Inequality, Discrimination and Social Cohesion

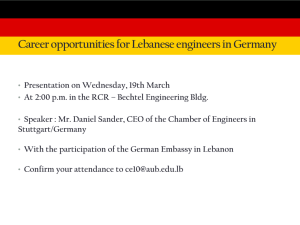

advertisement