiratory insults. They may have poor glycogen stores; check their blood glucose levels for hypoglycemia. Perform cardiac monitoring. Watch for pulmonary edema if performing fluid resuscitation.